Over the open south-central Indian Ocean, Dudzai began as a relatively modest storm, then suddenly found near-perfect fuel beneath it. Sea temperatures hovered above 26.5°C, the rough threshold scientists say cyclones need to thrive, and in places were even warmer, giving the storm a deep reserve of heat and moisture.

Over just a few hours, winds jumped from about 70 mph to well over 130 mph, pushing the system into the ranks of the season’s most dangerous storms. Remote islands and shipping crews watched nervously as waves built to heights of 8 meters and more, knowing that even a distant cyclone can send damaging swells across the ocean.

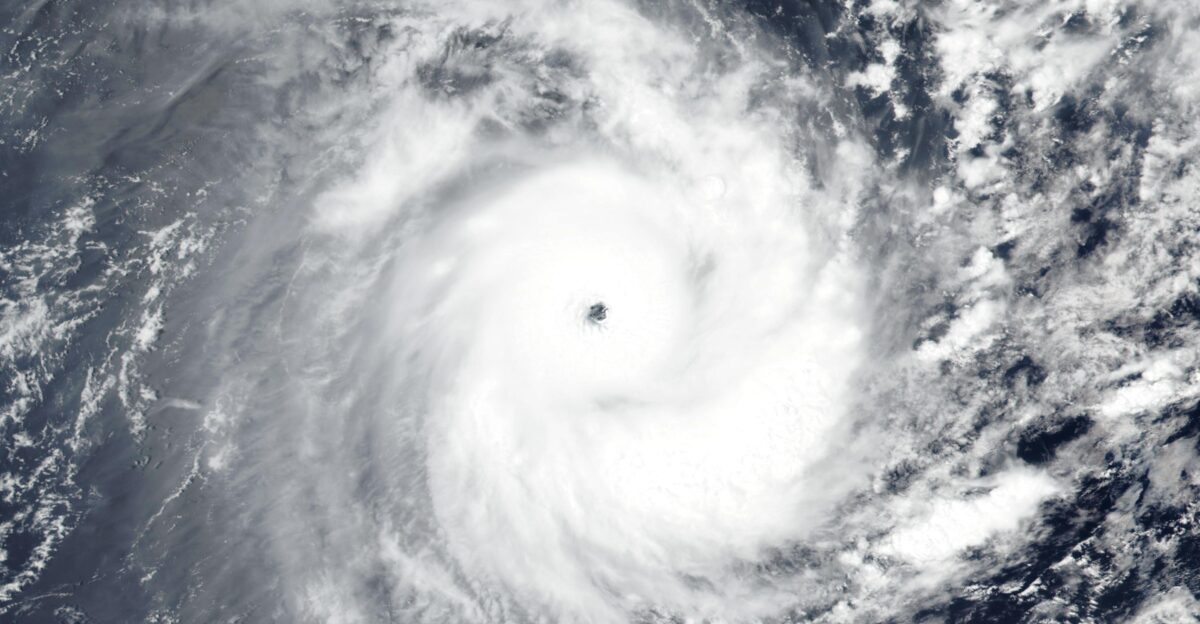

Rapid Surge

As Dudzai strengthened, its transformation became textbook rapid intensification: sustained winds nearly doubled in just 24 hours and central pressure crashed below 950 hPa, a clear sign of a very powerful cyclone. The storm barely moved, drifting at 1–2 knots over exceptionally warm waters, which allowed it to keep drawing energy from the ocean without interruption.

Global trackers noted that no other 2026 storm had intensified this quickly, making Dudzai stand out even in a busy cyclone year. “Slow-moving, rapidly intensifying storms are among the most dangerous to forecast,” a JTWC meteorologist has said in similar Indian Ocean events, because small errors in track or strength can mean big surprises for ships and remote facilities.

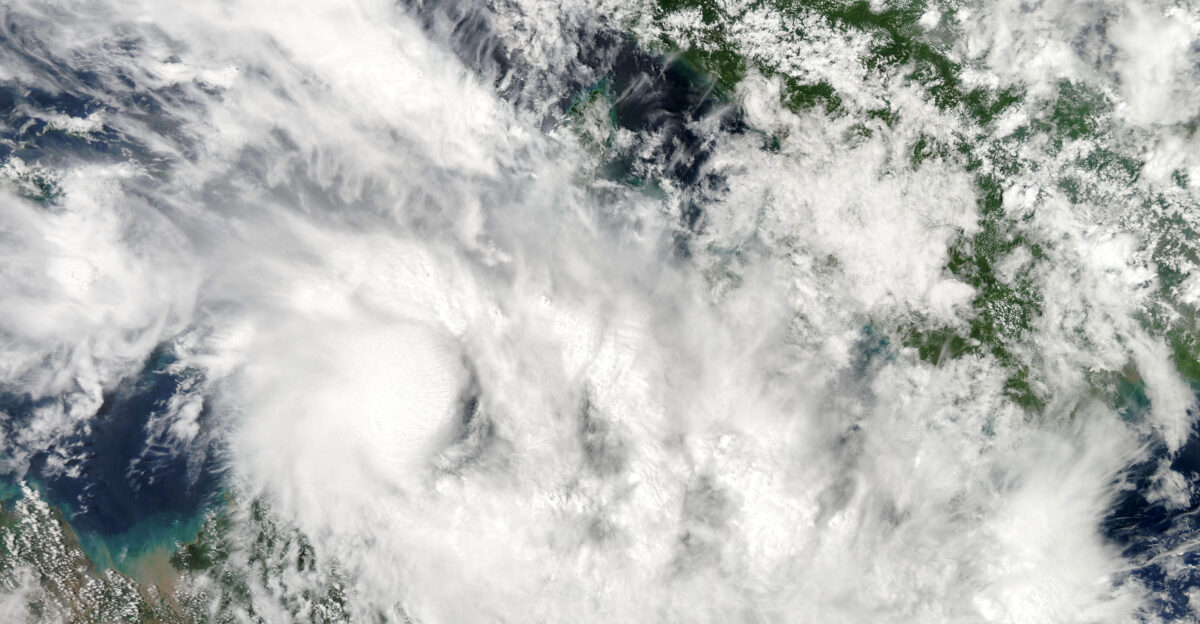

Basin Awakening

Dudzai arrived in a basin that was already awake. The 2025–26 South-West Indian Ocean season sparked early, with systems like Tropical Depression 01 in July 2025 and storms Awo, Blossom and Chenge sweeping through the region. In late December, Intense Tropical Cyclone Grant peaked with 205 km/h winds, brushing St. Brandon and signaling that the basin was primed for strong systems.

After Grant faded, the region quieted briefly before Dudzai formed on January 10 southeast of the Chagos Archipelago, quickly proving it would not be just another mid-season storm. Historical records show that major January cyclones of this strength in the South-West Indian Ocean are rare, making Dudzai a noteworthy outlier in both timing and intensity.

Warm Waters Fuel

Dudzai’s birth followed the classic recipe for a powerful cyclone: warm sea surface temperatures above 26.5°C, low vertical wind shear, and plenty of moisture in the atmosphere. The storm formed roughly 800 km southeast of the Chagos Archipelago, where ocean heat content was high enough to sustain rapid organization from a weak disturbance to a defined tropical depression and then a named storm.

Forecast models quickly picked up the signal that conditions favored further strengthening, and forecasters started flagging the risk that Dudzai could “intensify quickly over very warm water,” a warning often associated with the most dangerous cyclone phases.

Dudzai Unleashed

By January 12, Dudzai had taken the next step: it was classified as an Intense Tropical Cyclone, roughly equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane, with winds near 230 km/h. In global terms, it became the first major cyclone of 2026, no other basin had yet produced a Category 3–5 storm that year, putting Dudzai at the top of the early-season charts.

Data show its winds leapt from about 70 mph to more than 140 mph in roughly a day, a dramatic climb that placed it firmly in the “rapid intensification” category that so worries forecasters. A tropical-cyclone specialist noted that Dudzai “went from a strong storm to a genuine basin benchmark in less than 24 hours,” underscoring the challenge of warning mariners and remote installations in time.

Ocean Threatens

Even without an immediate landfall in sight, Dudzai became a serious ocean hazard as it spun near peak strength. Significant wave heights near the core exceeded 8 meters, and those swells radiated outward for hundreds of kilometers, placing remote atolls and shipping routes inside a broad zone of concern.

Forecast maps showed the storm roughly 1,200–1,300 km from Diego Garcia at peak intensity, close enough that the atoll fell within the outer swell field even if the center stayed far away. The Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS) rated the overall humanitarian impact as low due to the lack of dense coastal populations, but stressed that marine conditions would be “dangerous to very dangerous” along the storm’s path.

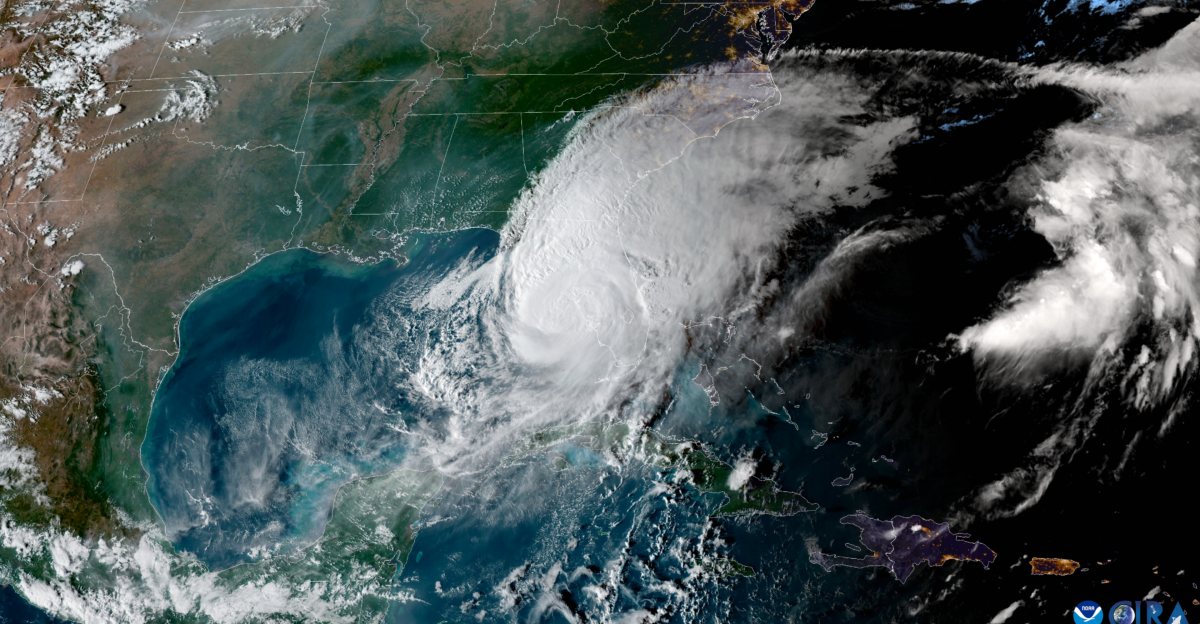

Base On Alert

Diego Garcia, a strategic U.S.–UK military hub in the central Indian Ocean, suddenly found itself inside Dudzai’s broader threat cone. Located more than 1,200 km from the storm’s center, the atoll was never in line for a direct hit, but even distant cyclones can close runways, damage piers and disrupt logistics through powerful swells and gusty squalls.

The base hosts key U.S. Navy and Air Force operations, and analysts have long described it as “vital for America to project power across the Indian Ocean and beyond.” As Dudzai strengthened, standard military weather protocols kicked in: close monitoring of wave forecasts, checks on moorings and fuel lines, and contingency plans for delayed flights or diverted ships.

Swells Pound

While no major population centers lay directly in Dudzai’s path, the storm’s eyewall generated towering seas that spread across busy shipping lanes. GDACS maintained a green (low) alert level for humanitarian impact, but models still projected waves exceeding 8 meters near the core and sending powerful swells toward island groups such as the Chagos Archipelago.

For mariners, those seas meant long detours and tense hours: ships adjusted routes to avoid the worst of the swells, adding time and fuel costs to voyages linking Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Maritime analysts warn that “even a storm that never touches land can rattle global trade when it disrupts a major ocean crossroads,” a description that fits the central Indian Ocean’s role in east–west shipping.

Monitors Activate

As Dudzai doubled in strength, regional and global forecast centers moved into high gear. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center and other agencies began issuing frequent bulletins highlighting the risks of rapid intensification and the uncertainty around the storm’s slow, wobbling track. With no other major storms yet in 2026, Dudzai became a reference system that meteorologists in other basins watched closely, both to refine models and to anticipate similar behavior elsewhere.

Shipping companies started rerouting vessels, and military planners emphasized resilience, keeping critical operations running while staying ready to adjust if the cyclone unexpectedly curved toward more populated or strategic areas.

Warming Trend

Dudzai did not occur in isolation. Season data through mid-January show six systems already in the South-West Indian Ocean, with both Grant and Dudzai reaching peak winds of about 205 km/h but Dudzai dropping to a lower minimum pressure of 937 hPa.

Researchers point out that warmer sea surfaces worldwide are linked with stronger and more rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones, a pattern emerging across several basins including the Indian Ocean. Dudzai’s timing, in the first half of January and its intensity raised particular concern, because powerful storms earlier in the season give less recovery time to coastal and island communities.

Slow Crawl Exposed

One of Dudzai’s most troubling traits was its glacial pace over very warm water. Moving at just 1–2 knots, the cyclone remained parked over seas above 28°C, which helped it maintain Category 4–equivalent intensity longer than many faster-moving storms.

That slow crawl meant the storm kept churning the ocean surface, pumping more energy into long-period swells that could travel great distances and affect remote coasts and atolls. Forecasters also faced a familiar challenge: the longer a strong system lingers, the greater the chance small shifts in steering winds can send it on an unexpected path.

Vigilance Heightens

On Diego Garcia, commanders and support staff shifted into a higher state of watchfulness as Dudzai’s forecast evolved. The base has weathered brushes with storms like Chenge before, but each new cyclone brings its own uncertainty, especially when rapid intensification is involved. Routine turned to readiness: reviewing radar feeds, checking emergency supplies and rehearsing procedures for securing aircraft and small craft if swells or winds worsened.

Internal planning documents from similar events show how strongly the base relies on external agencies for storm data, with one defense analyst noting that “remote outposts live and die by good forecasts when the ocean turns hostile.”

Track Shifts

As more data came in, forecast models gradually nudged Dudzai’s projected track farther southwest, away from Grant’s earlier path and easing the immediate pressure on Diego Garcia. Islands such as Rodrigues and Mauritius kept a close eye on the evolving cones but were spared direct, close-range impacts as the storm curved over open water.

Forecasters at regional centers refined their models in real time, adjusting for wind shear and other atmospheric changes that could weaken or deflect the cyclone. The experience reinforced the need for tight coordination among agencies, because even small track adjustments can alter who faces dangerous seas or storm-force winds.

Resilience Tested

For Diego Garcia and other remote infrastructure in the central Indian Ocean, Dudzai served as a live stress test. Crews reinforced docks, secured equipment vulnerable to high waves and prepared backup plans for supply chains in case flights or ship movements had to be halted. Defence materials highlight how, after previous storms, the base invested in stronger moorings and higher safety standards, steps analysts have praised as “essential for keeping a remote hub functioning through repeated climate shocks.”

Dudzai ultimately did not breach those defenses, but its long-lasting swells and unpredictable strength emphasized gaps in rapid-intensification alerts and the need for constant updates. Operations gradually returned to normal, but with fresh lessons logged for the next cyclone.

Experts Caution, Future Fury?

As Dudzai weakened, the debates began. Some experts argued that forecast models still underestimate rapid intensification in parts of the Indian Ocean, especially when storms form over deep pools of warm water. Insurers and markets, watching from afar, noted the broader uncertainty as a risk factor even when a storm misses major land areas.

GDACS’ low-impact rating proved accurate for direct human losses, but specialists warned that remote bases, supply chains and marine ecosystems bear costs that are harder to measure. With the 2025–26 season not due to end until April 30, scientists caution that Dudzai may be a preview rather than an exception.

Sources:

Wikipedia, 2025–26 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season, 23 November 2023

GDACS, Overall Green alert Tropical Cyclone for DUDZAI-26 – in Mauritius, 12 January 2026

GDACS, Overall Green alert Tropical Cyclone for DUDZAI-26 – GDACS Meteo Report, 9 January 2026

Walter C. Ladwig III, Diego Garcia and the United States’ Emerging Indian Ocean Strategy, Autumn 2010

Walter C. Ladwig III, Diego Garcia and American Security in the Indian Ocean, 2014

Wikipedia, Tropical cyclones in 2026, 2 January 2026