On January 4, 2026, Ukrainian forces recovered something they had never seen before. In the snow of the Chernihiv region, a Russian Shahed-136 drone lay intact—its warhead replaced by a shoulder-fired air-defense missile.

This was no longer a one-way bomb. It was a loitering aerial ambush platform. For the first time, a mass-produced kamikaze drone had the ability to shoot back at the aircraft sent to destroy it.

The Discovery That Alarmed Ukraine’s Air Defenders

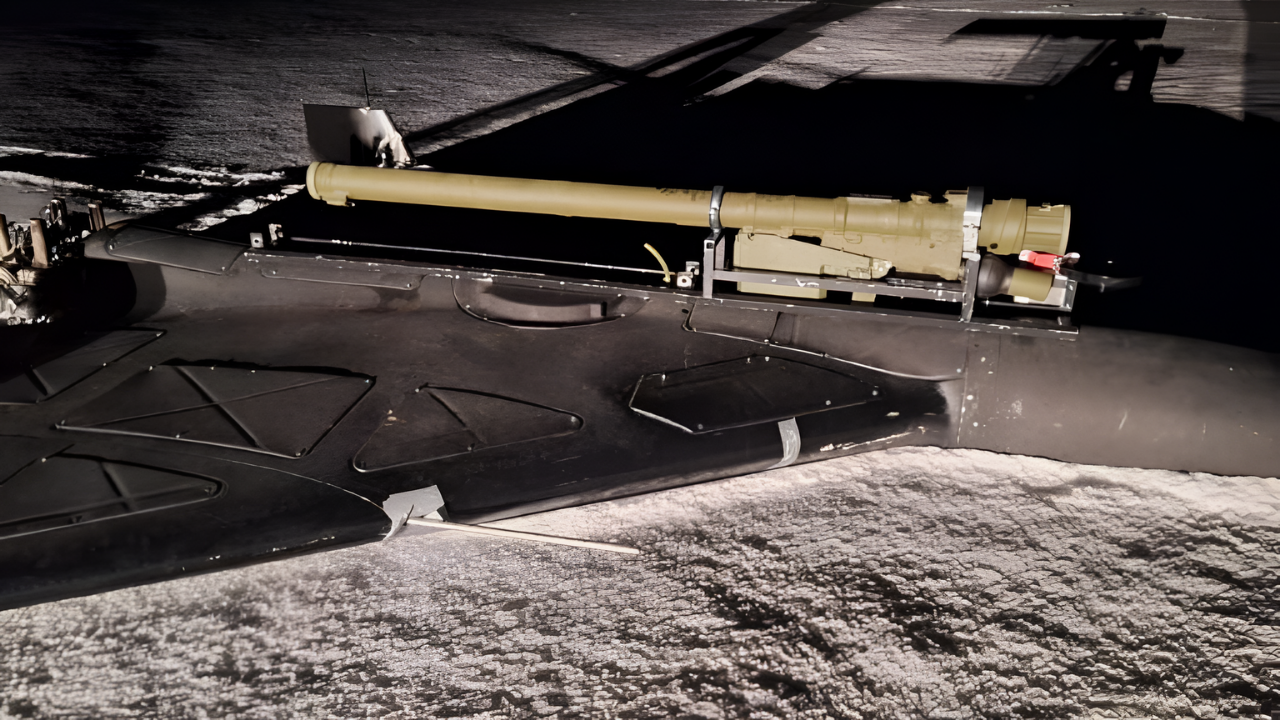

The drone was recovered by Darknode Battalion of the 412th Nemesis Brigade within Ukraine’s Unmanned Systems Forces. Because the drone came down intact, engineers were able to fully examine the system.

What they found confirmed a major escalation: a MANPADS mounted directly on top of the drone, complete with camera, radio modem, and remote launch capability—transforming interception missions into lethal gambles.

From Suicide Drone to Air-to-Air Hunter

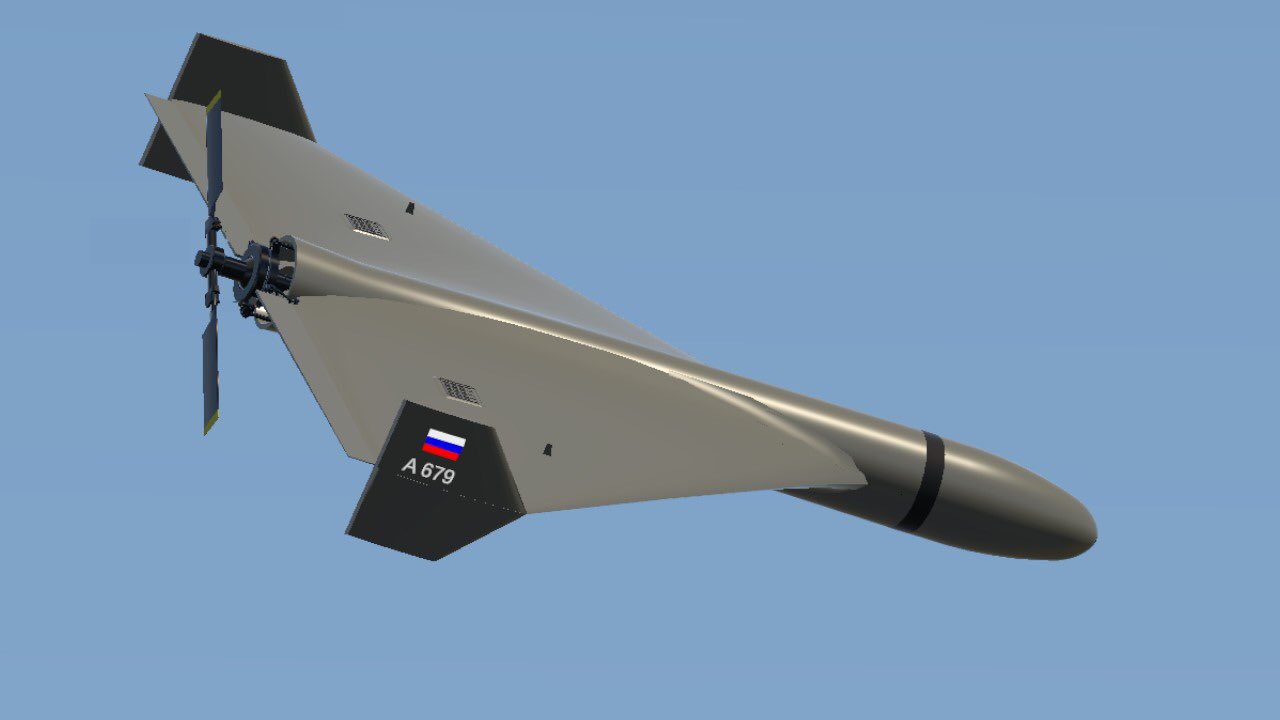

The Shahed-136, known in Russia as the Geran-2, was designed as a cheap, autonomous strike weapon. This version breaks that mold entirely.

The mounted missile—either an Igla-S or possibly a Verba—gives the drone a six-kilometer engagement range and the ability to threaten helicopters and jets mid-mission. The Shahed is no longer just something to shoot down. It is something pilots must now fear.

Why MANPADS Change Everything

Unlike heavier air-to-air missiles tested earlier, MANPADS weigh roughly 40 pounds in their launch tube—less than half the mass of the Soviet-era R-60 previously seen on drones.

That weight reduction allows simpler mounting, better endurance, and fewer aerodynamic penalties. Crucially, modern seekers—especially the Verba’s multispectral system—reduce the need to point the entire drone directly at a target, making ambush tactics far more practical.

How the Missile Is Fired

This is not an autonomous kill system. A human operator remains in the loop. The drone transmits live video via radio or cellular networks. Once the seeker locks on, a signal is sent back.

The operator—often located deep inside Russian territory—makes the final decision to fire. From detection to launch, the window can be just seconds. It is remote warfare distilled to its most impersonal form.

The Immediate Warning to Ukrainian Pilots

Within hours of the discovery, Ukrainian helicopter crews were warned to avoid head-on approaches to Shahed drones.

Circular or loitering flight patterns were flagged as especially dangerous. Intercepts that once relied on close-range cannon fire now carry missile risk. Every engagement must assume the drone can retaliate. The safest tactics are now also the least efficient—allowing more drones to slip through to civilian targets.

Why Russia Is Doing This Now

Ukraine has become highly effective at hunting Shaheds. Armed helicopters, fighters, and interceptor drones have destroyed thousands. Russia’s response is deterrence.

By arming even a small percentage of its monthly output—2,700 combat Shaheds plus 2,500 decoys—it forces Ukrainian pilots to slow down, back off, or abort missions. The missile doesn’t have to fire to succeed. Its presence alone reshapes behavior.

A Dangerous Cost Inversion

The economics are brutal. A disposable drone costing tens of thousands of dollars now threatens aircraft worth tens of millions. Ukraine’s Western-supplied F-16s spend roughly 80% of their missions hunting drones, often using guns to conserve missiles.

Adding air-to-air capability to Shaheds turns those patrols into high-risk operations—where a slow, subsonic platform can end a pilot’s life in seconds.

The Human Cost Already Paid

Ukraine has already lost five aircraft intercepting Shaheds since 2022—before missiles were added. Among them was Lt. Col. Maksym Ustymenko, killed in June 2025 after shooting down seven drones in one mission.

He guided his damaged F-16 away from civilians and had no time to eject. Missile-armed Shaheds increase the danger for pilots already flying the most perilous missions of the war.

How This Compares to Earlier Experiments

In December 2025, Ukraine intercepted a Shahed armed with a Soviet R-60 missile. That configuration was heavy, complex, and inefficient. It required pylons, launch rails, and precise drone orientation.

The MANPADS variant is simpler, lighter, and more scalable. It represents refinement—not experimentation. Two months later, Russia has clearly moved on from prototypes to something closer to a deployable concept.

Control Networks Are Expanding

Early Shaheds were autonomous. Today’s versions are not. Russian drones increasingly use line-of-sight antennas, mesh networks, and even Starlink terminals to extend control range.

This enables true man-in-the-loop loitering—something closer to a slow, unmanned fighter than a disposable bomb. As control improves, reaction times shrink, and electronic-warfare advantages begin to erode.

Infrared Countermeasures Add Another Layer

Recent Geran-2 variants have been spotted with electrically heated infrared emitters on their tail assemblies. These generate false heat signatures designed to confuse interceptor drones and heat-seeking missiles. Ukrainian experts have described them as infrared “searchlights.”

Combined with MANPADS seekers that already resist flares and decoys, the drone becomes harder to kill and more dangerous to approach.

A Pattern in Modern Warfare

This escalation mirrors Ukraine’s own breakthroughs. In 2025, Ukrainian drones achieved the first confirmed drone-on-helicopter kills in flight—using platforms costing around $1,000.

That success shocked Russia. The response was inevitable. Asymmetric warfare rewards whoever adapts fastest. Today, drones hunt helicopters. Tomorrow, helicopters must hunt drones that hunt back.

Why the Deterrent Works Even Without Kills

No confirmed Ukrainian aircraft has yet been shot down by a missile-armed Shahed. That may not matter. The deterrent effect is already real. Pilots must assume every drone is armed.

Engagement distances increase. Interception rates fall. More Shaheds reach their targets. In modern warfare, forcing hesitation can be as effective as pulling the trigger.

The Future of Air Combat Has Shifted

The Shahed’s evolution marks a permanent change. Drones are no longer single-purpose weapons. They are modular, networked platforms capable of surveillance, strike, and air defense at once. Doctrine will lag behind reality. Adaptation will decide survival.

Twenty-three years after the first drone-versus-aircraft duel in 2002, the roles have reversed—and the sky is now crowded with hunters that were never meant to fly home.

Sources:

“Russia Adds Anti-Aircraft Missile Capability to Shahed One-Way Attack Drones.” Flight Global, 5 Jan 2026.

“Russian Shahed-136 Kamikaze Drones Now Carrying MANPADS Missiles.” The War Zone, 4 Jan 2026.

“Ukrainian F-16 Pilot Maksym Ustymenko Killed While Repulsing Record Russian Aerial Attack.” Ukrainian World Congress, 29 Jun 2025.

“Ukraine Downs Russian Mi-8 Helicopter With Deep Strike Drone for First Time, Military Claims.” Kyiv Independent, 22 Nov 2025.