Utah’s Great Salt Lake is famous for its brine shrimp and brine flies, hardy creatures that tolerate extreme salinity. But as lake levels fall toward record lows again, biologists are digging deeper into the lakebed, asking what else might be living out of sight.

Their search, focused on microbialite mounds on the bottom, has revealed a surprising new player in this fragile ecosystem.

Rising Stakes

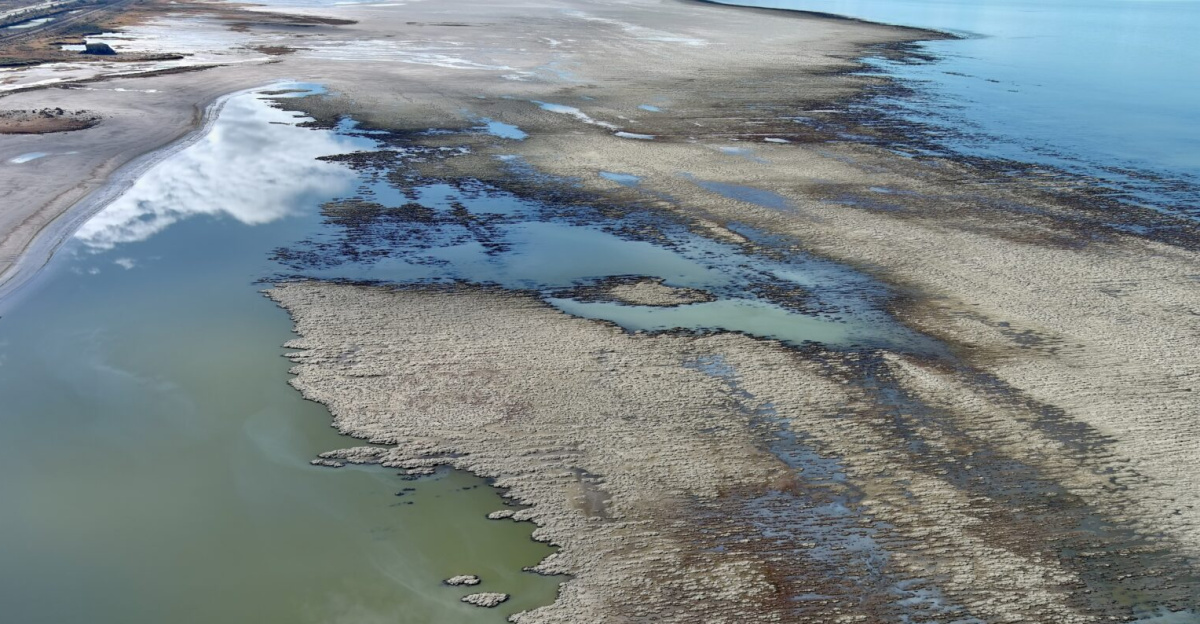

The Great Salt Lake hit a record low in November 2022, when the South Arm dropped to 4,188.5 feet above sea level, and salinity spiked to nearly 19%.

Those conditions pushed brine shrimp and brine flies toward collapse, threatening millions of migratory birds that feed there and alarming Utah officials who depend on the lake for industry and tourism. Scientists warned that unknown organisms might also be at risk.

Harsh Lake History

Great Salt Lake in northern Utah is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the remnant of ancient Lake Bonneville, a vast Pleistocene freshwater lake.

Over thousands of years, climate shifts and water diversions transformed it into a hypersaline basin. For decades, researchers believed only brine shrimp, brine flies, and microbes could survive in its waters, leaving the deeper lakebed largely unexplored.

Mounting Pressures

In recent years, upstream water use, population growth along the Wasatch Front, and persistent drought across Utah have driven lake levels down again.

At 4,192 feet, the state warns of “serious adverse effects” on ecosystems, public health, and the economy, including dust storms from exposed lakebed and stressed wildlife. With levels again near danger thresholds, scientists rushed to document what life the lake still supports.

New Worm Revealed

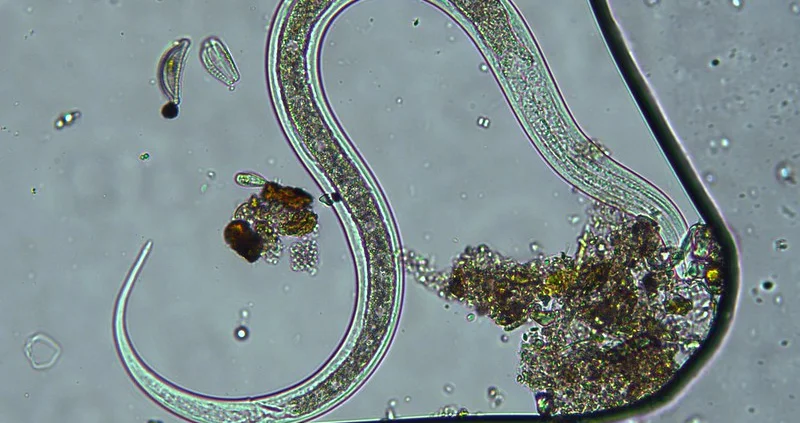

In late 2025, a peer‑reviewed study in the Journal of Nematology formally described Diplolaimelloides woaabi, a new species of microscopic roundworm living in microbialites on the bottom of Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

Led by University of Utah biologist Dr. Michael Werner and co‑author Dr. Julie Jung of Weber State University, the team confirmed over three years that this nematode is new to science and previously unknown in this environment.

Lakebed Habitat

Werner’s team collected sediment from submerged microbialite mounds in Bridger Bay, off Antelope Island in northern Great Salt Lake, between May and October 2024. The site, at about 4,200 feet elevation and salinity around 115 parts per thousand, represents some of the lake’s harshest conditions.

Within the top 10 centimeters of these structures, researchers found thriving populations of the new nematode living “at the bottom” in algal mats.

Human Connections

To name the species, Werner and colleagues consulted elders of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, whose ancestral homelands include the Great Salt Lake region.

The Shoshone suggested “Wo’aabi,” an Indigenous word for “worm,” which became the species epithet woaabi. The collaboration ties modern taxonomy to Indigenous history and acknowledges communities who have long lived around the lake’s shores.

A Marine Lineage

Diplolaimelloides is a genus previously known only from marine and brackish coastal habitats, often associated with algae and sediments in oceans and estuaries. According to the new study and science coverage, D. woaabi is the first documented member of this genus in the United States and the first found in a non‑marine lake.

That makes it a “first of its kind” record for both the country and this inland hypersaline environment.

Expanding Animal Roster

Before this discovery, only two groups of multicellular animals were known to inhabit the lake’s hypersaline waters: brine shrimp and brine flies.

The addition of D. woaabi makes nematodes the third recognized animal group living within the lake itself, reshaping scientific understanding of Great Salt Lake’s biodiversity. Researchers now suspect there may even be a second, as‑yet‑unnamed nematode species present in the same habitat.

Ecological “Mini‑Nugget”

Beyond being new and rare, D. woaabi may play an important, previously unrecognized ecological role. Nematodes in other systems help recycle nutrients by grazing on bacteria. Early observations suggest this species feeds on microbial communities in the lake’s microbialites.

Because only a handful of animals tolerate such conditions, scientists believe changes in this worm’s abundance could serve as a sensitive early‑warning indicator of the lake’s health.

How Did It Get There?

Researchers are debating how an apparently marine‑lineage nematode ended up in a landlocked Utah lake. One hypothesis, described by co‑author Dr. Byron Adams of Brigham Young University, proposes that Diplolaimelloides worms are relics from a time when a shallow seaway covered parts of North America and Utah sat on its shoreline.

As the region uplifted and basins formed, ancestral populations may have been stranded in what became Great Salt Lake.

Bird‑Borne Theory

A competing hypothesis from Werner’s group suggests a more recent arrival. Millions of migratory birds move between saline lakes in the Americas, including sites in South America and Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

Researchers propose that Diplolaimelloides nematodes could have been transported on bird feathers or feet from a coastal or saline habitat elsewhere, then established in the lake’s microbialites. Genetic comparisons with global populations may help resolve the debate.

Sentinel Species Idea

Nematode experts note that when only a few species can persist in an extreme ecosystem, each becomes a powerful “sentinel” for environmental change.

In interviews, Adams and Werner explained that shifts in D. woaabi numbers, distribution, or genetic diversity could reveal subtle changes in salinity, pollution, or nutrient flows well before brine shrimp visibly collapse. That prospect is drawing attention from conservation groups tracking the lake’s decline.

Uncertain Future

While Utah has begun implementing new policy tools and water‑management plans to stabilize the South Arm’s salinity, the lake remains below healthy levels.

Advocacy groups warn that absent stronger conservation measures, Great Salt Lake could again approach or surpass its 2022 record low by 2026. In that scenario, scientists fear a rapid ecological unravelling that might erase D. woaabi before its ecological role is fully understood.

What Comes Next?

Ongoing studies aim to map exactly where D. woaabi occurs around Great Salt Lake, how abundant it is, and what it eats. Researchers are also sequencing its DNA to compare with related species worldwide, looking for clues to its origin and adaptation to extreme salinity.

Those findings could shape future monitoring programs that use the nematode as an official bioindicator of lake health in coming years.

Policy and Science Intersect

Utah lawmakers and agencies are under pressure to balance water deliveries to farms, cities, and industry with the needs of the shrinking lake. Recent legislative changes give officials more flexibility to manage a causeway berm between the lake’s arms, helping control salinity and protect Gilbert Bay’s ecosystem.

As scientists highlight species like D. woaabi, they provide concrete evidence of what may be lost without sustained policy action.

Global Saline Lake Context

Great Salt Lake’s crisis echoes problems at other saline lakes worldwide, such as the Aral Sea and Iran’s Lake Urmia, where shrinking waters devastated wildlife and local communities.

Conservation analysts note that if Utah succeeds in reversing the lake’s decline, it could become a model for protecting saline ecosystems globally. The discovery of a unique nematode adds another reason for international scientists to watch what happens here.

Environmental Health Lens

As water recedes, exposed lakebed can release dust containing arsenic and other contaminants, posing respiratory risks for residents along the Wasatch Front. At the same time, collapsing food webs threaten millions of migratory birds that rely on brine flies, shrimp, and now possibly microbialite‑associated food chains.

Monitoring D. woaabi could help officials gauge when conditions are sliding toward thresholds that endanger both human and ecological health.

Cultural and Artistic Spotlight

Artists and cultural leaders have begun using Great Salt Lake’s plight to spark public conversation. Icelandic‑Danish artist Olafur Eliasson is developing a 2026 sound and light installation in Salt Lake City featuring field recordings from the lake, highlighting its changing wildlife.

Local arts organizations say such projects can connect scientific findings—including new species like D. woaabi—to broader audiences who may not follow technical reports.

Why This Worm Matters

Diplolaimelloides woaabi is microscopic, smaller than a pencil tip, yet it embodies several converging stories: Indigenous knowledge, frontier taxonomy, climate‑driven change, and difficult water choices in the American West.

Its discovery shows that even heavily studied landscapes can still surprise scientists. Whether this newly named animal endures will depend on decisions Utah makes about the lake that is, for now, its only known home.

Sources:

Werner, Michael J., Julie H. Jung, Byron J. Adams, et al. “Diplolaimelloides woaabi sp. n. (Nematoda: Monhysteridae): A Novel Species of Free-Living Nematode from the Great Salt Lake, Utah.” Journal of Nematology, Nov 2025.

“A never-before-seen creature has been found in the Great Salt Lake.” ScienceDaily, 10 Jan 2026.

“Great Salt Lake’s latest species discovery gets a name fit for the lake’s native history.” KSL.com, 13 Dec 2025.

“Great Salt Lake Slips Toward 2022 Record Low.” Grow the Flow Utah, 30 Jul 2025.