On the harsh surface of Mars, where every resource counts, scientists are turning human sweat and urine into a vital building material, binding the planet’s loose regolith into sturdy, concrete-like blocks for future habitats.

This innovation, known as AstroCrete, mixes Martian soil simulants with urea and proteins like human serum albumin (HSA) to create low-energy composites. Laboratory tests reveal strengths matching Earth sidewalks, ideal for Mars’ low gravity, which is just 38 percent of Earth’s. By using human byproducts, the method cuts dependence on costly Earth shipments and conserves scarce water.

Historical Foundations

NASA’s pursuit of regolith-based building traces to 1970s lunar experiments with sintering and sulfur concretes.

Those approaches demanded high energy, impractical for Mars outposts. Research evolved in the 2010s toward bio-inspired binders, blending soil simulants with organic compounds for viable alternatives.

The AstroCrete Breakthrough

Developed in labs, AstroCrete relies on HSA as a protein binder that solidifies regolith. Adding urea boosts plasticity, cuts brittleness, and enhances toughness by reshaping protein chains under stress.

Compression tests confirm performance akin to non-load-bearing terrestrial concrete, marking a pioneering low-energy, biology-aided technique.

Why Urea and Proteins Excel

Urea, abundant in sweat and urine, acts as a plasticizer without extra water needs—a critical edge on water-poor Mars.

Regolith, rich in silicates, iron oxides, and fine dust, packs well but stays inert sans binders. However, toxic perchlorates demand removal for safe handling.

Processing and Biological Pathways

Mars’ cold, low-pressure environment and dust storms challenge mixing, requiring sealed systems and low-power methods. AstroCrete uses minimal water via protein denaturation, unlike water-heavy traditional concrete.

Complementary techniques like microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) employ bacteria to turn urea into cementing carbonates, offering self-replicating options despite lower initial strengths.

Strengths and Applications

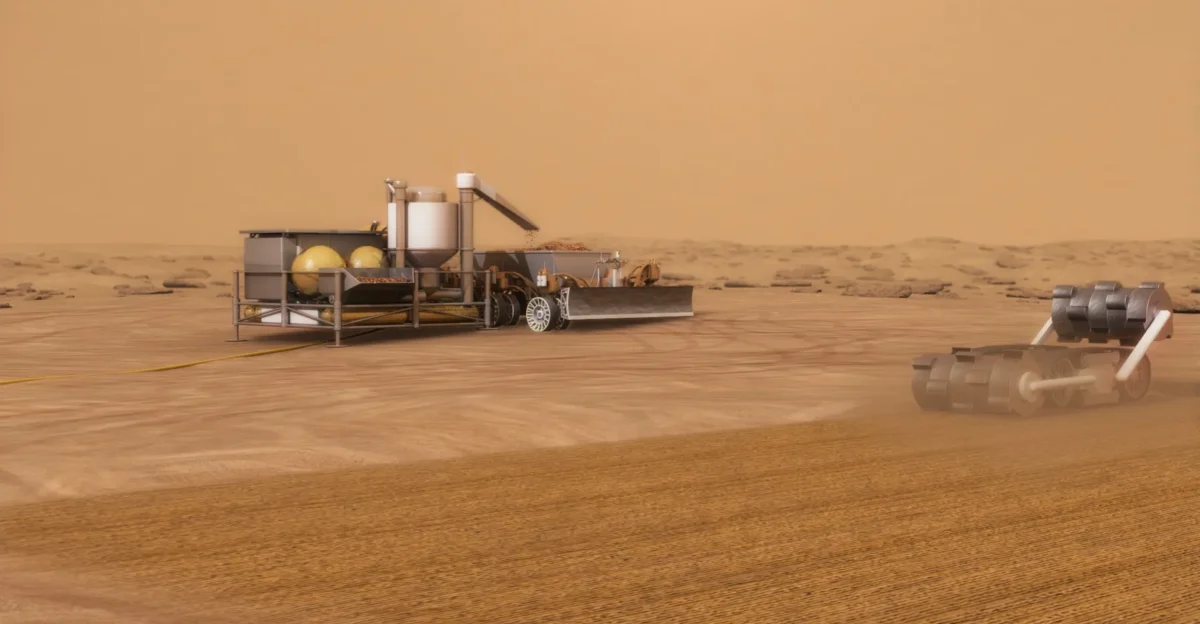

These materials suit pressurized habitats, 3D-printed walls, and radiation shields. Regolith’s density blocks cosmic rays and solar particles effectively in thick layers. On Mars’ weaker gravity, moderate strengths suffice for enclosures.

Compatibility with extrusion printing allows robotic on-site fabrication, recycling excavation waste into structures.

Challenges and Safeguards

Perchlorates, dust abrasion, thermal swings, UV exposure, and storms test durability. Early simulations show protein composites holding up, with coatings eyed for longevity.

Binders stay non-pathogenic, using Earth-proven strains; containment prevents contamination. Production scales via automation, supplementing oxygen extraction and metal refining in closed loops.

Economic and Strategic Edges

Launching a kilogram from Earth costs millions; human-derived binders recycle byproducts into infrastructure, slashing expenses.

Versus energy-intensive sintering or sulfur concrete, bio-composites demand less power and gear, fitting habitats over heavy machinery.

Current Status and Next Steps

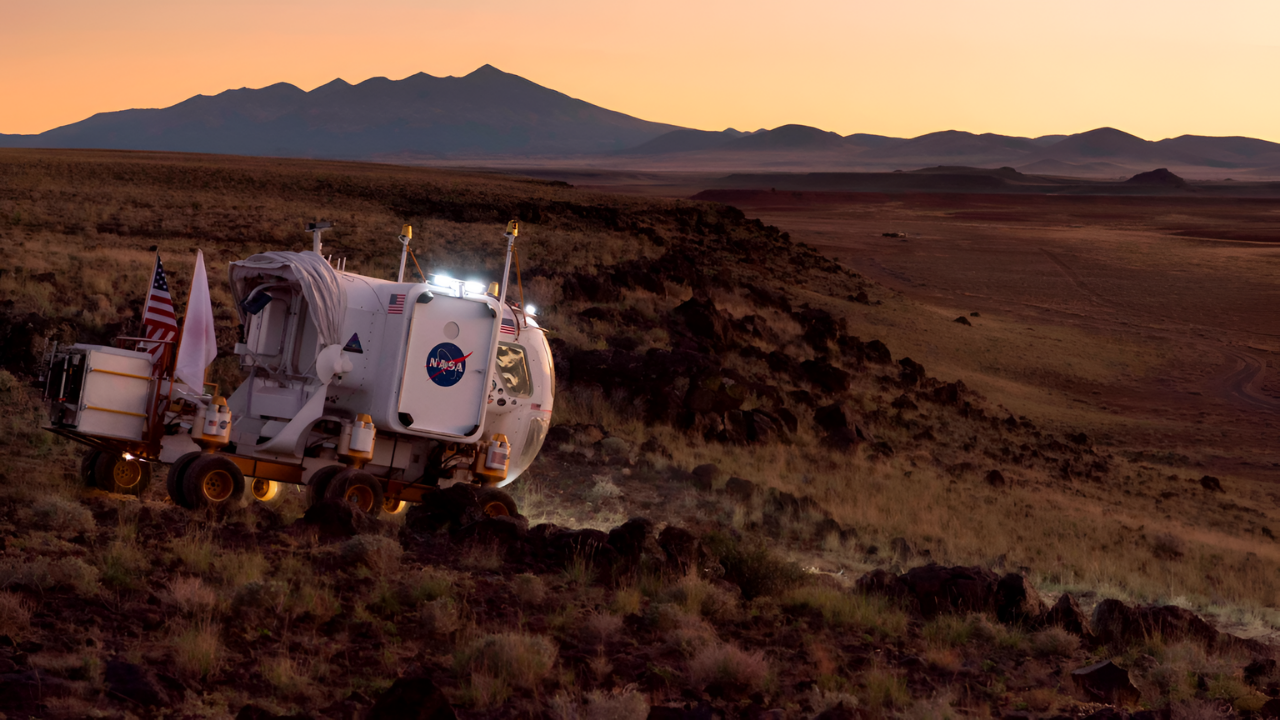

Still lab-bound, AstroCrete awaits space demos for protein extraction, storage, and scaling. Tests on the International Space Station and lunar sites will probe microgravity and automation. As ISRU matures, it promises integration with broader systems.

This shift toward biological-mechanical synergy could enable self-reliant Mars bases, turning explorers’ waste into shelters and advancing sustainable off-world living.[1][2]

Sources:

- Title: Blood, sweat, and tears: extraterrestrial regolith biocomposites with in vivo binders, Publication: Materials Today Bio (2021), PMC.

- Title: Microbial induced calcite precipitation can consolidate martian and lunar regolith simulants, Publication: PLOS ONE (2022).