A fossil plant smaller than a fingernail, collected more than a century ago from a Scottish rock bed, is reshaping the story of how Earth’s first plants rose from ground-hugging mats to upright forms that eventually supported forests. Using modern laser imaging, researchers have uncovered a transport system inside the 407‑million‑year‑old Horneophyton lignieri that has no parallel in living flora and fills in a long-missing chapter in the evolution of plant vascular tissue.

The Pressure to Grow

Early land plants were tiny, creeping close to the soil surface and lacking the internal plumbing needed to stand tall. Non‑vascular plants such as mosses and liverworts still resemble those pioneers: they do not possess specialized tissues to move water and nutrients efficiently through their bodies, which keeps them small. Later lineages evolved xylem and phloem, the distinct tubes that in modern plants carry water upward and sugars downward, making height and woody stems possible.

How that transition happened has been difficult to reconstruct. Fossils showed a rapid shift in the Devonian period from low, simple plants to species that reached a meter or more in height, but the intermediate steps were unclear. Genetic evidence from living plants added to the puzzle by suggesting that their history was not a simple ladder from “primitive” mosses to more advanced vascular forms. Paleobotanists long suspected that some early species might preserve transitional transport systems, yet the necessary cellular detail had been beyond the reach of earlier microscopes.

Scotland’s Fossil Time Capsule

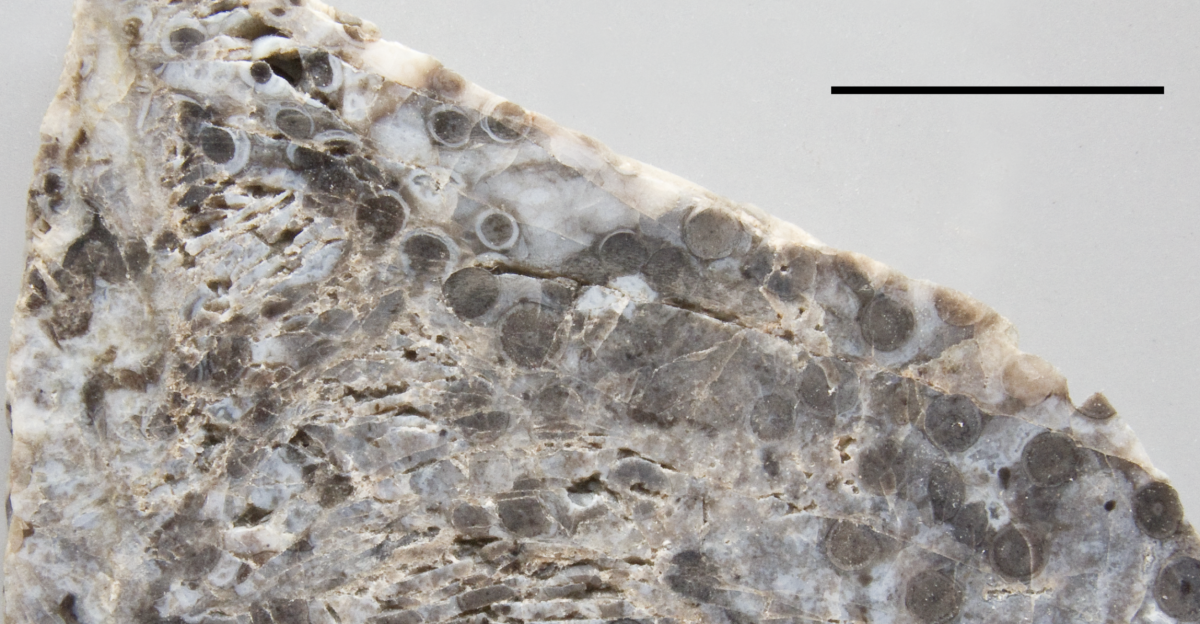

Key evidence comes from the Rhynie Chert in northeastern Scotland, a site that captures an Early Devonian ecosystem in exceptional detail. Around 407 million years ago, silica‑rich hot springs entombed plants, fungi, and other organisms, preserving them down to the level of individual cells. Thin slices of these rocks have been studied for more than a hundred years, revealing the anatomy and growth of some of the first land plants.

Among those specimens was Horneophyton lignieri, a plant that grew to about 20 centimeters and thrived in geothermal wetlands. It was long categorized as a simple early vascular plant, potentially bridging the gap between non‑vascular bryophytes and later, more complex lineages. However, earlier descriptions were based on light microscopy, which could not resolve all of the internal structures. The assumption that Horneophyton possessed standard vascular tissue remained more an inference than a demonstrated fact.

A Fossil Reopened

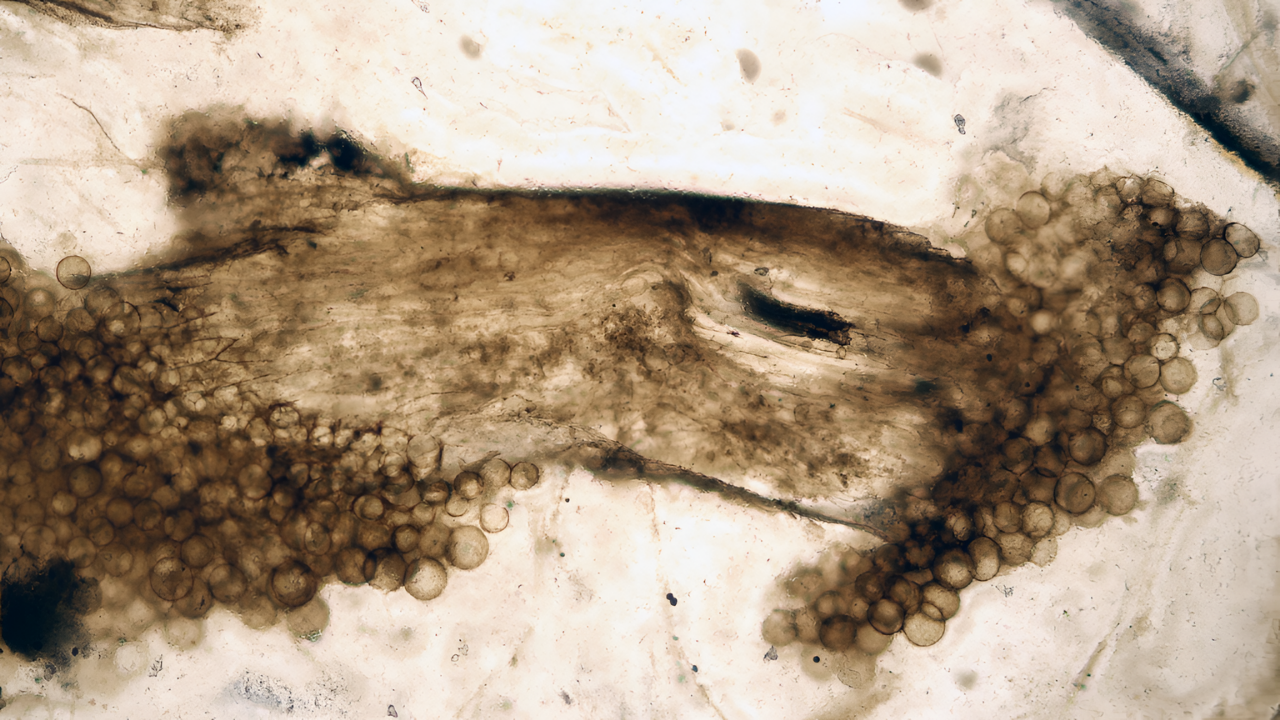

In 2025, researchers revisited Horneophyton using confocal laser scanning microscopy, a non‑destructive method that uses lasers to excite natural fluorescence in fossilized organic matter and build three‑dimensional images layer by layer. This approach allowed scientists to visualize the plant’s internal cells in intact specimens without cutting them into new sections.

The resulting images showed that Horneophyton did not have separate xylem and phloem. Instead, its stems were supplied by a single type of conducting cell known as transfer cells. These cells moved both water and sugars together through the plant, a configuration not seen in any living species. Rather than a simplified version of modern vascular tissue, the team had uncovered a distinct transport strategy that appears to represent a short‑lived evolutionary pathway.

A Short Plant, A Big Shift

For a plant the size of Horneophyton, this unified transport system seems to have been adequate. Water and sugars could circulate through the short stems without major physical limitations. But as plants grow taller, fluid transport becomes constrained by gravity and pressure differences. Separating water and sugar flows into different tissues allows modern plants to regulate pressure and move resources efficiently over greater distances.

Horneophyton’s design likely imposed strict limits on height. Its inability to separate water and sugar transport would have made it difficult to scale up in size, helping explain why it remained small while other lineages eventually experimented with more efficient systems. Nearby in the Rhynie Chert, for example, the plant Asteroxylon evolved distinct xylem and phloem and reached roughly twice the height, hinting at the competitive advantage of that innovation.

Rethinking Early Plant Evolution

The discovery has implications beyond a single species. It supports the view, emerging from molecular studies, that early land plants were already anatomically and genetically complex rather than simple precursors of today’s forms. Bryophytes may not be direct stand‑ins for the first land plants, but specialized survivors with their own evolutionary histories.

Horneophyton shows that plant vascular systems did not emerge through a single, linear series of improvements. Instead, early land ecosystems appear to have hosted multiple “experiments” in internal transport. Some, like Horneophyton’s transfer‑cell network, functioned for small plants but were abandoned as lineages that evolved true xylem and phloem spread, ultimately enabling the rise of forests around 380 million years ago and contributing to major shifts in Earth’s atmosphere and climate.

The revised picture also underscores how much scientific understanding depends on available tools. For more than a century, Horneophyton was variously labeled “proto‑vascular” or “non‑vascular.” The fossil did not change; the resolution of the instruments did. Confocal laser scanning microscopy, alongside techniques such as microCT and synchrotron imaging, is now allowing researchers to extract new information from long‑stored specimens without damaging them.

The work on Horneophyton has prompted calls to systematically re‑examine other Rhynie Chert fossils, and similar sites worldwide, for overlooked anatomical details. Researchers are asking whether Horneophyton’s unusual transport system was unique to one lineage or part of a broader, previously unrecognized phase in plant evolution. Whatever the outcome, the case demonstrates the continuing scientific value of museum collections and suggests that many more “missing pages” in the story of life on land may still be waiting in drawers and cabinets, visible only when old fossils are viewed with new eyes.

Sources

New Phytologist – “Transfer cells in Horneophyton lignieri illuminate the origin of vascular tissue in land plants” – December 17, 2025

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B – “History and contemporary significance of the Rhynie cherts—our earliest terrestrial ecosystem” – December 17, 2017

Plant Molecular Biology – “Deep origin and gradual evolution of transporting tissues: Perspectives from across the land plants” – July 28, 2022

eLife – “An evidence-based 3D reconstruction of Asteroxylon mackiei” – August 23, 2021

Nature Communications – “A fungal plant pathogen discovered in the Devonian age Rhynie chert” – November 30, 2023

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – “The timescale of early land plant evolution” – March 5, 2018