For over a century, scientists have grappled with the mysterious origins of Earth’s earliest animals, a puzzle that continues to challenge our understanding of life’s beginnings.

Despite genetic and chemical clues pointing to animal life over 650 million years ago, the oldest fossils only appear around 543 million years ago.

This 100-million-year gap between evidence and fossil records has left experts questioning long-held assumptions about the timelines of life’s dawn. What did this discovery reveal about the accuracy of our dating methods? The answers might surprise you.

Timeline Clash

Molecular clocks extracted from living sponge species suggested animal emergence occurred before 650 million years ago. Chemical rock signals and biomarker evidence corroborated this timing, but no hard fossils supported these ancient dates.

Fierce debates raged in paleontology laboratories across Europe and beyond, with researchers struggling to reconcile competing datasets.

This escalating pressure fundamentally challenged existing evolutionary models and compelled scientists to reassess the accuracy of molecular dating.

Fossil Blind Spot

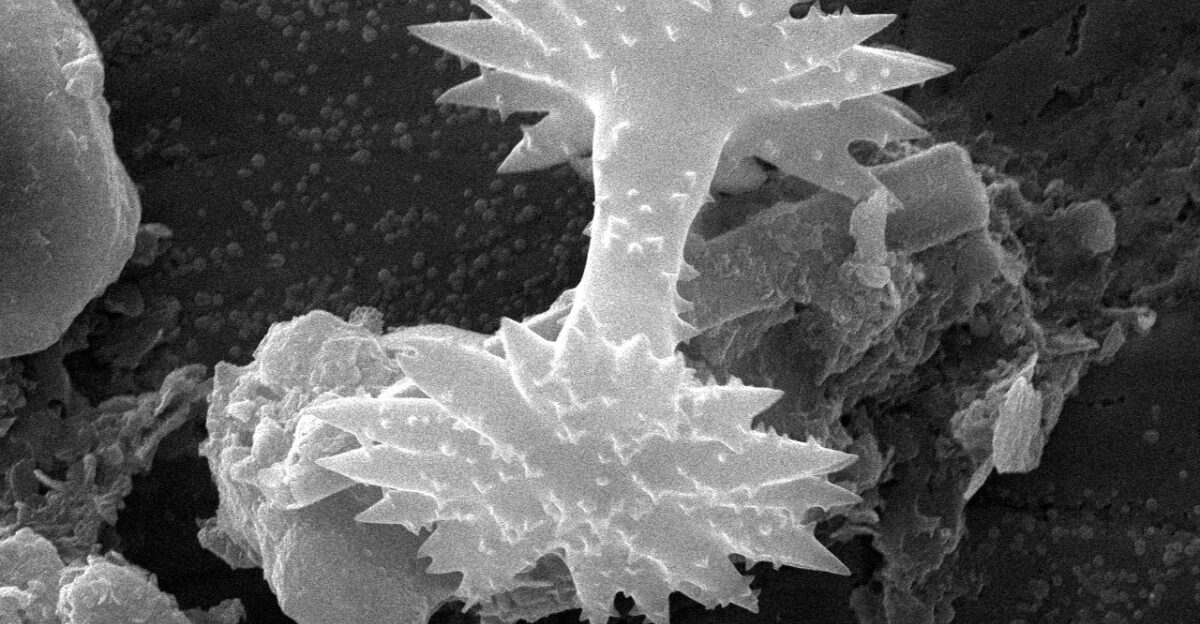

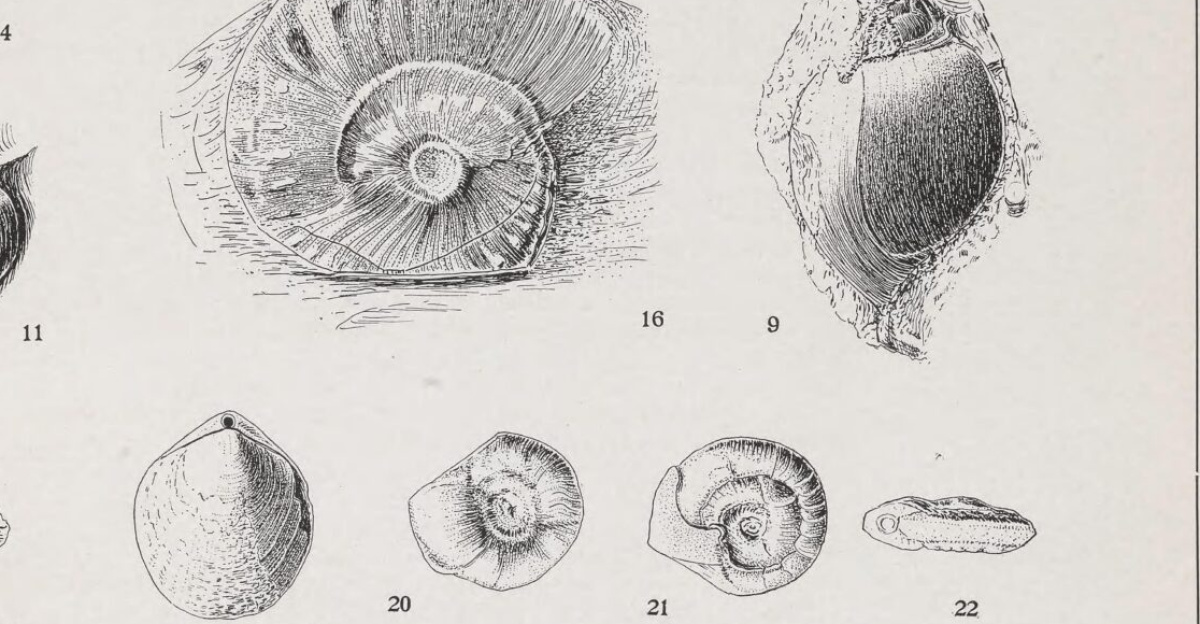

Sponge spicules—tiny, glass-like skeletal needles—fossilize exceptionally well and appear abundantly in late Ediacaran rocks dating to around 543 million years ago.

However, earlier rock layers from the 600-615 million-year-old period remained mysteriously silent, containing no evidence of spicule fossils. Bristol researchers noted that the presence of mineralized skeletons in all living sponges fueled broad scientific assumptions about ancient ancestors.

These assumptions masked the true origins of sponges and created the interpretive blind spot in paleontological understanding.

Genetic Pressures

Comprehensive studies analyzing 133 protein-coding genes generated data clashing dramatically with sparse and fragmentary fossils in the geological record.

International teams of researchers worked intensively to reconcile the two conflicting datasets and evidence sources. Ediacaran-era rocks collected from global sites held only ambiguous traces and insufficient fossilized remains.

This conflict tightened the urgent scientific quest to determine precisely when early animals truly began diversifying into distinct lineages and ecological roles.

Soft Sponge Reveal

A University of Bristol-led research team, headed by Dr. M. Eleonora Rossi, successfully dated Earth’s first sponges to between 600 and 615 million years ago, publishing their groundbreaking results in Science Advances.

The team’s key discovery revealed that these earliest sponges were soft-bodied creatures, completely lacking mineralized skeletons—finally explaining the mysterious 100-million-year fossil gap.

Their comprehensive analysis merged genetic data from modern organisms with fossil evidence using sophisticated Markov statistical models, bridging two previously conflicting datasets into a coherent timeline.

Ediacaran Impact

The Bristol team’s findings fundamentally reshape scientific understanding of the Ediacaran Period and its ancient marine environments. These soft-bodied sponges effectively filled the mysterious 100-million-year void that existed before the subsequent Cambrian Explosion, when complex life rapidly diversified.

The absence of mineralized spicules meant these earliest sponges left no fossilized remains to preserve, essentially becoming invisible to traditional paleontological methods.

This discovery alters ocean ecosystem timelines worldwide and provides crucial context for understanding early animal evolution and ecological development.

Rossi’s Insight

Dr. M. Eleonora Rossi, Honorary Research Associate at the University of Bristol, provided critical insight into the paleontological mystery: “Our results show that the first sponges were soft-bodied and lacked mineralized skeletons.

That’s why we don’t see sponge spicules in rocks from around 600 million years ago—there simply weren’t any to preserve.”

Her words clarify why early sponge life evaded permanent stone records and illuminate a fundamental principle about fossil preservation and what can be detected in geological strata.

Skeleton Independence

Dr. Ana Riesgo from Madrid’s Museum of Natural Sciences made a crucial observation about skeletal evolution: spicules evolved completely independently across different sponge lineages, with calcite structures forming in some species and silica in others through distinct genetic pathways.

This remarkable convergent evolution, where different organisms independently evolved similar structures, challenges single-origin theories about sponge skeleton development.

The discovery significantly affects how paleontologists and evolutionary biologists interpret fossil patterns globally and understand the mechanisms driving skeletal innovation.

Markov Modeling

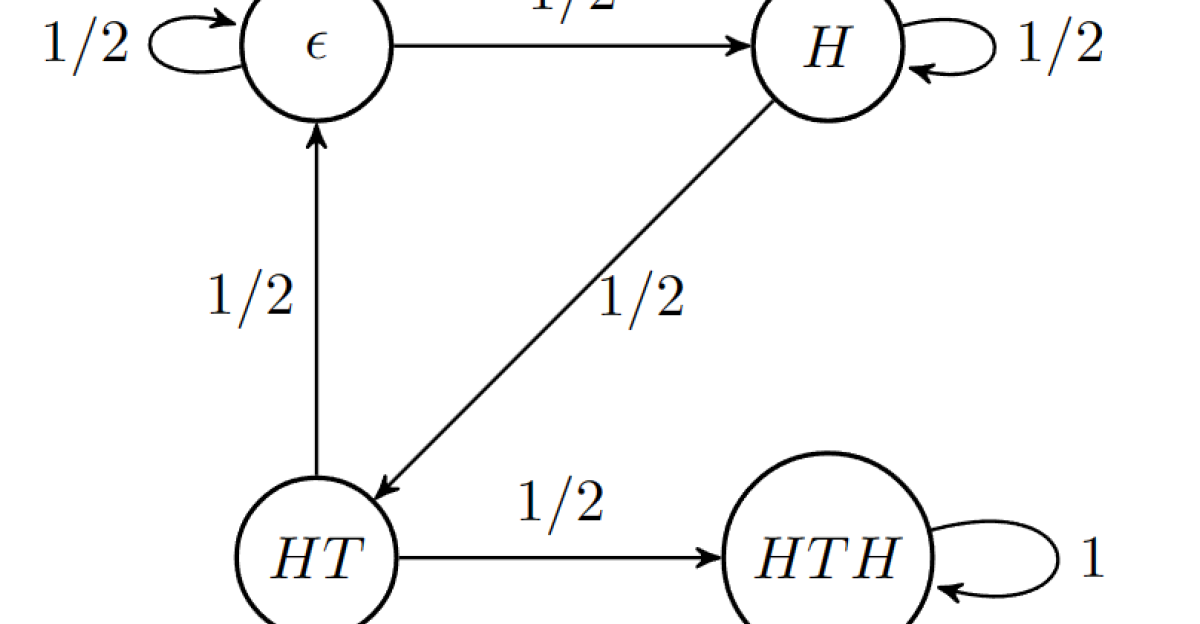

Dr. Joseph Keating, a key methodologist on the Bristol team, explained their revolutionary statistical approach: “We used a Markov process, a type of predictive model commonly used in mathematics and statistics, for modeling transitions between different skeletal types.”

Their sophisticated models rejected early hypotheses of mineralized sponges, confirming the soft-body theory.

Published in Science Advances in January 2026, this innovative statistical tool successfully bridges biological evolution and deep-time analysis, offering a new methodological model for paleontological research.

Reef Foundations

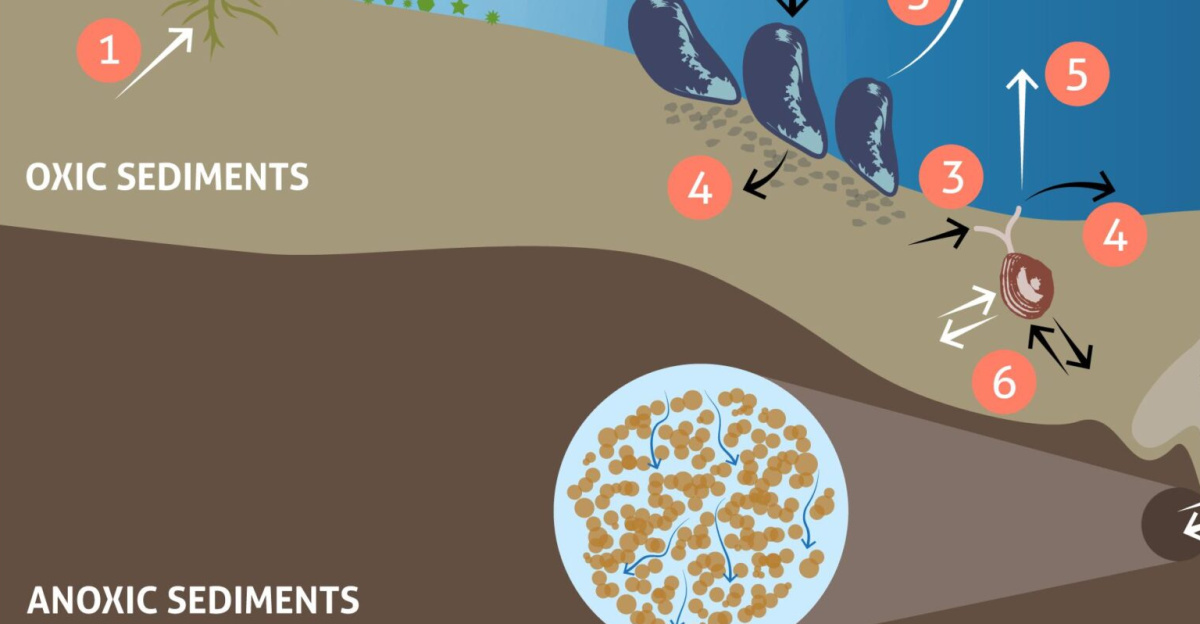

Sponges pioneered reef-building ecosystems and co-evolved dynamically with Earth’s complex biological and chemical systems over hundreds of millions of years.

Professor Davide Pisani at the University of Bristol emphasizes sponge origins as crucial for understanding all subsequent animal evolution, including humans and our evolutionary ancestors.

These soft-bodied sponges drove unseen diversification in early oceans despite leaving no fossils, fundamentally reshaping planetary nutrient cycles, carbon sequestration, and ecological interactions from the Ediacaran Period onward.

Remaining Questions

Professor Phil Donoghue, a respected Bristol palaeobiologist, noted that early sponge diversification proceeded without mineralized spicules—raising the persistent question: what specifically fueled this initial evolutionary radiation?

The team’s findings successfully explain when early sponges originated and what physical characteristics they possessed, but the underlying biological and environmental drivers behind their initial diversification remain “a tantalizing mystery.”

This unresolved question highlights gaps in current understanding and points toward exciting directions for future paleontological research and discovery.

Leadership Vision

Dr. Rossi’s University of Bristol research team significantly advances the field of phylogenomics—the integration of evolutionary genetics with fossil data.

Professor Pisani emphasizes how sponge origins provide crucial insights for understanding how all subsequent animals evolved from these earliest ancestors.

The study strategically repositions the University of Bristol as a major international player in resolving century-old scientific debates about when life’s earliest complex forms first appeared and how they evolved into modern animals.

Strategic Advances

The Bristol team’s innovative gene-fossil fusion methodology establishes an important new scientific model for addressing disputed evolutionary timelines across all fields of paleontology.

Future research expeditions will target 600-million-year-old rock formations, specifically searching for preserved soft tissue traces and fossilized remains.

These investigations will employ sophisticated biomarker analysis techniques to complement and extend traditional fossil records, potentially revealing additional evidence about early animal evolution in sedimentary deposits worldwide.

Skeptic Outlook

Some paleontologists point to biomarker evidence suggesting even earlier pre-635-million-year-old sponge origins, citing debated sterol molecular signatures preserved in ancient rocks.

Experts like Dr. Riesgo acknowledge that independent skeletal evolution is plausible based on current genetic data, while urging comprehensive analysis of wider genomic datasets from diverse sponge species.

The Bristol study successfully narrows the gap between molecular clocks and fossils, but doesn’t completely settle all remaining timeline debates within the paleontological community about exact origin dates.

Future Horizons

Researchers now face compelling questions about whether soft-sponge models can predict triggers for the subsequent Cambrian Explosion’s rapid diversification.

The Bristol team plans to investigate how ocean chemistry fundamentally shifted during this period and influenced animal evolution.

A critical open scientific question remains: did nutrient flux variations and oxygen level changes in ancient oceans spark subsequent animal diversification independent of skeleton development, or did other environmental factors drive this evolutionary radiation?

Research Impact

The study’s findings, published in Science Advances, contribute substantially to deepening scientific understanding of early animal evolution and the biological origins of modern biodiversity.

The research demonstrates conclusively how combining molecular genetics, chemical analysis, and fossil evidence through sophisticated statistical modeling can resolve long-standing scientific controversies and close apparent gaps between different dating methodologies and evidence sources.

Global Collaboration

Dr. Ana Riesgo from Madrid’s Museum of Natural Sciences and the University of Bristol’s international research team extend research impacts across multiple continents and institutions.

Multiple independent research groups worldwide are now actively reassessing animal origin timelines based on the soft-body hypothesis and the Bristol methodology.

These collaborative international redating efforts promise to reshape understanding of when early animals first diversified and established the ecological foundations for all subsequent animal life on Earth.

Environmental Ties

Early sponges actively cycled silicon and carbon through Ediacaran oceans, participating in complex biogeochemical processes.

These soft-bodied sponges altered seafloor ecosystems without producing mineralized spicules, directly influencing ancient paleoclimate models and oxygen cycling.

The study’s findings refine scientific understanding of deep-time ecology and complex biogeochemical cycles operating during the Ediacaran Period, revealing how microbial and early animal communities interconnected with Earth’s evolving chemical and physical environment.

Evolutionary Significance

Identifying sponges as Earth’s first animals fundamentally reframes the animal tree of life and our position within evolutionary history.

This groundbreaking discovery definitively places animal origins firmly within the Ediacaran Period, well before the subsequent Cambrian Explosion, establishing a new scientific baseline for understanding evolutionary complexity and how life diversified.

The findings demonstrate that animals originated earlier than fossil records previously indicated, reshaping how paleontologists interpret the complete history of life.

Scientific Resolution

This comprehensive research successfully resolves the century-old fossil record gap by revealing soft-bodied animal origins, demonstrating the profound power of integrating genetic analysis, chemical evidence, and paleontological data through rigorous statistical methodology.

The findings effectively align molecular clocks with fossil records, closing what appeared to be an irreconcilable scientific debate.

This breakthrough exemplifies how modern science bridges multiple disciplines to solve deep mysteries about Earth’s ancient history and the origins of life.

Sources:

SciTechDaily Jan 2026

Phys.org Jan 2026

Earth.com Jan 2026

Science Advances Jan 2026

University of Bristol Jan 2026