Somewhere on Earth, a species is dying. Last October, scientists released the 2025 IUCN Red List. The number inside stopped experts cold: nearly 49,000 species now teeter on the brink of extinction. But the real shock wasn’t the total.

It was the six animal species that had already crossed the point of no return—officially, irreversibly gone. These weren’t predictions. These were confirmations of species that vanished while we were looking the other way.

The Data That Changed Everything

The IUCN Red List, established in 1964, serves as humanity’s most rigorous accounting of life on the edge. On October 10, 2025, scientists announced what the data revealed: six animal species and two plant species were officially declared extinct. But here’s what makes this moment different: these weren’t guesses. These were confirmations.

Species didn’t vanish yesterday. They vanished while we were looking away, and only now are we accepting the evidence that they’re truly gone forever.

How Extinction Declarations Work

Before the IUCN can declare a species extinct, researchers must exhaust every avenue of hope. They conduct surveys, search habitats, rule out hidden populations, and verify museum records. This scientific caution is appropriate and necessary.

It creates a cruel reality: by the time extinction is officially confirmed, the species has usually been gone for decades.

Understanding the Scope of Loss

Each of the six species declared extinct represents millions of years of evolution permanently erased. Some vanished from continent-spanning territories. Others disappeared from tiny islands. Some scientists watched them slip away.

Others discovered they were gone only through archival research. Together, they confirm what conservationists already knew: extinction is accelerating, and official declarations always arrive too late.

Extinction 1—A Bird That Crossed Three Continents

“The extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew is a tragic and sobering moment for migratory bird conservation,” said Amy Fraenkel, executive secretary of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals.

The word “tragic” carries weight. It’s not scientific. It’s a confession. Somewhere across Europe, North Africa, and Asia, protection measures that should have been implemented weren’t.

A Century Of Decline, A Moment Of Finality

The first-ever recorded global bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa, and West Asia represents more than just the loss of a species. It represents a century of failed protection. Researchers documented the decline as early as 1912.

As the bird’s population crashed across three continents, migration routes altered, wetlands drained, and hunting continued. By the mid-1990s, the last threshold was crossed.

Extinction #2—An Island’s Only Mammal Dies Silent

On Christmas Island, a remote speck in the Indian Ocean, something unseen happened for forty years. The island’s only native shrew—a tiny creature with no name recognition, no conservation campaign—simply vanished from human sight.

Scientists last captured a living specimen in 1985. For four decades, researchers searched. They set traps. They surveyed. They hoped. Nothing.

A Shipment Of Hay Destroyed Everything

Here’s the story that haunts extinction researchers: a visiting ship in the early 1900s accidentally delivered black rats hidden inside bales of hay to Christmas Island. Those rats carried a blood-borne parasite that devastated endemic species.

Two native rat species vanished. The shrew population crashed. Then feral cats arrived. Then yellow crazy ants. Then wolf snakes. Each invader was an accident. None were malicious. All were catastrophic.

Extinction #3—The Cone Snail: Nearly 40 Years Lost To Silence

A small cone snail species, Conus lugubris, joined the extinction list after vanishing from scientific observation for nearly four decades. The last specimens were collected in 1987 from coastal waters near Cape Verde. Scientists searched. They dredged. They hoped to find populations in reef refuges. Nothing.

The cone snail represents thousands of marine species similarly vanishing without fanfare, their existence confirmed only by museum specimens.

An Ocean’s Loss, A Warning Unheeded

Marine extinctions receive less attention than terrestrial ones, yet they may be more common. The cone snail’s loss represents an entire lineage of venomous mollusks that evolved specialized predation tactics over millions of years.

When that lineage vanishes, the ocean loses not just a species but an evolutionary strategy, a set of biochemical innovations.

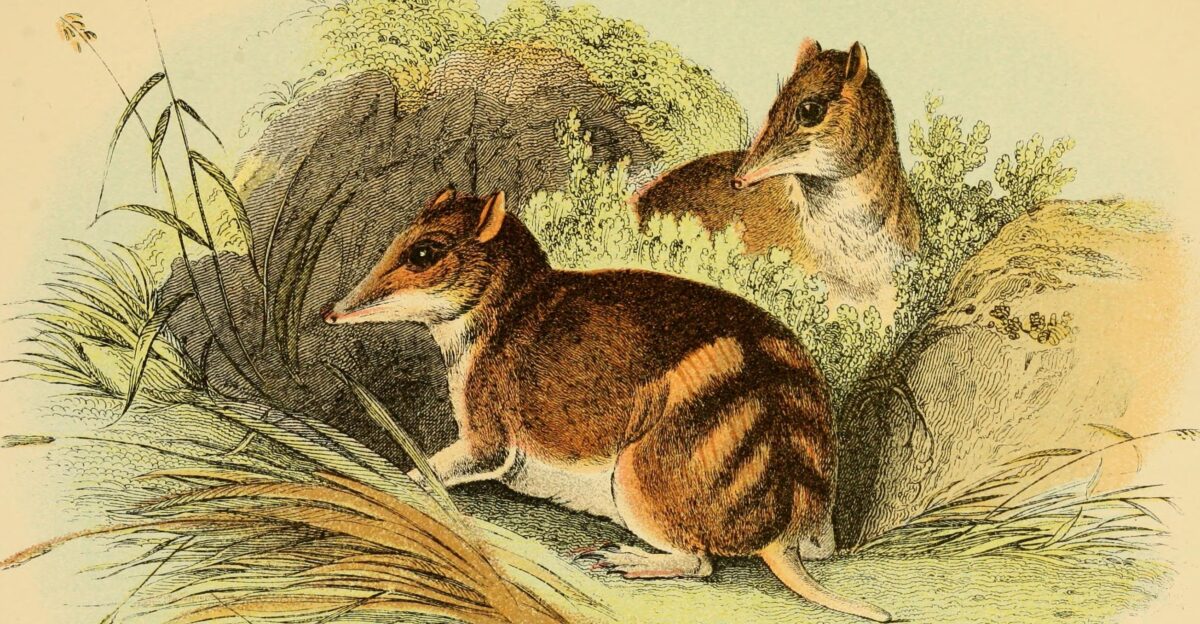

Extinction #4—An Australian Mammal Lost To Time

The marl, also known as the south-western barred bandicoot (Perameles myosuros), represents one of Australia’s earliest recorded extinctions. The last confirmed specimen was collected in 1907 in southwestern Australia.

Scientists of that era documented the species briefly, captured individuals, and then watched as it disappeared entirely from the landscape.

What Early Extinction Teaches Us

The marl’s loss occurred during Australia’s period of rapid European settlement, when continent-scale habitat transformation was proceeding without restraint or understanding of consequences. The species couldn’t adapt to the new world being built around it.

Its extinction happened quietly, recorded in museum catalogs and field journals, but never sparking the kind of international alarm that might have triggered protection elsewhere.

Extinction #5—Lost In The Late 1800s

The south-eastern striped bandicoot (Perameles notina) vanished into extinction in the late 1800s as Australia transformed from wilderness to colony. The species inhabited southeastern Australia, where it faced the combined pressures of habitat conversion, introduced predators, and hunting.

The last known specimen was collected in 1857. It exists now only in museum collections and historical records.

Australia’s Pattern Emerges

The south-eastern striped bandicoot’s extinction is not unique in Australia. It’s part of a pattern that makes Australia the global capital of mammal extinctions. Between 1788 and now, between 34 and 40 terrestrial mammals have vanished from Australia—more than ten percent of all species that existed before European settlement.

Each extinction followed similar patterns: habitat loss, invasive predators, and rapid environmental change.

Extinction #6—The Last Sighting Nearly 100 Years Ago

The Nullarbor barred bandicoot (Perameles papillon) was last confirmed alive in 1928 on the Nullarbor Plain, a vast, remote limestone plateau spanning the border between South Australia and Western Australia.

That sighting, documented nearly a century ago, remains the most recent evidence of the species’ existence. Since then: nothing.

How Remoteness Offers No Protection

The extinction of the Nullarbor barred bandicoot is perhaps the most puzzling of Australia’s mammal losses. The species lived on one of Earth’s most isolated plateaus, seemingly protected by vast distances and harsh terrain. Yet isolation couldn’t save it.

Introduction of feral cats and foxes in the early 1900s, even to remote regions, proved catastrophic. The bandicoot had no evolutionary history with such predators. Its survival mechanisms—small size, nocturnal behavior, burrowing—offered no defense against animals that hunted by different rules.

The Cruel Delay

Here’s the cruel reality complicating extinction prevention: formal extinction declarations lag decades behind actual loss. The Christmas Island shrew’s last confirmed sighting was in 1985. Its official extinction declaration came in 2025. Forty years of silence.

Before the IUCN can declare a species extinct, researchers must exhaust every avenue. Surveys must be conducted. Habitat must be searched. Hidden populations must be ruled out.

Hidden Extinctions In Plain Sight

The 2025 IUCN declaration confirmed the official extinction of six animal species and two plant species, totaling eight. Yet this formal list represents only a fraction of what’s actually vanishing. An Australian study estimated roughly 9,000 to 10,000 invertebrate species have disappeared since 1788.

Nine thousand species dwarfs the 100 formally listed Australian extinctions by a factor of 100. Most vanished before science knew they existed. How many species have we lost without ever knowing they lived?

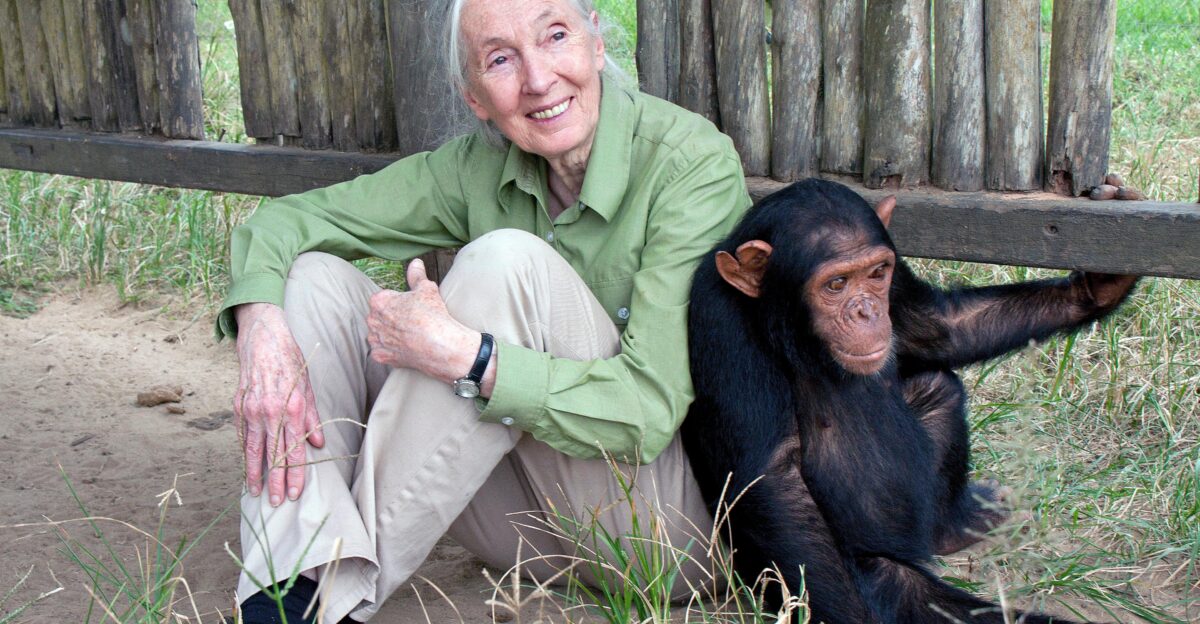

A Recovery That Gives One Reason For Hope

Not all extinction stories end in failure. The green sea turtle, once hunted to near extinction in the twentieth century, has made a remarkable recovery in many ocean regions. Through international protection agreements, nesting site safeguards, and sustained commitment, turtle populations rebounded dramatically—increasing 28% since the 1970s.

Sea turtles prove extinction isn’t inevitable. That coordinated action works. That even after decades of decline, species can recover—if action comes before the point of no return.

The Choice Belongs To Us

“We’ve failed the shrew, and we’ve failed many other species, and we continue to fail,” John Woinarski told The Conversation. His words aren’t despair—they’re clarity. With 49,000 species now threatened, the window for preventing further losses narrows with every year we postpone habitat protection, invasive species management, and climate action.

The slender-billed curlew’s final sighting was in 1995. Its extinction declaration came in 2025. Will we spend the next thirty years watching the Eurasian curlew follow the same path? The choice isn’t nature’s. It’s ours. And the clock is running out.

Sources:

IUCN Red List October 2025 Update

Mongabay: “The slender-billed curlew, a migratory waterbird, is officially extinct”

ABC News: “Christmas Island shrew declared extinct after decades”

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) Statement

The Conversation: “Around 9,000 species have already gone extinct in Australia”

Great News Global: “Green sea turtles rebound worldwide, marking a 28% rise since the 1970s”