Only a few places on Earth create the dense water that fills the deepest parts of the global ocean. This “deep ocean water” powers a vast conveyor of currents that moves heat, oxygen, nutrients, and carbon around the planet.

Scientists often describe it as the ocean’s lungs, quietly ventilating the abyss. New evidence shows one of these critical engines is weakening far faster than expected, raising serious concerns for climate stability and marine ecosystems worldwide.

A Conveyor Under Stress

The most dramatic changes are unfolding not in the North Atlantic, but in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica. Observations and climate models now show a rapid slowdown in Antarctic Bottom Water formation during the modern warming era.

This shift threatens a circulation pattern that remained relatively stable for thousands of years. Scientists warn that once this deep-ocean engine slows, the effects can cascade through the entire global climate system.

Only a Few Factories Exist

Deep ocean water does not form everywhere. According to assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, it is produced in just a handful of regions worldwide. These include parts of the North Atlantic and several zones around Antarctica.

Together, these areas create cold, salty, ultra-dense water that sinks and spreads through the abyss, forming the lower limb of the global overturning circulation linking all major oceans.

How the Deep Is Made

Antarctic Bottom Water forms during brutal winters when sea ice grows rapidly along Antarctica’s coast. As ice forms, it expels salt into surrounding waters through a process called brine rejection.

This makes surface waters heavier until they sink to the seafloor. The process occurs mainly in coastal polynyas in the Weddell Sea, Ross Sea, and select East Antarctic regions, which act as Earth’s primary factories for the densest ocean water.

One Engine Is Failing

Measurements now show a sharp decline in the Weddell Sea, one of the most important Antarctic Bottom Water sources. Since the early 1990s, the volume of newly formed bottom water there has dropped by roughly 30 percent.

This signals a major weakening of a system that once reliably supplied dense water to the global abyss. Warming temperatures and increasing freshwater are preventing surface waters from reaching the density needed to sink.

Just Four Major Sources

Scientists identify roughly four key Antarctic Bottom Water source regions: the Weddell Sea, the Ross Sea, Cape Darnley in East Antarctica, and nearby East Antarctic shelf areas. These few locations feed nearly the entire deep ocean below 4,000 meters.

Because so much of the abyss depends on so few geographic “engines,” even disruption in a single region can have outsized consequences for global circulation and long-term climate regulation.

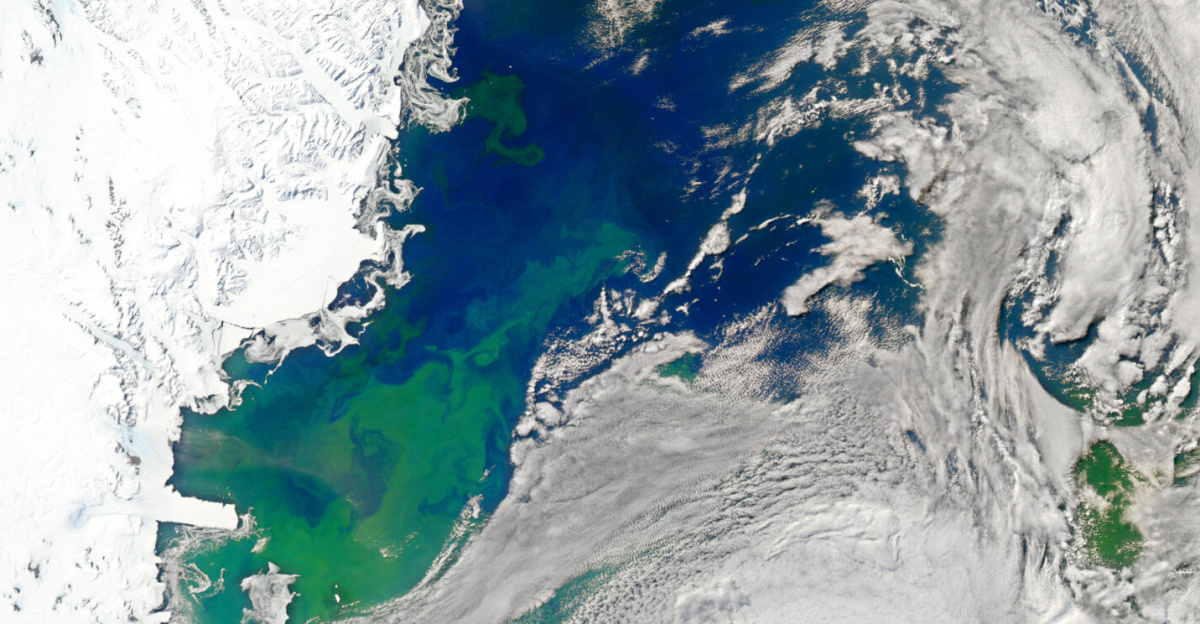

Why Fisheries Care

Deep ocean circulation helps recycle nutrients that eventually return to surface waters, fueling phytoplankton growth that supports marine food webs. This nutrient supply underpins a significant share of global fisheries.

If deep-water formation weakens, fewer nutrients may reach productive surface regions. Over time, that disruption could ripple through ecosystems, affecting fish stocks and coastal communities far from Antarctica, including in the North Atlantic and Pacific.

Climate’s Quiet Shield

The deep ocean has absorbed most of the excess heat generated by human activity, acting as a powerful buffer against rapid atmospheric warming.

It has also taken up a substantial fraction of human-produced carbon dioxide. Antarctic Bottom Water plays a central role in locking that heat and carbon away for centuries. A slowdown in its formation reduces this buffering capacity, leaving more heat and carbon in the atmosphere and upper ocean.

The Freshwater Lid

The main culprit behind the slowdown is freshwater. As the climate warms, Antarctic ice shelves and sea ice melt more rapidly, adding fresh water to the ocean surface.

This lighter water forms a stratified layer that acts like a lid, preventing denser water from sinking. Scientists have linked this increased stratification directly to observed warming, freshening, and reduced transport of Antarctic Bottom Water since the late 20th century.

A Rewired Global Conveyor

Advanced climate models now project that Antarctic overturning circulation could weaken by more than 40 percent by mid-century under high emissions.

That reframes the threat: changes once thought to unfold over millennia may occur within decades. Researchers, including Matthew H. England and Qian Li, warn that such rapid deep-ocean change has little precedent in the modern climate record.

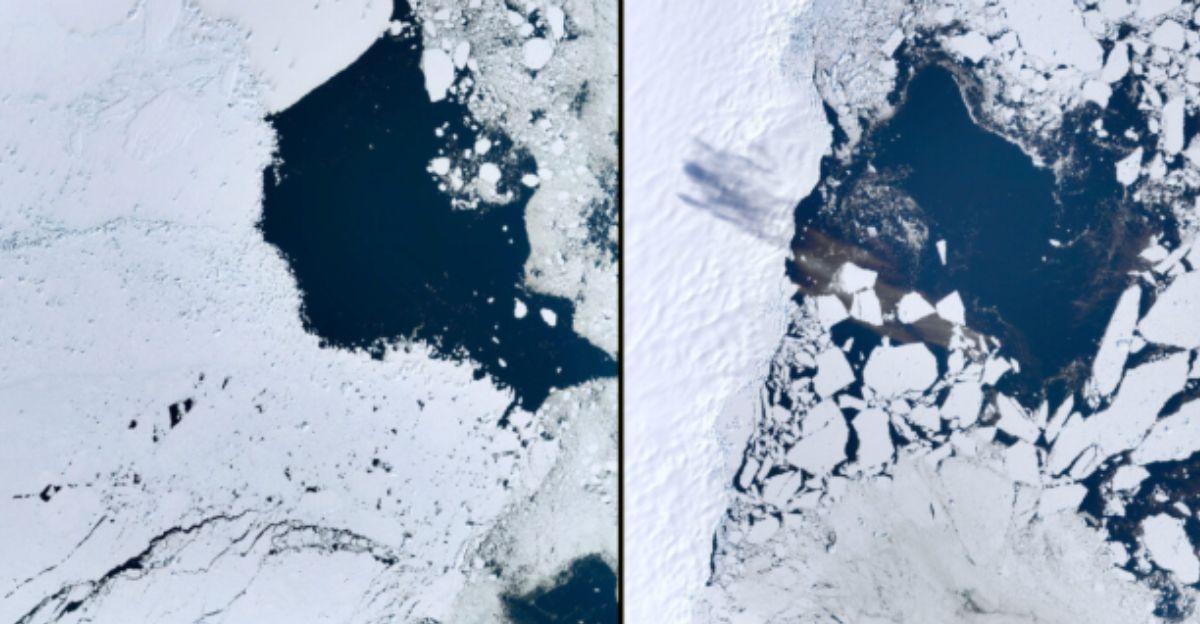

Warning Signs in Ice

Recent events suggest Antarctica’s stability is eroding. The sudden collapse of the Conger Ice Shelf in 2022 followed an extreme warm weather event, demonstrating how quickly conditions can shift.

When ice shelves destabilize, they can rapidly release freshwater into nearby seas. Scientists warn that these abrupt pulses further disrupt dense water formation, making deep-ocean engines once considered resilient increasingly vulnerable to sudden failure.

East Antarctica Reconsidered

East Antarctica was long viewed as the most stable part of the continent. Only in the last decade did scientists confirm regions like Cape Darnley as major contributors to Antarctic Bottom Water.

New modeling suggests warming ocean waters could sharply reduce bottom water formation there as well. Losing this source would remove one of Earth’s few remaining strong deep-water engines, accelerating the slowdown already observed elsewhere.

Pressure on the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is currently one of the largest contributors to Antarctic Bottom Water, supplying an estimated 20 to 40 percent of global production.

Dense water forms near polynyas along the Ross Ice Shelf. However, freshwater from melting ice shelves in neighboring regions can disrupt this process. Continued ice loss in West Antarctica could indirectly weaken this crucial engine over the coming decades.

The North Atlantic Isn’t Immune

Southern Ocean changes are unfolding alongside a documented weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which includes North Atlantic deep-water formation.

Studies suggest this system has slowed by about 15 percent since the mid-20th century. Together, these trends show that multiple deep-water engines across the planet are losing strength during the same warming era, amplifying global climate risks.

Timescales Are Breaking

Deep ocean circulation was once thought to change only over centuries or longer. Yet observed shifts in Antarctic Bottom Water have emerged within just a few decades.

Widespread warming and freshening were detected as early as the 1990s, and projections now point to major circulation changes by mid-century. This compressed timeline challenges long-standing assumptions used in climate, fisheries, and sea-level planning models.

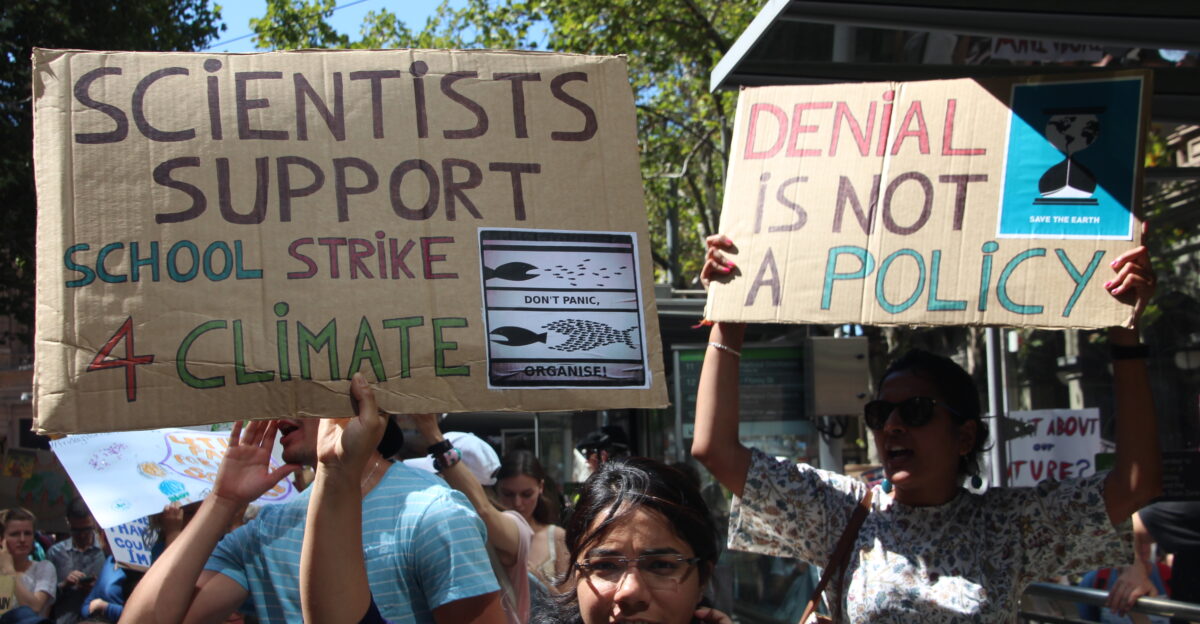

What This Means for Policy

If the deep ocean absorbs less heat and carbon, meeting global climate targets becomes far more difficult. A weaker Southern Ocean sink means a larger share of emissions remains in the atmosphere, requiring steeper reductions elsewhere.

Scientific advisory groups increasingly frame slowing overturning circulation as a systemic climate risk, not a distant or regional Antarctic concern, with direct implications for global mitigation strategies.

Ripple Effects Worldwide

What happens near Antarctica does not stay there. A weaker abyssal circulation can alter global sea-level patterns, regional heat distribution, and large-scale climate systems that influence storms and monsoons.

Because Antarctic Bottom Water ventilates the deep Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans, its decline could affect nations ranging from small island states to major fishing powers across multiple hemispheres.

Feedback Loops Forming

As circulation slows, fewer nutrients may reach surface waters in some regions, reducing phytoplankton growth and weakening the ocean’s biological carbon pump.

That, in turn, limits carbon uptake and reinforces warming. Scientists increasingly warn that this is not just a gradual slowdown, but a potential regime shift in how surface and deep waters interact, with feedbacks that accelerate climate change.

Human and Ethical Stakes

For coastal and Indigenous communities, ocean circulation is not an abstract concept. It underpins food security, livelihoods, and cultural identity.

As researchers like Sarah Purkey warn that deep-ocean changes may unfold within a single lifetime, ethical questions intensify around responsibility, adaptation, and intergenerational fairness—especially for communities that contributed least to the emissions driving the change.

What the Science Signals Now

The discovery that only about four regions generate Earth’s deep ocean water—and that at least one is already failing—reveals how fragile this climate safeguard truly is. Scientists stress that rapid emissions cuts this decade could still slow the damage.

The fate of these remote Antarctic engines may ultimately shape future sea levels, marine ecosystems, and how effectively the ocean continues to breathe for the planet.

Sources:

Zhou, Shenjie, et al. “Slowdown of Antarctic Bottom Water export driven by climatic wind and sea-ice changes.” Nature Climate Change, vol. 13, June 2023, pp. 701-709.

Li, Qian, et al. “Abyssal ocean overturning slowdown and warming driven by Antarctic meltwater.” Nature, vol. 615, 29 March 2023, pp. 841-847.

Caesar, Levke, et al. “Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation.” Nature, vol. 556, 11 April 2018, pp. 191-196.

“Ice Shelf Collapse in East Antarctica.” NASA Earth Observatory, March 2022.