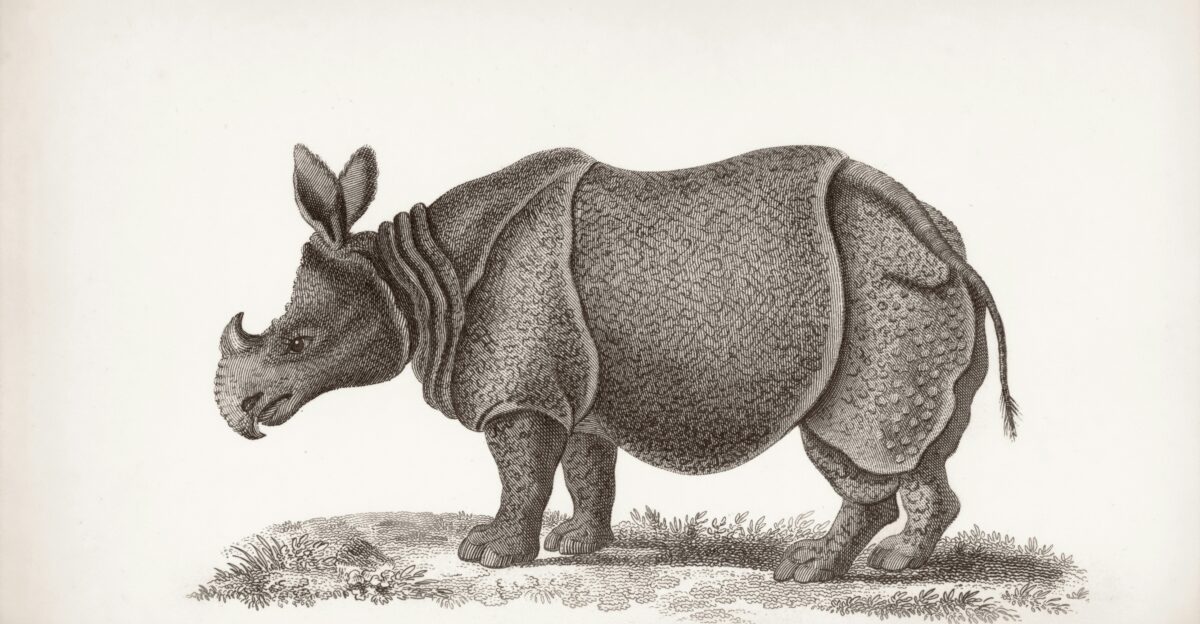

A frozen wolf’s last meal has rewritten the story of one of Earth’s most mysterious extinctions. Paleogeneticists at Stockholm University opened a 14,400-year-old wolf puppy from Siberian permafrost and found intact woolly rhinoceros tissue in its stomach. For the first time, researchers sequenced an entire Ice Age animal genome recovered from another animal’s digestive tract. The results point toward a surprisingly abrupt ending.

A Mammoth Clue Inside A Wolf Pup

Inside a mummified wolf puppy’s stomach, scientists found a 4-by-3 centimeter flesh fragment preserved well enough for DNA work. The tissue dates to about 14,400 years ago, among the youngest woolly rhinoceros specimens known. The wolf was one of 2 “Tumat Puppies” discovered near Tumat, Siberia, between 2011 and 2015, and its meal stayed sealed for millennia. However, stomach preservation creates unusual DNA problems.

Digestive Acids And DNA Contamination Risks

Ancient DNA from permafrost is usually fragmented and scarce, but this sample was tougher. The tissue sat in a wolf’s acidic gut environment for 14,400 years, and predator DNA could mix with prey DNA. Researchers had to separate woolly rhinoceros sequences from wolf sequences without distorting results. With about 2.3% wolf contamination on average, filtering had to be extremely strict. Still, that technical hurdle hid a bigger surprise about extinction timing.

The Student Who Took On The Puzzle

Sólveig Guðjónsdóttir, a Master’s student at Stockholm University’s Centre for Palaeogenetics, led sequencing of the unusual sample. The team made 20 additional DNA extracts from different tissue fragments to improve complexity. Sequencing generated about 88 million reads per extract on average, with depths from 55 to 150 million reads. After quality checks, they identified about 22 million SNPs across 3 woolly rhino genomes. Those numbers set up a revealing comparison across time.

Three Time Capsules Across 35,000 Years

To track genetic change, researchers compared the 14,400-year-old Tumat specimen with 2 older genomes from northeastern Siberia. One dates to about 18,000 years ago, the other to roughly 49,000 years before present. Together, they let scientists estimate population size, inbreeding, diversity, and harmful mutations across tens of millennia. The expected pattern was a decline near extinction, but the data resisted that storyline. The real signal appeared in measures of genetic health.

“Surprisingly Stable” Genetics Before Extinction

“Our analyses showed a surprisingly stable genetic pattern with no change in inbreeding levels through tens of thousands of years prior to the extinction of woolly rhinos,” said Edana Lord, according to January 15, 2026 reporting in Genome Biology and Evolution. All 3 genomes had about 0.4 heterozygous sites per 1,000 base pairs. Long runs of homozygosity stayed rare, arguing against recent inbreeding. So what kills a species that still looks genetically robust?

A Crash Long Before The Final Disappearance

Demographic modeling revealed one major decline between 114,000 and 63,000 years ago, when effective population size dropped from about 15,600 to roughly 1,600. After that, the population stayed remarkably stable until about 14,400 years ago. From 29,700 to 18,530 years ago, breeding woolly rhinos numbered around 10,600. That stability also overlapped with human arrival in northeastern Siberia around 31,600 years ago. Yet the timing of extinction suggests another force took over.

Humans Arrived, Rhinos Still Persisted

“Our results show that the woolly rhinos had a viable population for 15,000 years after the first humans arrived in northeastern Siberia, which suggests that climate warming rather than human hunting caused the extinction,” said Love Dalén, according to January 15, 2026, reporting via Stockholm University. Humans were present about 31,600 years ago, but genomes show no decline during that span. The disappearance came fast, and that speed points toward sudden environmental disruption. A major warming episode fits the calendar.

When The Northern Hemisphere Warmed Fast

The extinction coincides with the Bølling–Allerød interstadial, a rapid warming that began about 14,700 years ago. It lasted roughly 1,900 years, with about 2 degrees Celsius 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of warming overall, much of it concentrated late. In some northern regions, warming may have reached 5 to 10 degrees Celsius. Permafrost thawed, and steppe grasslands shifted toward shrublands and forests, shrinking the woolly rhino’s habitat. The animal’s own adaptations then became part of the problem.

Built For Ice, Not For Sudden Thaw

Genomes show woolly rhinoceros carried adaptations suited for intense cold, including genes linked to cold tolerance and cold perception. Their massive bodies, thick hair, and fat-rich hump worked in the Ice Age steppe but became liabilities in warming landscapes. As open grasslands contracted, shrub tundra and forests spread, limiting the sparse forage these 2-metric-ton herbivores relied on. The population stayed stable for tens of thousands of years, yet the habitat they needed changed quickly. How quickly did extinction strike once conditions shifted?

From Stable To Gone In About 400 Years

Genomic signatures suggest a sudden collapse, not a long demographic fade. The Tumat specimen lived only about 400 years before woolly rhinos vanished around 14,000 years ago, yet its genome shows no gradual decline beforehand. Effective population size appears stable until the extinction boundary, with no measurable reduction as warming began at 14,700 years ago. Researchers noted the event may have been too fast to leave clear genomic warning signals. That leaves room for debate, because extinction arguments rarely end cleanly.

Climate Versus Hunting Still Sparks Disputes

Megafaunal extinctions often trigger one question: did humans or climate do it? Some research, including work linked to Denmark’s ECONOVO center, argues human hunting drove major losses over the past 50,000 years, from 57 megaherbivore species then to 11 today. But woolly rhino genomes tell a different story, showing stability despite 15,000 years of human presence. The timing also matches Bølling–Allerød warming closely. That contrast hints extinction causes may differ sharply by species, even in the same era.

The Strange Backstory Of The Tumat Puppies

The wolf puppy preserving rhino tissue came from a pair of permafrost finds called the “Tumat Puppies,” discovered between 2011 and 2015. They were found near mammoth bones that showed signs of human butchering, fueling theories about early dogs. A June 2025 study instead identified them as wolf cubs using chemical fingerprints in bones, teeth, and tissue. The undigested rhino flesh suggests the cub died soon after eating, possibly fed scraps by its pack. That accident created the perfect genetic time capsule for scientists.

“Really Exciting,” And Technically Brutal

“It was really exciting, but also very challenging, to extract a complete genome from such an unusual sample,” said Sólveig Guðjónsdóttir, according to January 2026 reporting from multiple sources. The team produced 22 DNA extracts, excluding 1 due to heavy wolf contamination. Across remaining samples, average wolf mitogenome contamination stayed at 2.3%. Strict filtering during variant calling removed predator DNA signals in nuclear analysis. The payoff was a high-coverage woolly rhino genome at about 10 times depth. That success changed what counts as usable ancient DNA material.

A Thesis Project That Turned Global

Guðjónsdóttir, from Iceland, joined the Nordic Master’s Programme in Biodiversity and Systematics and contacted Love Dalén at Stockholm University’s Centre for Palaeogenetics. There, she learned about the project involving tissue from one of the last woolly rhinos. She spent about 6 months in the lab, then moved into analysis and thesis writing. The work became the core of a peer-reviewed paper in Genome Biology and Evolution in January 2026 and drew major media attention. Her path shows how early-career researchers can reshape big scientific debates.

A Climate Message Hidden In Ancient Genes

“Rapid global warming was the predominant factor driving the total extinction of mammoths and rhinos in frigid zones from the Late Pleistocene,” according to Royal Society of London research cited across peer-reviewed sources from January 2026. In the woolly rhino case, the genetic story supports climate pressure over hunting. Ecosystems shifted as warming replaced open grasslands with shrubs and forest, and cold-adapted megaherbivores could not adjust fast enough. The genomes show no inbreeding stress or slow decline before the end, only a habitat shock. Still, real-world extinctions often vary by region, complicating any single explanation.

Lessons For Today’s Conservation Choices

“Recovering genomes from individuals that lived right before extinction is challenging, but it can provide important clues on what caused the species to disappear, which may also be relevant for the conservation of endangered species today,” said Camilo Chacón-Duque, according to January 2026 reporting. Woolly rhinos appear genetically healthy, showing that diversity alone cannot prevent extinction if habitat collapses quickly. Conservation planning has to weigh genetics alongside fast environmental shifts, especially climate-driven ones. The case warns that ecological vulnerability can arrive suddenly, even in a stable population. That warning resonates beyond Siberia, reaching global extinction patterns.

Megafaunal Losses Were Uneven Worldwide

Late Pleistocene extinction was not uniform across continents. About 65% of megafaunal species worldwide disappeared, including 72% in North America, 83% in South America, and 88% in Australia. Africa lost about 21%, possibly because hominins coevolved longer with African mammals. These differences suggest multiple drivers, including human pressure, climate shifts, and combined effects. Woolly rhinoceros extinction appears heavily climate-linked, contrasting with regions where hunting may dominate. Those contrasts raise a broader question: how many extinct species might look “healthy” genetically right before vanishing?

Ancient DNA Tools Are Expanding Fast

Sequencing a genome from wolf stomach contents highlights how rapidly paleogenomics is advancing. Researchers once depended mostly on bones, teeth, or exposed preserved tissue, but this work shows unexpected reservoirs can hold high-quality DNA. High-throughput methods can process 96 extracts in about 4 hours, cutting costs by about 39% while preserving quality. Combined with contamination filtering and demographic reconstruction, these approaches allow more complete histories from smaller samples. As methods improve, scientists can test extinction hypotheses with tighter timelines. That growing power is already feeding another controversial frontier.

The Bigger Ice Age Puzzle Still Isn’t Settled

Woolly rhino extinction is one thread in a 50,000-year tapestry of losses. Some species, such as woolly mammoths, may have persisted into the early Holocene, while others vanished earlier. In North America, the Younger Dryas period from 12,900 to 11,700 years ago coincided with peak extinctions, but it occurred after woolly rhinos were gone. The drivers likely differed by place and species, mixing climate swings, habitat shifts, hunting pressure, and ecosystem cascades. The wolf pup genome adds clarity, yet it also shows how sudden endings can be. What other answers might be sitting inside overlooked remains?

A Sobering Takeaway From The Permafrost

The genome recovered from the wolf puppy delivers a stark lesson: genetic health cannot guarantee survival when the environment changes too fast. Woolly rhinos appear to have stayed stable for about 50,000 years, then disappeared in roughly 400 as warming reshaped habitat. For modern conservation, that means protecting diversity is necessary but not sufficient without safeguarding ecosystems and climate resilience. The finding also reframes extinction as something that can look sudden even when populations seem fine on paper. In that sense, an Ice Age wolf’s last meal became a warning timed for today.

Sources

Genome Shows no Recent Inbreeding in Near-Extinction Woolly Rhinoceros Sample Found in Ancient Wolf’s Stomach. Genome Biology and Evolution, January 2026

Woolly rhino genome recovered from Ice Age wolf stomach. Stockholm University Communications Office, January 15, 2026

Masters student in the forefront of research. Stockholm University News, January 16, 2026