The sun is in overdrive. For the first time in 2026, Earth’s star has unleashed its most powerful weapon: an X-class solar flare whose radiation rippled across the planet at light speed.

Scientists expected Solar Cycle 25 to begin winding down by now, yet the flares keep intensifying. NOAA monitoring stations detected activity patterns that haven’t aligned this dramatically since the early 2000s.

What triggered this violent outburst? And why is it arriving when forecasters thought the worst had passed?

Cycle 25’s Surprise

Solar Cycle 25, which began in December 2019, was predicted to be the weakest cycle in two centuries. Instead, it’s delivering record radiation storms and earth-directed coronal mass ejections at an alarming pace.

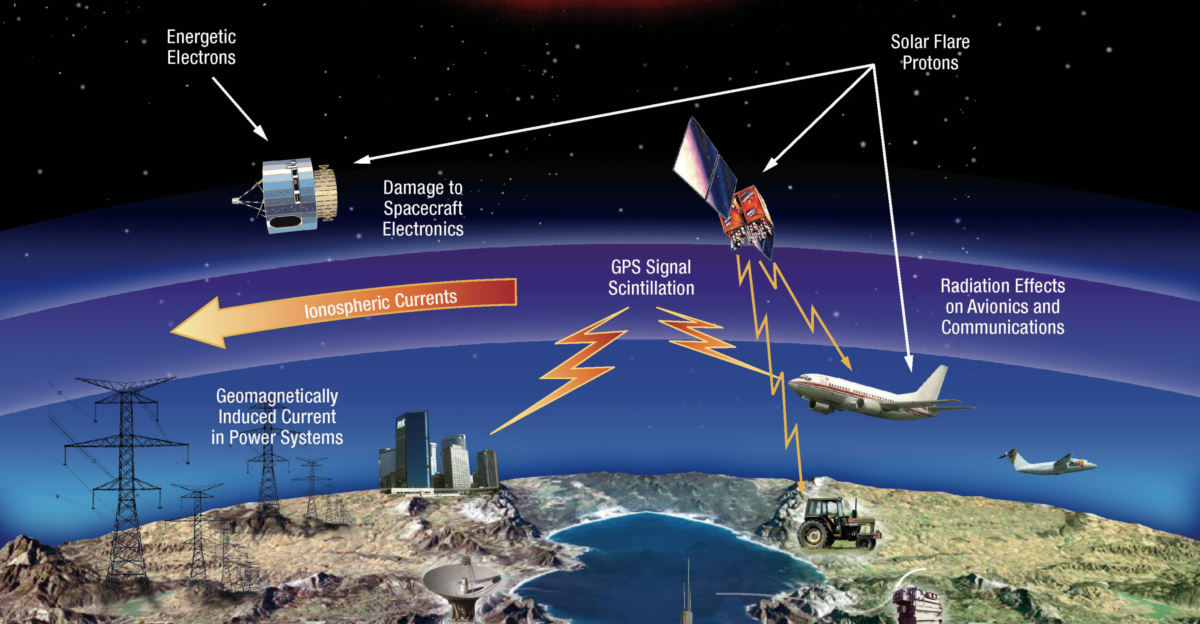

The first S4-level solar radiation storm in over 20 years struck on January 19, affecting satellites, aviation, and GPS systems globally. Scientists are scrambling to revise their forecasting models.

The shift forces a critical question: if our cycle predictions are this wrong, what else have we underestimated about the sun’s next decade of activity?

Why X-Class Matters

The NOAA Space Weather Scale classifies solar flares by intensity: A, B, C, M, and X. X-class flares are the most violent category—billions of times more energetic than nuclear weapons.

Each letter jump multiplies power tenfold; an X1.9 flare is 19 times more potent than an X1.0.

In human terms: X-class eruptions can black out radio communications across entire hemispheres within minutes and ionize the atmosphere so severely that airline pilots lose HF radio contact mid-ocean. The last comparable event hit in December 2025; before that, years separated major X-flares.

The Pressure Builds

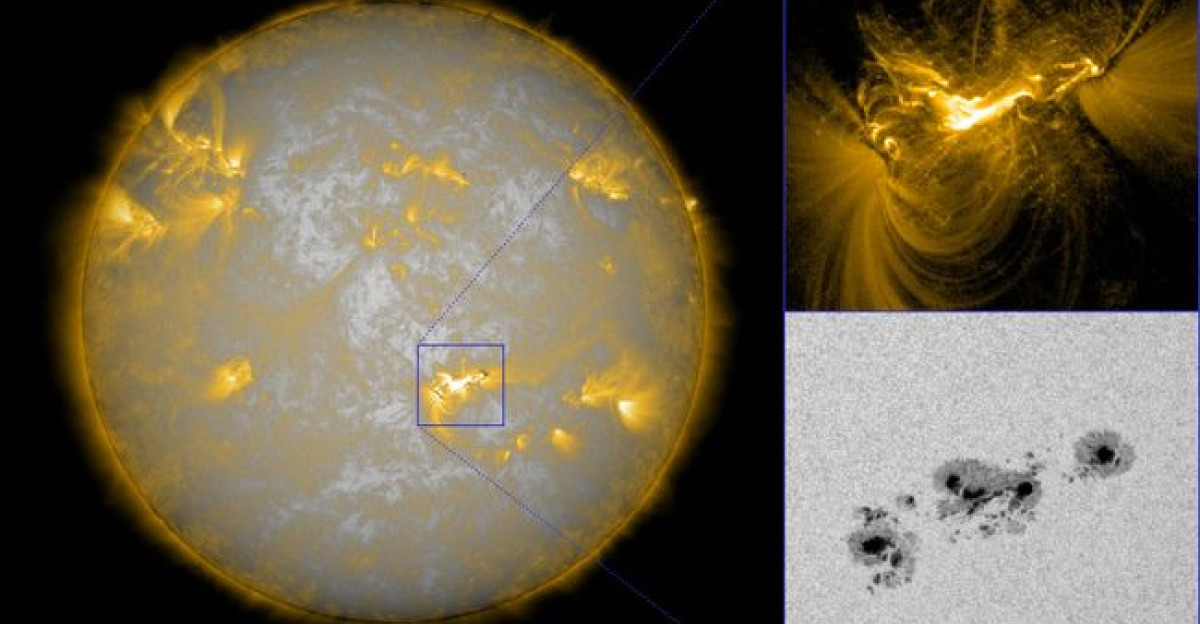

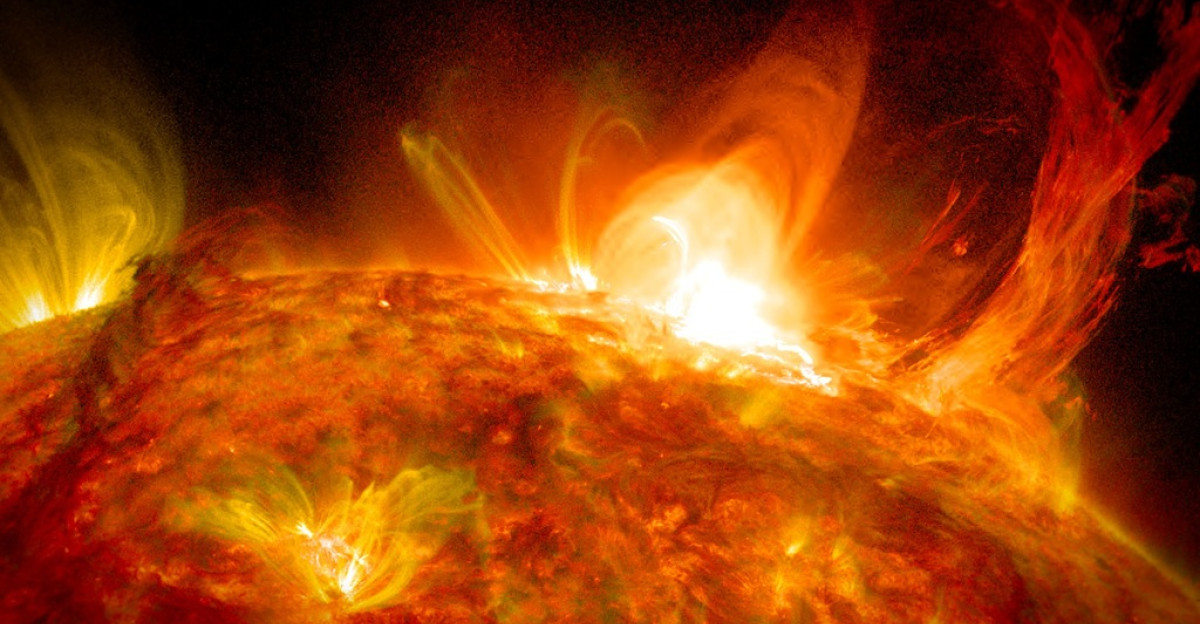

Active Region 4341, the sunspot cluster responsible for January’s eruptions, has grown increasingly unstable over the past three days. Before January 18, it produced several M-class flares—strong but not extreme.

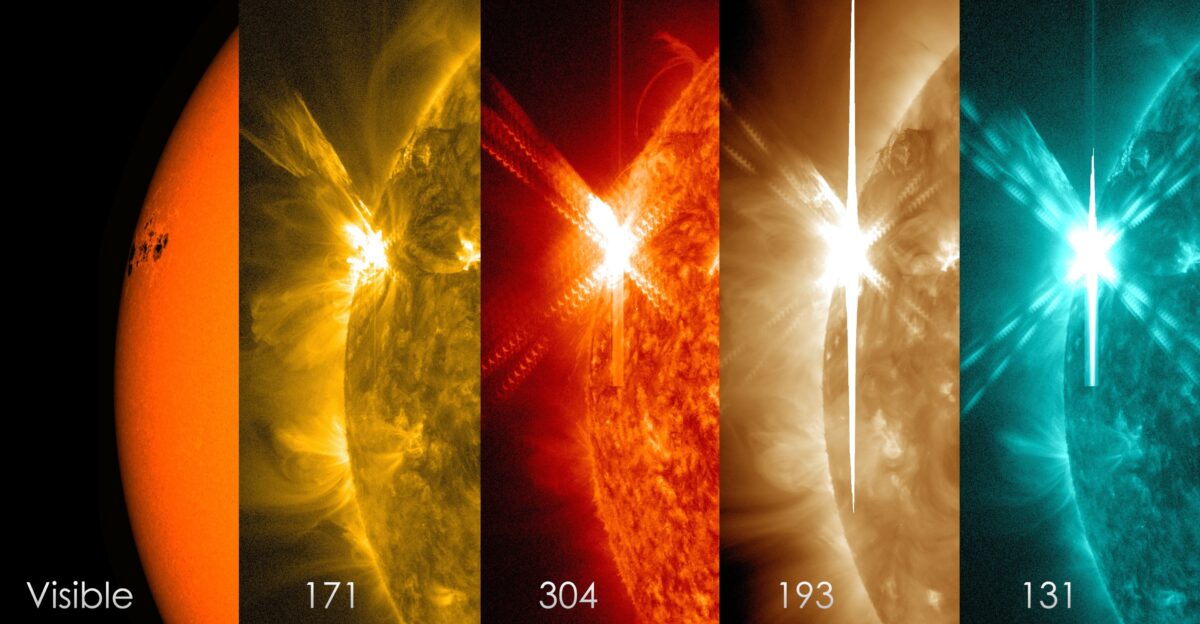

Each successive burst stretched the magnetic field tighter, storing more energy like a spring being compressed. X-ray imagery from NOAA’s GOES satellites showed the classic pre-flare signature: rapid flux growth and opposing magnetic polarities packed into a compact region.

By 18:09 UTC on January 18, the system snapped. The rupture was instantaneous and total—and nothing could prepare Earth for what came next.

The Flare Hits

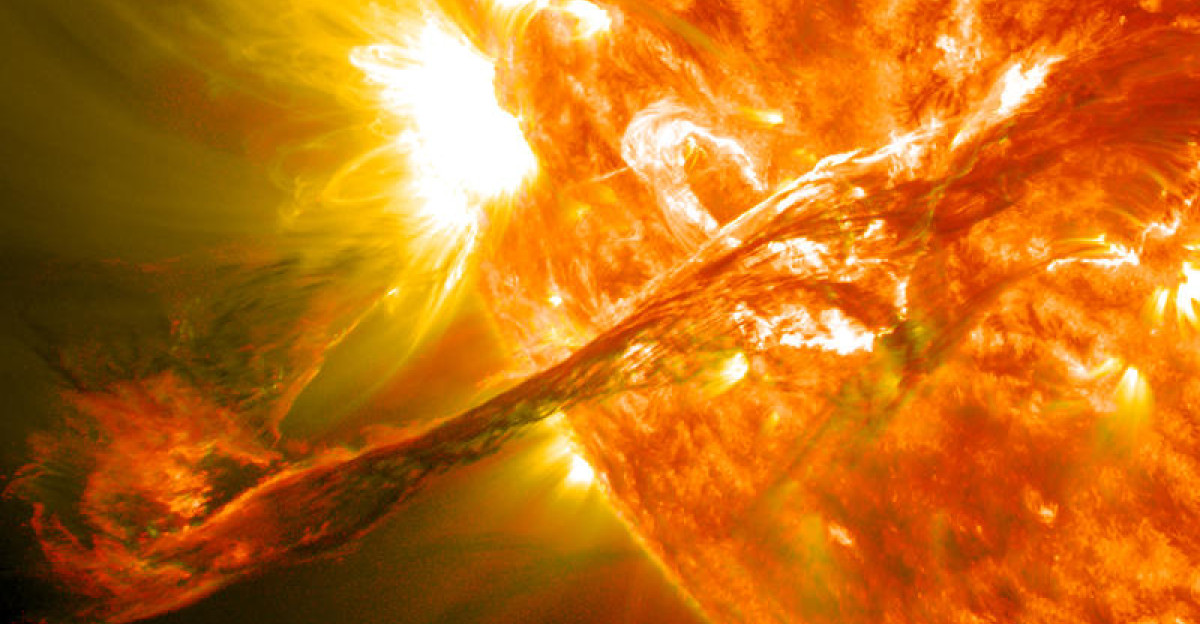

At 18:09 UTC on January 18, 2026, Active Region 4341 detonated with an X1.9/3b-class solar flare—the strongest and first X-class eruption of 2026. The explosion released energy equivalent to thousands of nuclear bombs, accelerating electrons and protons to near-light speed.

Within seconds, X-rays and ultraviolet radiation ionized Earth’s upper atmosphere over the sunlit hemisphere, particularly the Americas. Ground-based radio monitoring confirmed an R3-Strong (Strong) radio blackout lasting over one hour.

Shortwave radio frequencies below 10 MHz became useless for aviation, maritime, and emergency communications. The blackout affected Western South America, the eastern South Pacific, and parts of North America—an area measuring millions of square kilometers.

Americas in Darkness

Pilots crossing the Atlantic reported abrupt loss of HF radio contact during the one-hour blackout window. Commercial airlines operating Trans-Atlantic routes—some carrying hundreds of passengers—had to revert to satellite communications and VHF shortwave backup systems.

Maritime operators in the South Atlantic and Pacific reported similar outages, losing navigation updates and distress-signal capability temporarily. Ground-based shortwave networks in Brazil, Peru, and Mexico fell silent.

Emergency responders in the affected regions faced communications gaps during routine operations. While backup systems prevented catastrophic failures, the incident highlighted how dependent modern infrastructure is on radio propagation that the sun can disable in moments.

Cascading GPS Failures

Simultaneously, the solar radiation storm degraded GPS accuracy across North America and South America. Precision agriculture systems lost centimeter-level positioning and had to fall back to meter-level accuracy.

Financial trading floors in New York, Toronto, and São Paulo experienced microsecond-level timing jitters in their network clocks—not enough to trigger circuit breakers but enough to unsettle high-frequency traders. Surveying crews working on infrastructure projects in Mexico and Colombia abandoned fieldwork, unable to rely on positioning data.

Cell phone location services became less reliable. Most users never noticed, but critical sectors felt the pinch. The cumulative effect was a brief but real economic drag measured in millions of dollars across the continent.

The CME Launches

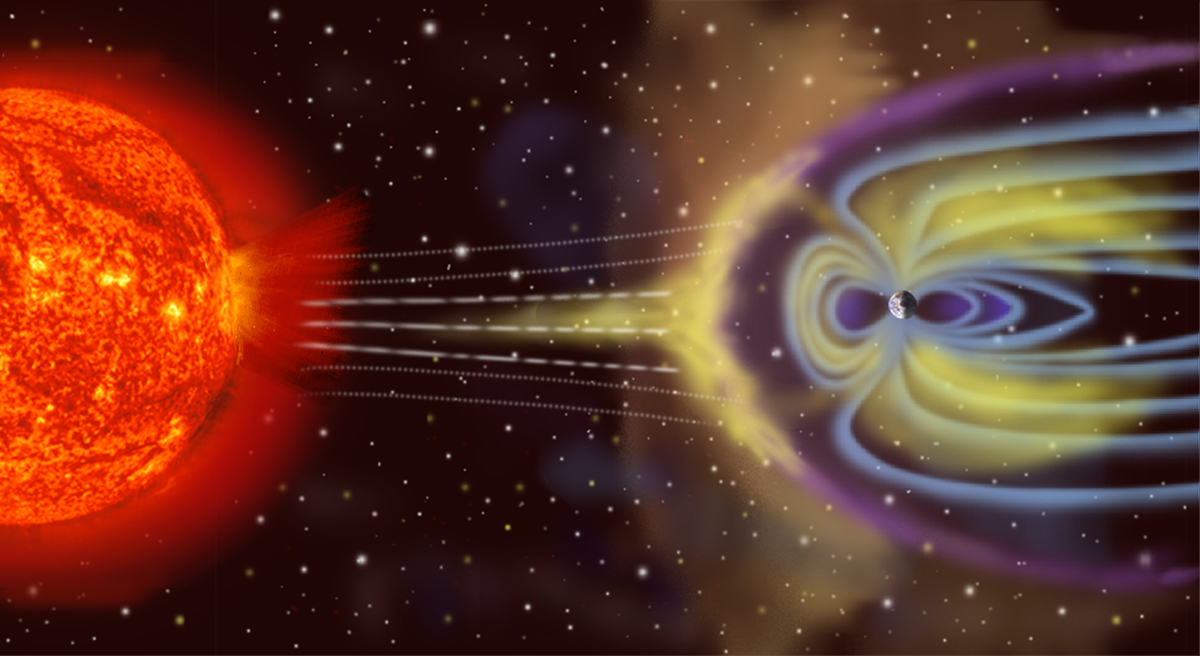

The X1.9 flare released a full-halo coronal mass ejection (CME)—a bubble of plasma and magnetic field ripped from the solar corona and hurled into space.

Type II radio emissions recorded a shock front velocity of approximately 693 kilometers per second, extraordinarily fast for a CME. Typical CMEs travel at 300–500 km/s; this one was in the top 10 percent for speed.

Most critically, the CME’s trajectory pointed directly at Earth. NOAA forecasters immediately issued a G4 (Severe) Geomagnetic Storm Watch based on modeling predictions. The expected arrival window was 24 to 48 hours—enough time for operators to prepare but not enough to implement full defensive measures.

Early Arrival Shock

The CME did not wait 48 hours. At 19:38 UTC on January 19—just 25 hours after the flare—NOAA’s DSCOVR satellite at the L1 point between Earth and the sun detected the shock front arrival.

The CME’s leading edge collided with Earth’s magnetosphere hours ahead of forecast, compressing the protective magnetic envelope and triggering sudden geomagnetic activity spikes.

Operators at utilities, satellite companies, and GPS networks had less-than-expected warning. The early impact surprised forecasters and underscored how unpredictable CME transit times remain, even with modern satellites and modeling. Initial G3 (Strong) conditions escalated rapidly to G4 (Severe)—the second-highest level on the five-point geomagnetic scale.

The S4 Surprise

While attention focused on the geomagnetic storm, a parallel catastrophe unfolded: the January 19 radiation storm reached S4 (Severe) intensity—the strongest solar radiation storm since October 2003, more than 22 years prior. S4 storms create showers of high-energy protons that penetrate satellite shielding and damage semiconductor circuits.

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station were advised to shelter in better-shielded modules. Communications satellites owned by Viasat, Intelsat, and others reported increased bit errors in telemetry, requiring ground operators to reduce data transmission rates.

Polar-orbiting weather satellites experienced sensor anomalies. The radiation event lasted more than 24 hours, making it not just severe but sustained—a one-two punch of geomagnetic and radiative forcing that exposed vulnerabilities in systems designed for “average” space weather, not the extreme.

Infrastructure Under Siege

Power grid operators across North America remained on high alert. While the G4 geomagnetic storm did not trigger widespread blackouts, several utilities reported elevated induced current levels in long transmission lines—the phenomenon that caused the 1989 Quebec blackout during a previous geomagnetic superstorm.

Engineers manually reduced reactive power levels and isolated redundant lines to prevent cascading failures. In the Northeast, New York ISO and PJM Interconnection held emergency conference calls. The threat passed, but the margin of safety was thinner than operators would prefer.

Insurance companies and regulatory bodies began asking uncomfortable questions: How close did the grid come to failure? What investments in magnetic storm hardening are justified?

The 22-State Aurora Forecast

NOAA issued a remarkable prediction: auroras would be visible across 22 to 24 U.S. states as far south as Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia, and even parts of lower-latitude zones under optimal conditions.

The G4 geomagnetic storm was powerful enough to shift the auroral oval—the ring of peak aurora activity—southward to latitudes normally too low to see the lights. Amateur astronomers and northern lights enthusiasts flooded social media with sightings from places that rarely see auroras: the upper Midwest, mid-Atlantic, and even northern Texas skies showed faint green glows.

Professional observatories captured stunning multi-wavelength imagery of the display. For skywatchers, the event was a gift; for infrastructure operators, it was a warning flag.

The Decade’s Trajectory

Space weather forecasters faced uncomfortable reckonings. The current solar cycle was supposed to reach its peak around 2025 and then decline smoothly through the 2030s. Instead, recent months have delivered a cluster of X-class flares, multiple severe radiation storms, and sustained geomagnetic activity.

The sun appears more erratic than models predicted. Some researchers speculate that Solar Cycle 25 may experience multiple peaks—a pattern seen in historical records but poorly understood. If the next decade brings repeated severe storms, power grids, satellites, and communication systems designed with today’s threat assumptions could face inadequate margins.

The January 18–19 events served as a dress rehearsal, exposing gaps in preparedness and forcing global infrastructure operators to reconsider their hardening strategies.

Lessons and Costs

Initial damage assessments suggest the solar flare and radiation storm caused millions of dollars in lost productivity across aviation, maritime, financial services, and agricultural sectors. Satellite operators reported telemetry anomalies and temporary loss of data from earth-observation instruments.

Insurance companies began calculating claims related to GPS failures, communication outages, and operational downtime. The broader message resonated: a single solar flare can touch economies globally within hours. Yet the event also proved that redundancy works—no single point of failure cascaded into systemic collapse. Cell networks operated despite GPS jitter.

Airlines landed safely using backup systems. Power grids held despite magnetic stress. The infrastructure survived, but barely, and observers noted that a slightly stronger storm or faster arrival could have tipped the outcome.

What Comes Next?

The sun remains volatile. Active Region 4341, though the flare decayed, continues rotating across the solar disk and could produce additional eruptions before rotating out of Earth-facing view in early February.

Other active regions are emerging, and solar activity is expected to remain elevated through 2026. The question now is not whether another major flare will occur, but when—and how prepared will we be? Will regulators mandate stronger hardening standards?

Will satellites be redesigned? Will power grids invest in additional magnetic storm shielding? The January 2026 event was a costly but ultimately recoverable warning. As we navigate deeper into Solar Cycle 25’s uncertain trajectory, Earth’s technological civilization faces a humbling truth: the sun’s moods shape our future in ways we are only beginning to fully appreciate and defend against.

Sources:

NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center briefings and alerts, January 18–20, 2026

NOAA SWPC X-class Flare Reports and CME Analysis, January 18, 2026

NOAA SWPC Geomagnetic Storm Updates and Radiation Storm Reports, January 19–20, 2026

NOAA Aurora Forecast and Alerts, January 19–20, 2026

NOAA Solar Cycle Progression Reports

SpaceWeatherLive Solar Activity Database and AR 4341 Archive, January 2026