The National Weather Service issued urgent flood warnings across three states on January 11, 2026, as rivers swelled to dangerous levels following heavy precipitation. Washington, Mississippi, and Louisiana braced for imminent inundation of roads, homes, and farmland.

Officials issued a stark warning to the public: “Turn around, don’t drown when encountering flooded roads.” The warnings came as atmospheric conditions pushed water levels 2 to 4 feet above historical flood stages, creating conditions NWS described as “minor to moderate flooding” through mid-January.

Cascade Effect

Seven distinct rivers surged simultaneously across the Pacific Northwest and Deep South, an unusual geographic span suggesting a coordinated weather system driving precipitation across thousands of miles. The Skokomish River in Washington peaked at 17.6 feet, one foot above flood stage, while the Chickasawhay River in Mississippi reached 23.5 feet, exceeding its flood threshold by 3.5 feet.

In Louisiana, multiple rivers crested within hours of each other, compounding rescue and response challenges. The geographic dispersion underscored the scale of the atmospheric anomaly fueling the floods.

Historical Context

River flooding remains one of the costliest natural hazards in the United States, accounting for an estimated 200–500 deaths annually and billions in property damage. The “Turn Around, Don’t Drown” (TADD) campaign, launched by NWS in 1999, emerged after data showed more than 50% of flood fatalities occurred when drivers attempted to cross inundated roadways.

January flooding is less common than spring or fall floods, making simultaneous warnings in three states in mid-January rare and alarming. NWS flood research indicates that drivers cannot accurately judge water depth or current speed at night.

Infrastructure Vulnerability

Roads spanning rural and suburban areas in all three states lacked sufficient elevation or drainage infrastructure to handle water levels 2–4 feet above historical norms. Highway 106 in Washington, Highway 22 in Louisiana, and county routes in Mississippi serve as critical evacuation and commercial corridors, making their closure economically disruptive.

Local governments reported that some barricades had to be deployed overnight, trapping late-returning residents who discovered roads underwater. The compressed timeline of many rivers cresting within 24–48 hours left a minimal preparation window for affected counties and parishes.

Roads Cut Off, Homes Threatened

At least six major roads across the three states became impassable as floodwaters rose: Skokomish Valley Road and Highway 106 in Mason County, Washington; Highway 22 south of Robert in Louisiana; Louisiana Highways 10 and 21 near Franklinton; and multiple county routes in Mississippi’s George, Greene, and Perry Counties.

NWS warnings explicitly named residential neighborhoods facing imminent danger, including Bogue Chitto Heights Subdivision in Louisiana, where officials warned “some homes will be damaged.” Hundreds of residential structures were located in low-lying zones, with families ordered to evacuate or prepare for potential water intrusion. The convergence of multiple overflowing rivers created cascading impact zones where water backed up through tributaries.

Washington’s Pacific Deluge

The Skokomish River at Potlatch, Washington, peaked at 17.6 feet, surpassing its 16.5-foot flood stage, submerging Skokomish Valley Road, Bourgault Road West, and Purdy Cutoff Road. Mason County officials reported “deep and quick flood waters inundating some residential areas,” with families evacuating north of the river valley.

The Skokomish drains the Olympic Mountain foothills into Hood Canal, a low-lying region vulnerable to rapid runoff. Highway 106, a principal north–south route, remained closed through January 13, disrupting commuter and commercial traffic. NWS forecasted continued elevation through midweek, meaning road closures would extend 5–7 days.

Mississippi’s Double Crisis

Mississippi faced a dual flood threat as the Chickasawhay River at Leakesville and the Leaf River near McLain both exceeded flood stage within hours. The Chickasawhay crested at 23.5 feet, 3.5 feet above the 20-foot threshold, while the Leaf climbed to 21.3 feet and was forecast to peak at 22 feet by Wednesday.

NWS stated: “At 22.0 feet, flooding of lowlands continues and some roads in low-lying areas become cut off by high water.” George, Greene, and Perry Counties coordinated emergency response across two river basins simultaneously. Farmers were urged to relocate livestock and equipment to higher ground, with warnings that pastures and barns would be inundated.

Louisiana’s Triple Threat

Louisiana confronted flooding on three major river systems: the Tangipahoa River near Robert, the Tickfaw River near Holden, and the Bogue Chitto River at Franklinton and near Bush. The Bogue Chitto at Franklinton was forecast to reach 16 feet above its 12-foot flood stage, prompting NWS to warn: “Homes on the west bank north of Louisiana Highway 10 will flood.” The Tickfaw was expected to crest at 18.5 feet, 3.5 feet above flood stage, affecting Livingston Parish.

The Tangipahoa’s rise threatened Highway 22 south of Robert, a major regional artery. All three rivers peak within overlapping 36–48 hour windows, stretching parish emergency services to the limit.

Ecosystem & Agricultural Impact

Beyond residential and traffic disruptions, flooding threatened vast agricultural zones and wildlife habitats across all three states. Farmers in Mississippi and Louisiana reported that crop fields, hay pastures, and livestock facilities were located in flood zones, with evacuation timelines measured in hours.

The Bogue Chitto Wildlife Management Area, a central recreational fishing area, faced inundation, cutting off access roads and temporarily halting hunting and fishing activities. Environmental agencies warned that floodwaters would carry agricultural chemicals, sewage overflow, and debris into downstream ecosystems, including sensitive estuaries in Louisiana. Recovery of contaminated land and water systems could extend months beyond the time it takes for the water to recede.

Night Flooding: Hidden Peril

The NWS emphasized a critical secondary danger: floodwaters occurring at night obscure road conditions, making it nearly impossible for drivers to identify submerged roads. The agency stated: “Most flood deaths occur in vehicles. Turn around, don’t drown when encountering flooded roads.” Several affected highways, particularly rural stretches of Highway 22 in Louisiana and county routes in Mississippi, lack robust street lighting, amplifying the risk.

Residents returning late from work or relatives attempting emergency travel faced heightened collision and drowning hazards. Emergency dispatchers reported calls from drivers stranded in vehicles after encountering unexpected water, a scenario NWS has documented as the leading cause of flood-related mortality in rural regions.

Emergency Response Coordination

County and parish emergency management offices activated disaster response protocols, coordinating with state and federal agencies to establish shelters and distribute resources. Mason County, Washington; George, Greene, and Perry Counties in Mississippi; and St. Tammany, Livingston, and St. Helena Parishes in Louisiana all declared local states of emergency.

The NWS provided hourly updates to emergency managers, enabling real-time adjustments to evacuation zones and shelter placement. However, officials acknowledged that the simultaneous activation across three states strained mutual aid agreements, as neighboring jurisdictions also faced flooding or near-flood conditions. Red Cross chapters mobilized volunteers and opened shelters for up to 500 displaced residents.

Forecast Uncertainty & Extended Warnings

A complicating factor for emergency managers was the open-ended nature of some NWS warnings, issued “until further notice” rather than with fixed expiration times. This reflected continued uncertainty about whether additional precipitation would occur or whether already-saturated soils would sustain flooding longer than typical for the season.

Some warnings extended through January 17 or beyond, meaning road closures, evacuations, and shelter operations could persist for a week or more. Governors’ offices in Washington and Louisiana issued cautionary statements urging residents and businesses to prepare for potential prolonged disruptions. Insurance companies braced for a surge in claims, dispatching adjusters to affected areas.

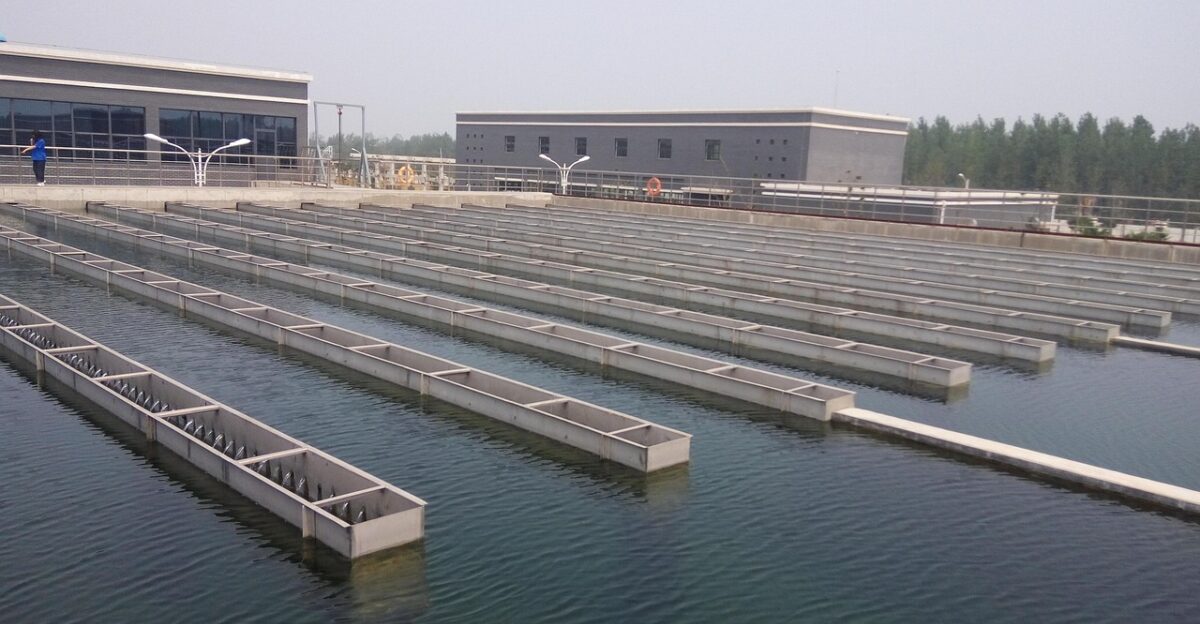

Water Supply & Sanitation Concerns

Beyond roads and homes, flooding posed secondary public health threats. Water treatment plants in flood-prone areas risked contamination or operational disruption if intake structures or backup power systems were submerged. Local public health departments issued advisories advising residents to boil water if the supply was compromised.

Septic systems and municipal sewage treatment facilities in low-lying zones faced backflow risks, creating hazards of sewage contamination. Concerns about water-borne pathogens prompted public health officials to monitor for illnesses in affected populations after the flood. These secondary impacts can persist for weeks after the water recedes, necessitating environmental testing and remediation.

Livestock & Property Loss Assessment

Farmers across Mississippi and Louisiana reported significant losses of cattle, poultry, and equipment that were unable to be evacuated promptly. Extension Services estimated that hundreds of head of livestock and millions of dollars in farm equipment faced inundation. Barns, feed storage, and irrigation infrastructure in flood zones would require inspection and potential replacement.

Insurance claims for livestock and property damage began accumulating within hours of water entering farmsteads. Rural communities, where agriculture remains economically critical, faced compounded economic hardship beyond the immediate flood event. Recovery funding from state and federal disaster programs typically takes months to disburse.

Climate & Weather Pattern Questions

The simultaneous flooding of rivers across three geographically distant states, from the Pacific Northwest to the Deep South, raised questions among meteorologists about the underlying atmospheric driver. A persistent high-pressure system or tropical moisture intrusion could explain the phenomenon, though forecasters were cautious about making definitive attributions.

Climate scientists noted that warming temperatures can increase atmospheric moisture capacity, potentially intensifying precipitation events. However, attributing this specific event to climate change requires longer-term pattern analysis rather than single-event assessment. Forward-looking questions persisted: Would winter 2026–27 see similar events, and are flood infrastructure investments keeping pace with intensifying precipitation?

Federal Disaster Declarations & Funding

As water levels crested, state governors moved to request federal disaster declarations, a formal process enabling FEMA funding for response and recovery. Federal funding covers emergency protective measures, debris removal, and uninsured property losses above state recovery capacity. The process typically takes weeks for full activation, creating a funding gap for immediate needs.

Previous major flooding events (2005 Hurricane Katrina, 2017 Hurricane Harvey) demonstrated that federal recovery funds often expire before full reconstruction, leaving communities to close remaining gaps through local bonds and private fundraising. The 2026 flooding, while regional rather than national, would still strain federal disaster relief budgets if declarations were granted to all three states.

Interstate & Cross-Boundary Challenges

Flooding on rivers spanning state lines, particularly the Pearl River between Louisiana and Mississippi, required coordination between state environmental and water management agencies. Downstream states rely on the dam operations and flood mitigation decisions of upstream states, which can create potential friction over water release timing and elevation targets.

Interstate water compacts and memoranda of understanding guide such decisions, but real-time pressures can create conflicts. Louisiana’s concerns about rapid water level rises conflicted with Mississippi’s need to lower reservoirs, illustrating the governance complexity in multi-state river basins. Federal mediation, facilitated through the Army Corps of Engineers, helped manage these tensions during the flooding event.

Insurance & Economic Ripple Effects

Property insurers in flood-prone areas reported a surge in claim volume as homeowners and businesses documented their losses. Uninsured and underinsured residents faced devastating financial consequences, with repair costs ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Local tax bases in affected counties would suffer a short-term revenue loss if damaged properties qualified for tax reductions or exemptions during the recovery period.

Businesses unable to operate during road closures experienced revenue loss, with some facing permanent closure if recovery took months to achieve. Regional economic data for Q1 2026 would likely reflect the disaster’s impact on employment, income, and retail activity in affected zones.

Infrastructure Resilience & Future Planning

The 2026 flooding intensified an ongoing policy debate about whether road, bridge, and drainage infrastructure in flood-prone regions adequately accounts for historical and projected flood frequencies. Some infrastructure, built to 50-year or 100-year flood standards, may require elevation, replacement, or bypassing to withstand intensifying precipitation events.

State and local governments face budget constraints when retrofitting aging infrastructure, forcing difficult prioritization decisions. Public works departments began post-flood inspections to assess structural damage and design needs for future resilience. Long-term planning documents would incorporate lessons from this event, although implementation would take years and billions of dollars in capital investment.

Lessons in Preparedness & Adaptation

The January 2026 flooding underscored the importance of preemptive NWS warnings, accessible emergency information, and public awareness campaigns like “Turn Around, Don’t Drown.” Communities that had invested in siren systems, social media alert networks, and shelter pre-positioning experienced faster and more organized evacuations, resulting in fewer casualties.

Conversely, isolated rural areas with limited connectivity and aging warning systems faced delayed notifications and chaotic responses. Moving forward, emergency management experts emphasized the need for redundant warning systems, regular disaster drills, and community education about flood risks. The broader lesson is that climate variability and intensifying precipitation events require constant vigilance and adaptive infrastructure planning, not complacency.

Sources:

National Weather Service Flood Warnings (Washington, Mississippi, Louisiana) – January 11–14, 2026

NOAA Water Gauges Real-Time River Level Data – Skokomish, Chickasawhay, Leaf, Tangipahoa, Tickfaw, Bogue Chitto, and Pearl Rivers

National Weather Service Turn Around Don’t Drown Campaign & Safety History

FEMA Disaster Declaration Process & Federal Recovery Funding Guidelines

U.S. Agricultural Extension Services Livestock & Farm Equipment Loss Assessments – January 2026

Army Corps of Engineers Interstate Water Management & Coordination Records – January 2026