In the frigid depths of the Greenland Sea, nearly 12,000 feet beneath Arctic ice, scientists uncovered an extraordinary world in May 2024. A remotely operated vehicle plunged into uncharted territory on the Molloy Ridge, revealing the Freya Hydrate Mounds—the deepest known methane cold seeps ever found, teeming with life sustained by ancient chemical energy.

Methane Seepage at Record Depths

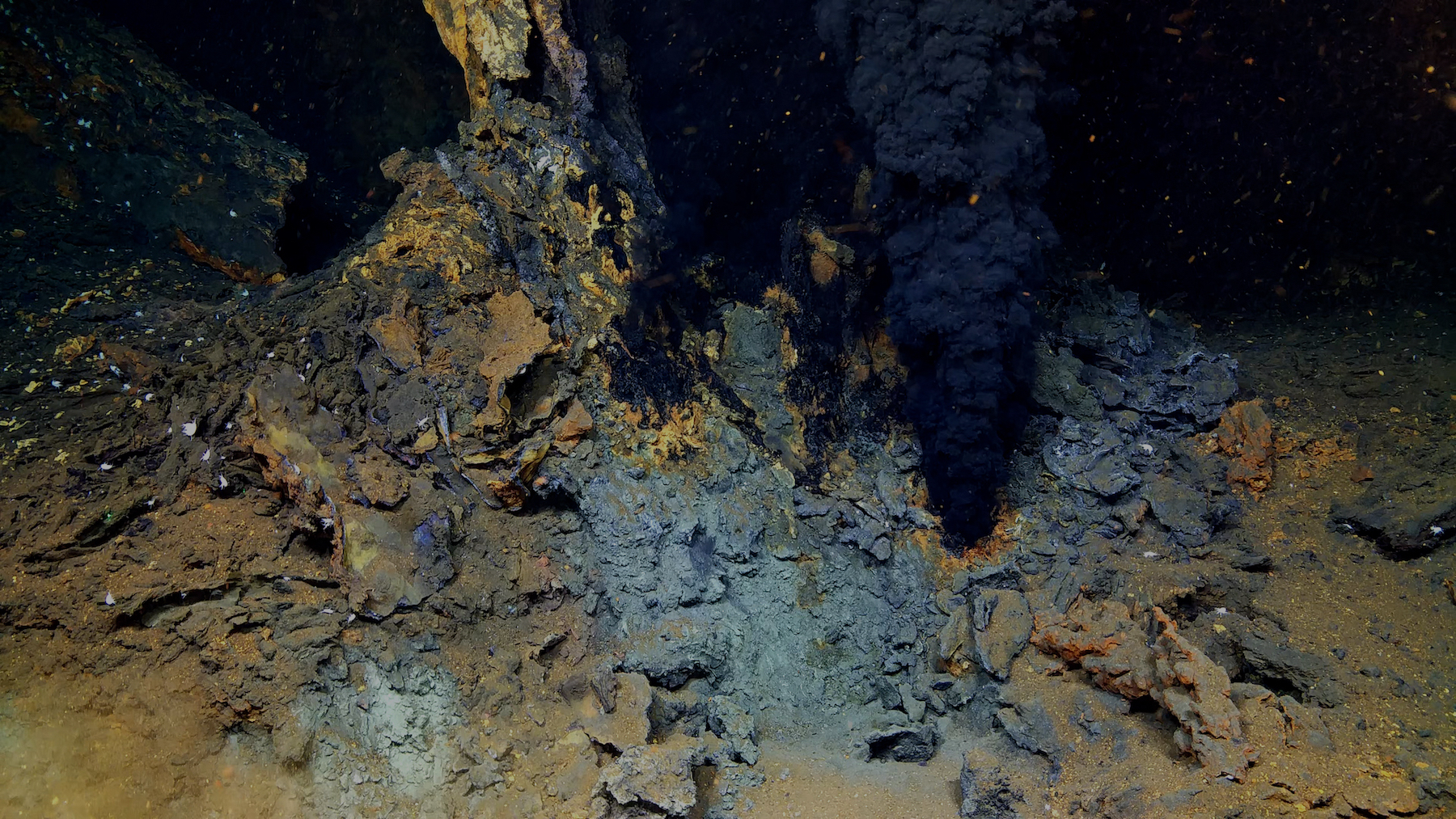

At 3,640 meters, continuous methane leaks from the seafloor form massive frozen gas hydrates, some spanning 6 meters across. These cone-shaped mounds, marked by collapse features, create structured habitats unlike the sparse deep-sea floors researchers typically encounter. Sonar detected methane-rich plumes rising over 3,300 meters—the tallest recorded worldwide—carrying thermogenic methane and traces of crude oil from deep sediments. This pushes the known depth limit for such systems nearly 1,800 meters deeper than previous finds above 2,000 meters.

Ancient Origins Fuel Modern Life

The methane traces back to Miocene sediments, holding carbon locked away millions of years ago, long predating human influence. Slow tectonic shifts and fluid dynamics drive this release, making Freya a snapshot of deep geological time intersecting with today’s active processes. The expedition’s advanced tools captured hydrate formation, destabilization, and collapse in real time, underscoring the site’s dynamism amid warming oceans that could accelerate global hydrate instability.

Expedition Targets Extreme Frontiers

The Ocean Census Arctic Deep EXTREME24 mission united 36 scientists from 15 institutions in the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard. Led by Giuliana Panieri of UiT The Arctic University of Norway, the team deployed Aurora, an ROV rated for 6,000 meters, to map and sample this hostile realm of darkness, crushing pressure, and near-freezing water. Their cross-disciplinary approach yielded detailed geochemical data, imagery, and seafloor maps, confirming Freya’s biological richness and geological activity.

Thriving Chemosynthetic Ecosystem

More than 20 faunal species clustered densely on the mounds, including vast forests of siboglinid tubeworms, grazing snails on bacterial mats, and scavenging amphipods. Under 365 atmospheres of pressure in water just above freezing, these organisms rely on chemosynthesis: bacteria oxidize methane and hydrogen sulfide, providing energy that tubeworms host as symbionts. This self-sustaining food web mirrors communities at nearby hydrothermal vents like Jøtul at 3,020 meters, hinting at broader connectivity across energy sources and challenging models of isolated deep habitats. Genetic analysis revealed ancient lineages, active reproduction, and juvenile forms, signaling robust populations.

Climate Risks and Policy Crossroads

As plumes ascend through oxygen-rich waters, bacteria convert much methane to carbon dioxide, fueling acidification, though some may reach the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than CO2 per molecule. Freya’s position on the Molloy Ridge overlaps Norway’s seabed mineral exploration zones, opened in early 2024 but paused amid outcry. By December 2024, the government extended the licensing halt until at least 2029 and slashed funding for mineral mapping, influenced by over 40 countries and 1,000 scientists advocating moratoriums. Acoustic data suggest more deep seeps nearby, amplifying stakes for biodiversity, carbon cycling, and industrial threats. Peer-reviewed findings in Nature Communications on December 17, 2025, highlight Freya as a vulnerable oasis, where advancing climate shifts and resource demands test the balance between preservation and exploitation.

These discoveries illuminate hidden Arctic vulnerabilities, urging swift safeguards to protect irreplaceable ecosystems before warming or extraction alters them irrevocably.

Sources

Deep-sea gas hydrate mounds and chemosynthetic fauna discovered at 3640 m on the Molloy Ridge, Greenland Sea. Nature Communications, December 17, 2025

Deepest gas hydrate cold seep ever discovered in the Arctic at 3,640 m depth. Phys.org, December 22, 2025