Life has been found thriving nearly 3.7 kilometers below the Greenland Sea, in what is now the deepest known gas hydrate cold seep on the planet. This ultra‑dark ecosystem feeds on methane and crude oil leaking from ancient organic material buried millions of years ago, showing that carbon locked away in Earth’s past can still power life in extreme places.

Researchers say sites like this are natural test labs that help answer urgent questions about how a warming ocean will interact with frozen methane reservoirs in coming decades.

Hidden oasis off Greenland

Far to the west of Greenland, along a deep undersea ridge called Molloy Ridge, scientists have mapped a previously unknown oasis on the otherwise bleak seafloor. These Freya gas hydrate mounds lie roughly 2.3 miles beneath the surface, at a depth that most tourist and commercial submersibles cannot safely reach.

The area sits in the Fram Strait, one of the planet’s key gateways where cold Arctic waters mix with the North Atlantic, making any new discovery there especially interesting for oceanographers.

Deepest methane seep yet

Freya is now recognized as the deepest gas hydrate cold seep ever documented, sitting about 11,940 feet below the ocean surface. Most gas hydrate seeps previously known to science occur at less than 2,000 meters, so this discovery pushes the depth limit for exposed hydrate outcrops by almost 1,800 meters.

Hydrates are ice‑like crystals where water molecules trap gas, mainly methane, under low temperatures and high pressures; they normally remain buried in sediments, not forming towering mounds on the seafloor.

A find that resets expectations

Giuliana Panieri, co‑chief scientist of the mission from UiT The Arctic University of Norway, described the discovery as one that “rewrites the playbook for Arctic deep‑sea ecosystems and carbon cycling.” Her team reports that the Freya mounds are both geologically active and biologically rich, forcing scientists to rethink how biodiversity and carbon flows are linked in the High North.

The site appears to connect two types of extreme environments once thought to be fairly separate: methane seeps and hydrothermal vents, with species and ecological roles overlapping between them.

Inside the Arctic Deep mission

The Freya mounds were discovered in May 2024 during the Ocean Census Arctic Deep – EXTREME24 expedition, a 22‑day voyage devoted to some of the harshest environments in the Arctic Ocean. Led by UiT in partnership with REV Ocean and other institutions, the mission brought together experts in geology, biology, and geochemistry aboard a single research vessel.

Their goal was to explore parts of the seafloor that had never been seen in detail, using advanced mapping tools and robotic vehicles to search for hidden habitats. The team focused on the Molloy Ridge because earlier surveys had hinted at unusual gas signals and steep seafloor topography there.

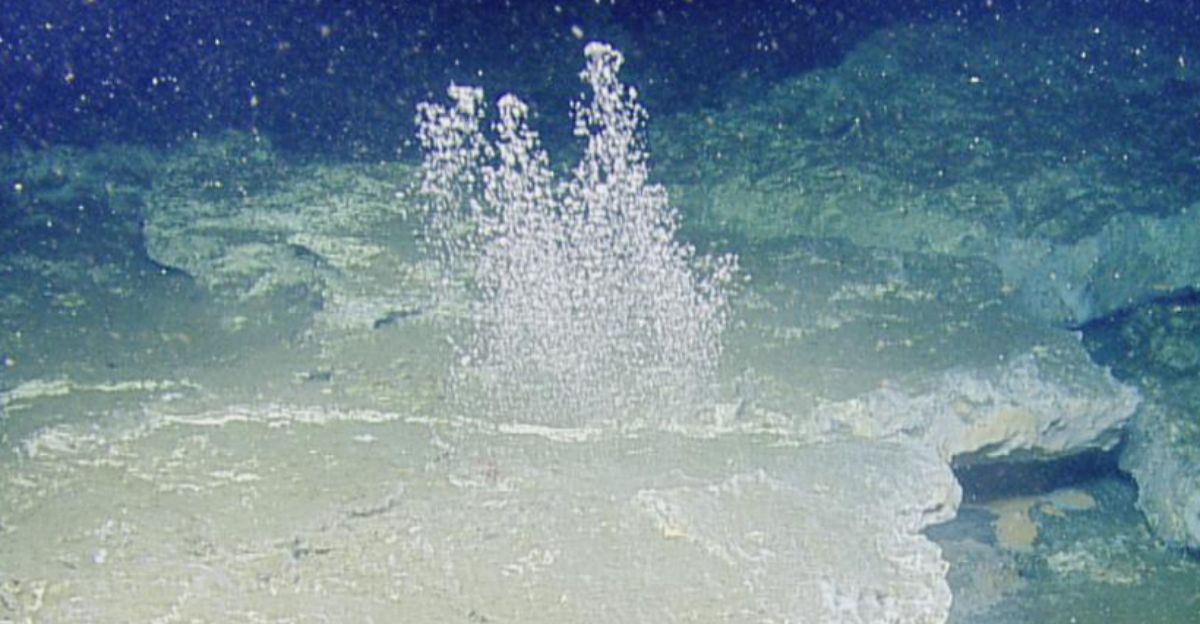

Chasing a towering gas flare

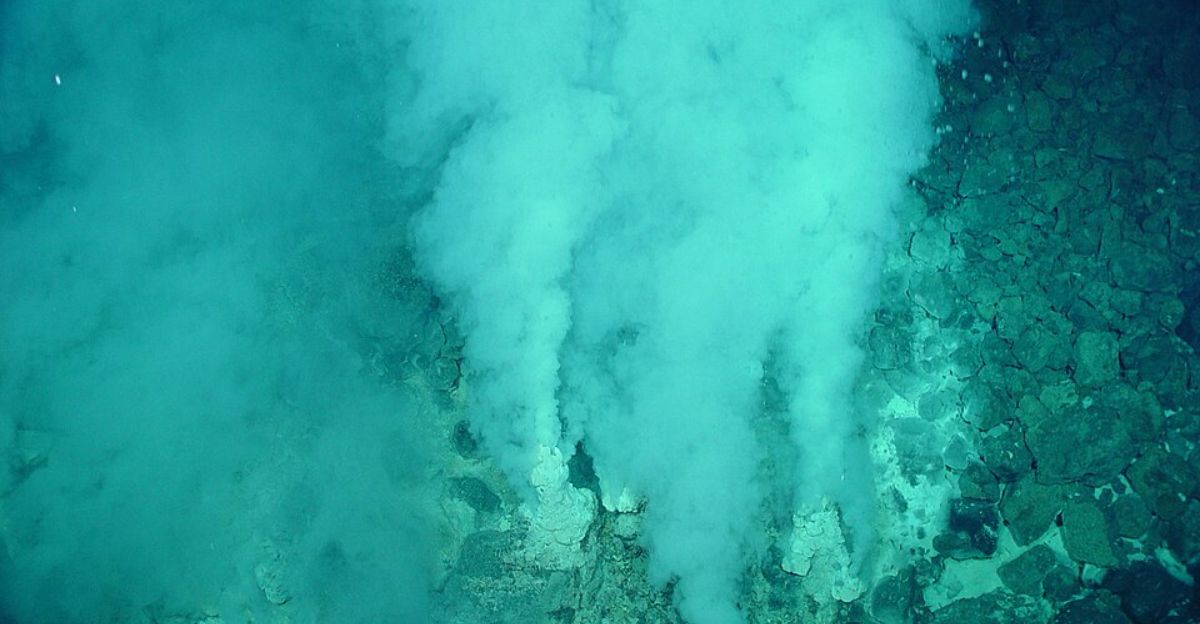

The breakthrough began when the ship’s multibeam echosounder picked up a striking column of bubbles shooting up through the water column above Molloy Ridge. The acoustic images showed a gas flare rising thousands of meters toward the surface, a strong sign that methane was escaping from the seafloor below.

Once they had narrowed down the source, the crew launched a deep‑diving remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to investigate what lay on the bottom.

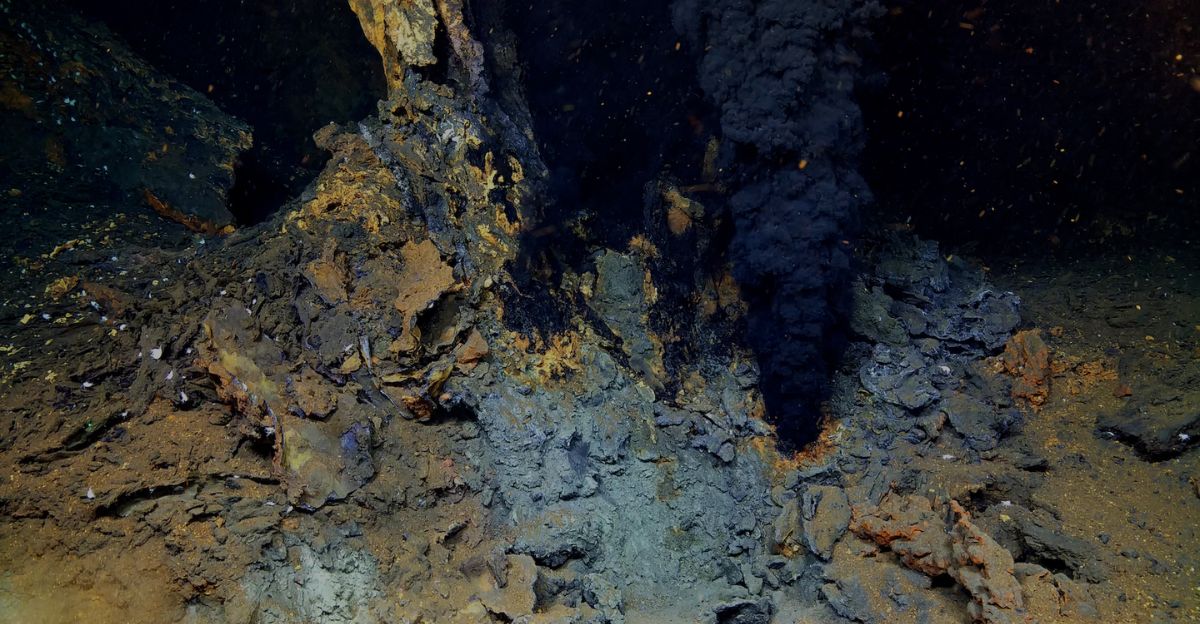

ROV Aurora’s dive into blackness

The ROV Aurora, operated by REV Ocean, then descended almost four kilometers through frigid, pitch‑black water to reach the seafloor. Guided from the ship by pilots watching live camera feeds, the vehicle used thrusters and sonar to navigate just a few meters above the rugged terrain.

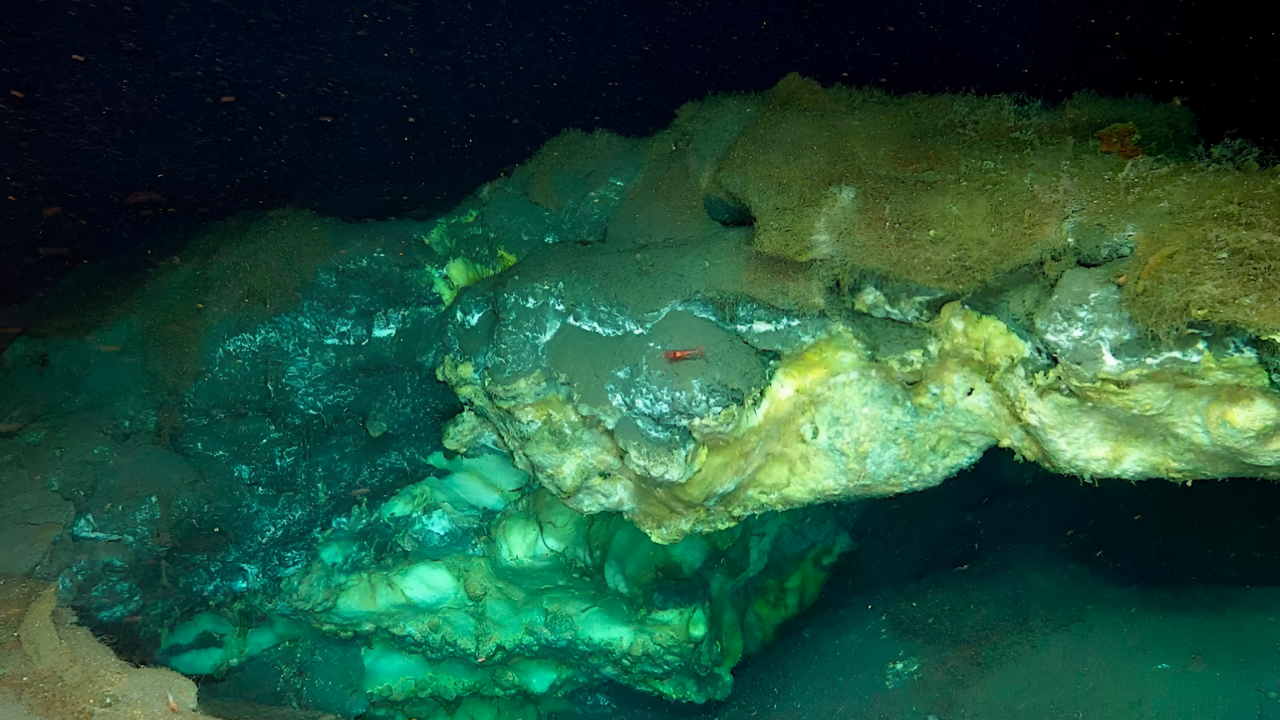

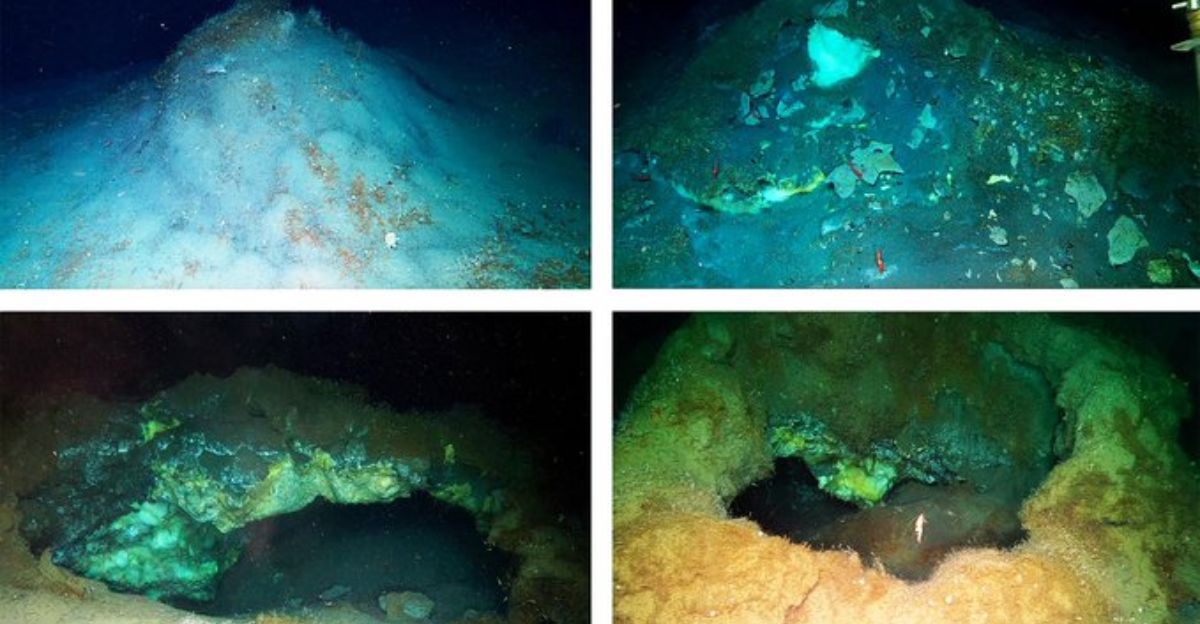

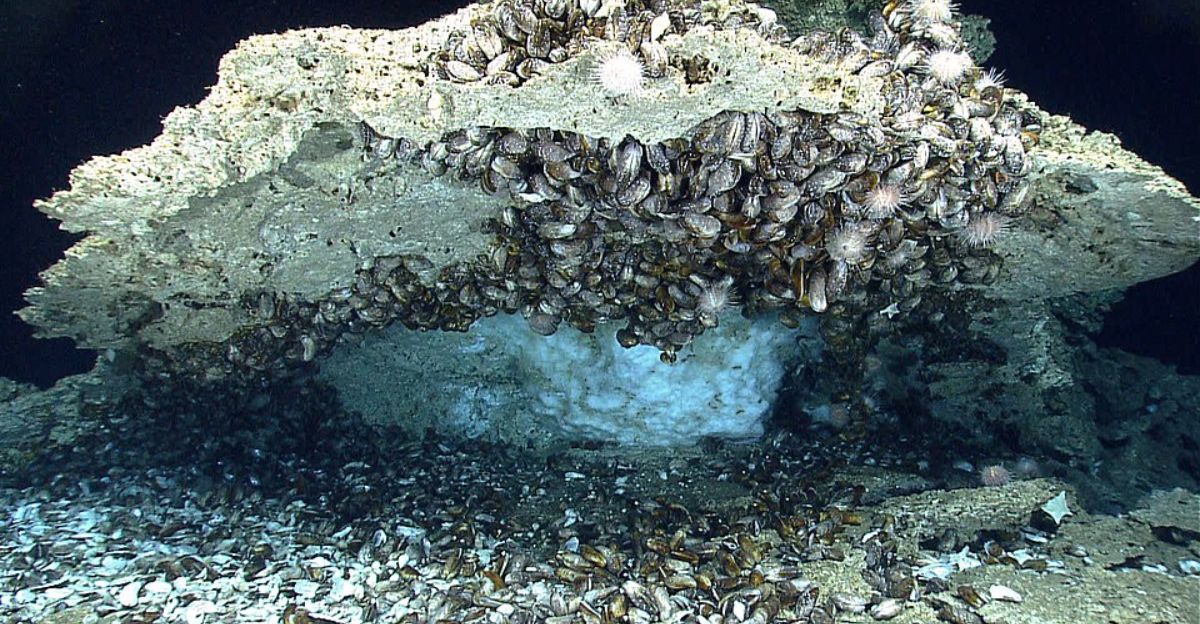

When Aurora’s lights finally swept across the bottom, they revealed ice‑like domes and mounds jutting up from the sediment, some coated with pale microbial mats and clusters of animals.

Naming the Freya mounds

The team named the newly revealed features the Freya gas hydrate mounds, after the Norse goddess linked to fertility, love, and life. The seafloor landscape includes cone‑shaped mounds several meters across, as well as narrow ridges and arch‑like forms where hydrate has been exposed and sculpted by fluids and currents.

Between these high points lie pit‑like depressions that appear to mark places where hydrate once existed but has since destabilized and collapsed.

Methane, oil and chemical energy

At Freya, methane gas and crude oil seep directly from the seafloor, trapped in and around the icy hydrate deposits before escaping into the water. Tiny chemosynthetic microbes use chemical reactions involving methane and sulfide to convert inorganic carbon into organic matter, effectively creating food from gas rather than sunlight.

These microbes form mats on rocks and hydrates or live inside the tissues of some animals, acting as internal power plants for their hosts. In turn, larger organisms graze on the microbes or prey on each other, building a full food web rooted in chemical energy.

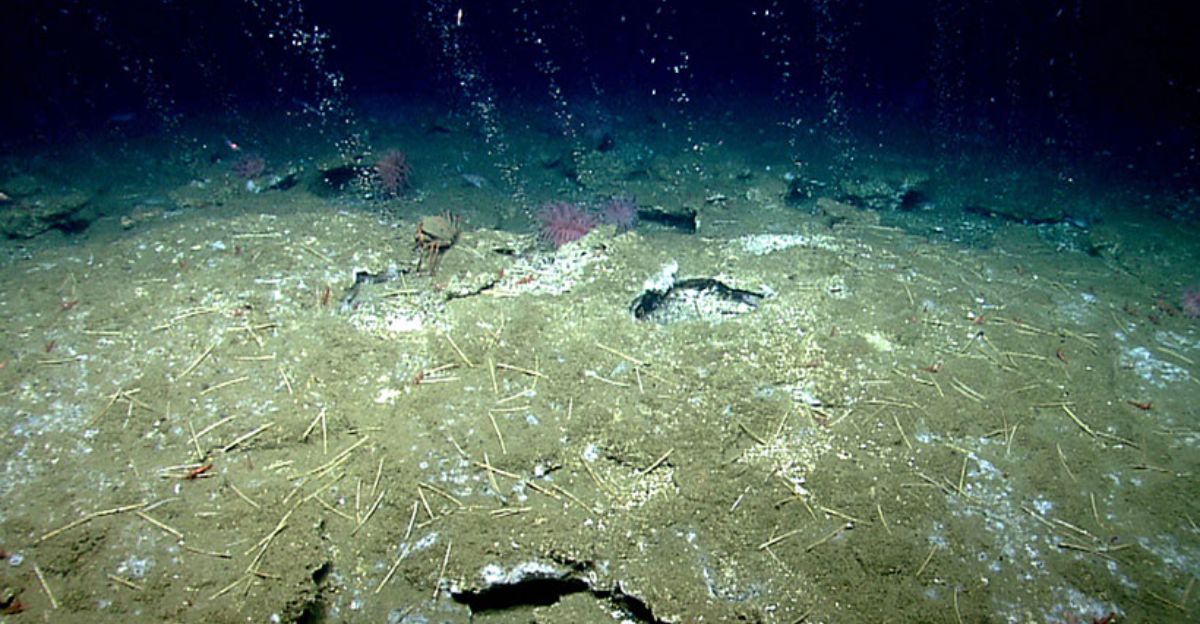

Specialist life in the dark

The Freya mounds are crowded with deep‑sea specialists, including siboglinid and maldanid tubeworms, tiny skeneid and rissoid snails, melitid amphipods, bristle worms, bivalves, and shrimp‑like crustaceans. Many of these animals live burrowed into the sediments or attached directly to the hydrate, where they can best access the microbial communities that fuel the ecosystem.

Some worms host symbiotic bacteria inside their bodies, trading shelter for nutrients, while others graze on bacterial mats or scavenge drifting particles of organic material.

Life with no sunlight at all

Unlike most marine ecosystems, which ultimately depend on sunlight and photosynthesis at the surface, Freya’s community is powered entirely by chemical reactions. No sunlight reaches 3,640 meters depth, so there are no plants or algae; instead, microbes use methane and other reduced compounds as fuel, a process called chemosynthesis.

This strategy proves that the deep Arctic seafloor is far from a biological desert and can support complex, multi‑layered food webs even at extreme depths and pressures. Similar chemosynthetic ecosystems have been found at hydrothermal vents and shallower seeps elsewhere, but Freya extends this model to colder, deeper, and more isolated terrain.

Ancient forests as fuel

Chemical fingerprints in the gas and oil at Freya show that they are thermogenic, meaning they were produced when buried organic matter was cooked under high heat and pressure deep within Earth’s crust. The source material dates back to the Miocene epoch, roughly 23 to 5.3 million years ago, when Greenland’s climate was significantly warmer and covered in flowering plants and forests.

Over millions of years, plant and plankton remains sank into sedimentary basins, where they were slowly transformed into hydrocarbons. Faults and fractures in the rock then provided pathways for these gases and oils to migrate upward toward the seafloor, where they became trapped in gas hydrates.

Greenland’s warm past under ice

Because of this history, the Freya mounds connect the modern frozen Arctic to a time when Greenland looked more like a temperate or even subtropical landscape. During the Miocene, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations were higher than today, global temperatures were warmer, and sea levels stood tens of meters above current levels.

Now, as methane and oil derived from that material seep out nearly four kilometers below the waves, they sustain animals that never see daylight and live in water barely above freezing.

A restless seafloor of ice and gas

Researchers have mapped a full sequence of hydrate features at Freya, from smooth sedimented domes to exposed mounds and arches, and finally to collapsed pits, showing that the system is constantly changing. Gas hydrate deposits are considered metastable, which means that small shifts in temperature, pressure, or fluid flow can cause them to grow, crack, or suddenly break down.

At Freya, that instability appears to sculpt the landscape over time, as new hydrate forms and old structures fail, leaving behind sinkhole‑like depressions. These changes can redirect pathways for gas and fluids, in turn altering where chemosynthetic communities can thrive.

A vast but delicate methane store

Globally, scientists estimate that roughly 20 percent of Earth’s methane is locked in gas hydrate form within deep marine sediments, representing billions of tons of carbon. That storehouse dwarfs the methane currently in the atmosphere, making hydrates a crucial piece of the climate puzzle if they begin to destabilize on large scales.

Ultra‑deep systems like Freya serve as natural laboratories for studying how methane behaves as it escapes from sediments and moves through the ocean under different conditions. At the same time, researchers caution that most methane released from deep sites never reaches the air, because it dissolves in water or is consumed by microbes on its way up.

Bubble plumes and carbon cycling

At Freya, methane flares rise more than 3,300 meters through the water column, ranking among the tallest bubble plumes ever documented. As the bubbles ascend, changing pressure and temperature strip away their hydrate coatings, and much of the methane dissolves into the surrounding seawater.

Once dissolved, the gas can be oxidized by microbes, turning methane into carbon dioxide and helping regulate how much reaches higher waters or the atmosphere. Data from sensors and water samples collected in and around the plume are now being fed into climate and ocean circulation models to refine predictions.

A second surprise under Greenland’s ice

In a separate but related study, scientists used seismic data from 373 monitoring stations to map what lies beneath Greenland’s vast ice sheet. Instead of resting mostly on hard bedrock, large portions of the ice base were found to sit atop soft, water‑rich sediments that behave more like wet sand.

To make this discovery, researchers analyzed how seismic waves from distant earthquakes changed speed and direction as they passed under the ice, revealing whether they were travelling through rock, ice, or sediment.

Sea‑level rise pressures grow

Because Greenland is already one of the largest contributors to global sea‑level rise, the discovery of soft sediments beneath its ice suggests that meltwater may reach the ocean faster than many models currently assume. Ice can slide more easily over wet, deformable sediment than over solid rock, potentially speeding the flow of glaciers toward the coast as surface melting increases.

If that happens, oceans could rise sooner and higher than some existing projections, putting extra pressure on coastal cities and low‑lying nations to adapt. The new subglacial map will help ice‑sheet modelers update their simulations to better capture this slippery base.

Mining, methane and fragile oases

The Freya discovery comes at a moment when interest in deep‑sea mining and Arctic resource extraction is rapidly growing, raising questions about how to protect fragile seafloor ecosystems. The Freya mounds lie in a region Norway opened for seabed mineral exploration in early 2024, though authorities have since paused mining in some deep areas until 2029 amid public concern.

Scientists argue that sites like Freya, which host unique biodiversity and act as natural laboratories for climate‑relevant processes, should be off‑limits to industrial disturbance.

Rethinking the Arctic’s future

Together, the discovery of a thriving ultra‑deep, methane‑fueled ecosystem and the realization that Greenland’s ice rides over slippery sediments challenge long‑held ideas about a simple, frozen Arctic. Instead, both the seafloor and the ice sheet base emerge as active players in how carbon and water move through the Earth system.

Policymakers now face the task of integrating this new science into decisions about conservation, energy, and long‑term planning for life along the world’s coasts

Sources:

UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Deepest gas hydrate cold seep ever discovered in the Arctic, 2025-12-21

ScienceAlert, World’s Deepest Gas Hydrate Discovered Teeming With Life Off Greenland, 2025-12-28

Newsweek, Deep-sea oasis discovered 2.5 miles below Arctic stuns scientists, 2026-01-07

Phys.org, Widespread sediments beneath Greenland make its ice more mobile, 2025-12-11

Yahoo News, Scientists issue warning after making surprising discovery under Greenland’s ice sheet, 2025-12-29