In the arid terrain near Guadalajara, Spain, paleontologists have uncovered four titanosaur eggs so impeccably preserved that their microscopic structures remain intact after 72 million years. The discovery at the Creta in Poyos excavation site represents one of Europe’s most significant dinosaur finds in decades, challenging long-held assumptions about these massive herbivores’ presence on the continent during the Cretaceous period’s final chapter.

Francisco Ortega and Fernando Sanguino from UNED led the research team with regional government backing, relocating the specimens to the Palæontological Museum of Castilla-La Mancha in Cuenca, where they now anchor a permanent exhibition. In November 2025, Deputy Minister of Culture and Sport Carmen Teresa Olmedo formally announced the find, describing it as possessing “worldwide significance” and being “extremely exceptional.”

A Paleontological Sweet Spot

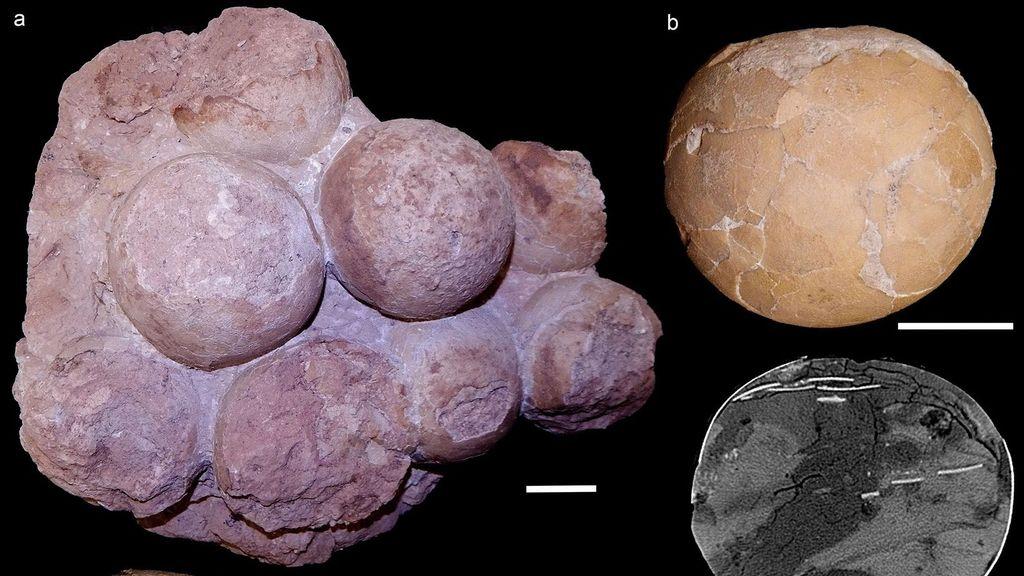

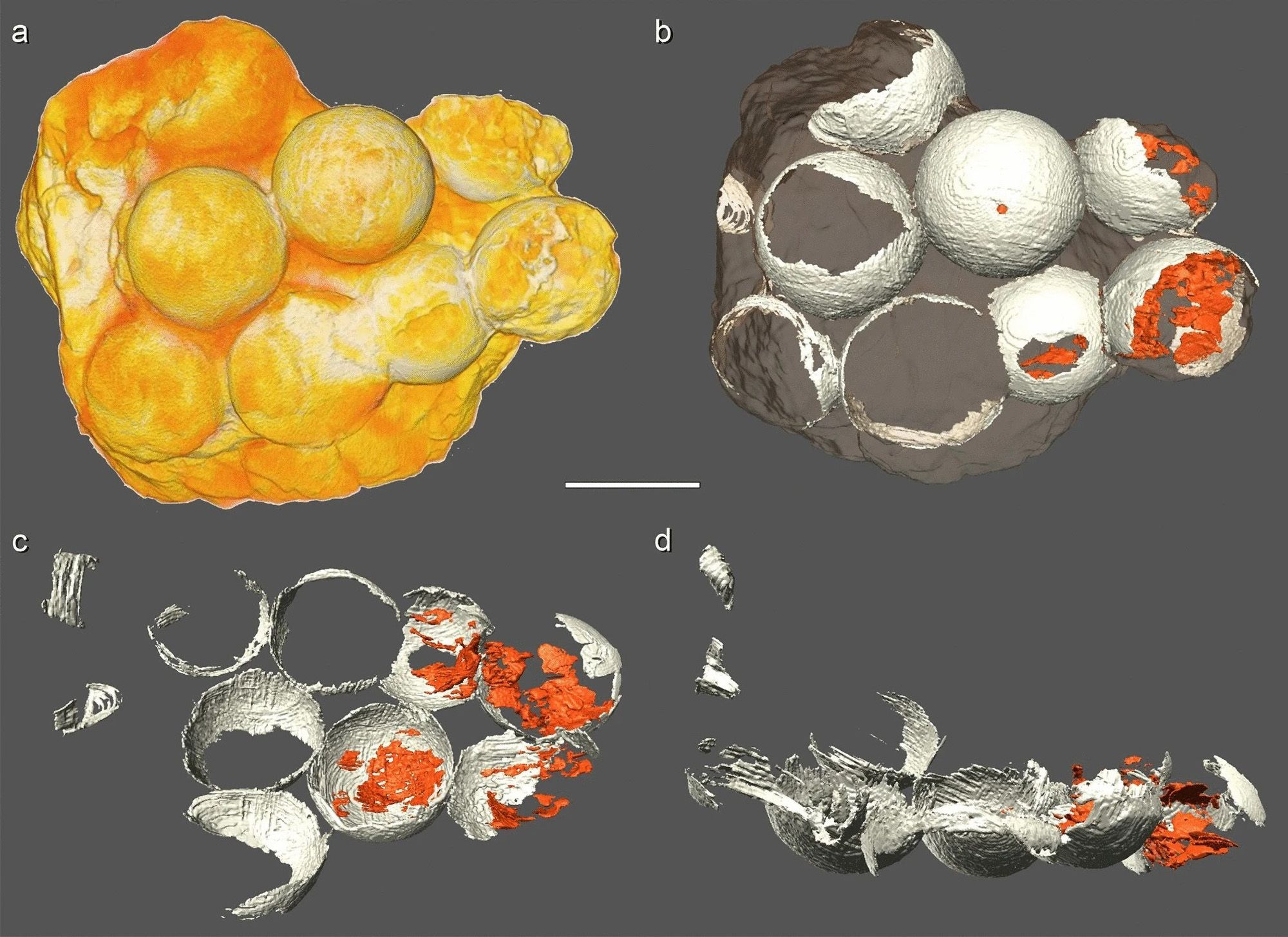

Unlike most dinosaur eggs that fossilize into fragmented shells or flattened impressions, these four specimens retained their original three-dimensional forms along with delicate internal features. Microscopic analysis revealed intact spheroids, porous channels, and complete shell architecture—details typically erased by geological pressure and time.

The exceptional preservation resulted from what researchers term ideal fossilization conditions: rapid burial beneath fine sediment during seasonal floods, minimal geological disturbance over millions of years, and chemical environments that stabilized organic structures rather than dissolving them. The Upper Cretaceous sediment layers at Poyos created a preservation environment so favorable that fragile egg components survived processes that ordinarily obliterate such delicate remains within centuries.

These microstructures provide unprecedented data about oxygen exchange during embryonic development, water regulation through shell walls, and mineral composition—information that skeletal fossils cannot supply. The pore channels demonstrate that titanosaur eggs required atmospheric gas exchange similar to modern reptilian and avian reproduction.

Two Species, One Mystery

The excavation yielded an unexpected puzzle: two distinct titanosaur egg types within the same sediment layer, a phenomenon rarely documented in paleontological records. Researchers identified the larger specimens as belonging to a newly classified species, Litosoolithus poyosi, while the second type matched Fusioolithus baghensis, previously known only from younger geological deposits elsewhere.

Litosoolithus poyosi defies conventional evolutionary patterns. Despite producing enormous eggs, this species developed unusually thin shells—a combination that contradicts the typical correlation between egg size and shell thickness. Larger eggs normally require thicker protective barriers to prevent structural collapse and moisture loss, yet these specimens challenge that rule.

The simultaneous presence of two titanosaur lineages raises compelling questions about Late Cretaceous ecology. Did separate species share nesting territories during the same breeding seasons, suggesting social tolerance or mutual habitat preferences? Alternatively, did geological processes mix remains from different time periods, creating an illusion of coexistence? Each interpretation carries distinct implications for understanding dinosaur behavior and ancient environmental dynamics.

Rewriting European Dinosaur History

For generations, paleontologists regarded European titanosaurs as marginal populations overshadowed by the continent’s smaller theropods, armored ankylosaurs, and duck-billed hadrosaurs. The Poyos discovery dismantles this narrative, establishing that titanosaurs maintained robust, reproducing populations throughout the Iberian Peninsula during the Late Cretaceous.

The existence of active nesting sites containing multiple species demonstrates successful adaptation to European ecosystems rather than temporary visits by stray individuals. This paradigm shift mirrors patterns across paleontological history: apparent rarity often reflects incomplete fossil sampling and preservation bias rather than actual biological scarcity.

Spain’s emergence as a premier location for Cretaceous research builds on discoveries at Lo Hueco, Morella, and the Ebro Basin, each contributing evidence of diverse dinosaur communities. The Poyos eggs solidify the Iberian Peninsula’s status as a critical region for understanding Late Cretaceous biodiversity and reproductive ecology.

Racing Against Geological Time

The specimens date precisely to 72 million years ago—a mere six million years before the asteroid impact that terminated non-avian dinosaur lineages. This timing positions the eggs within Earth’s final dinosaur era, documenting populations that thrived during the Cretaceous period’s closing chapter. The healthy clutches suggest ecological stability and successful reproduction rather than populations already in decline.

Researchers now confront urgent questions about undiscovered sites across Europe’s exposed Cretaceous deposits. Climate change, urban development, and natural erosion continuously destroy fossil-bearing formations before systematic surveys can document them. The Poyos success demonstrates that transformative discoveries remain achievable across thousands of square kilometers of largely unexplored sedimentary layers.

Current research priorities include isotopic analysis to reconstruct ancient temperatures, rainfall patterns, and maternal diet, alongside phylogenetic studies comparing these specimens with titanosaur eggs from Argentina, India, and China. Museums throughout Spain are reexamining collections with fresh perspectives, potentially identifying additional Litosoolithus poyosi examples previously misclassified.

These four eggs ultimately illuminate how fragmentary fossil records consistently underestimate ancient biodiversity. They establish that European titanosaurs not only existed but flourished, reproduced successfully, and maintained species diversity in environments once thought inhospitable to these 50-ton giants. As geological records yield their secrets through careful excavation, the boundaries of scientific understanding continue expanding, revealing ecosystems far richer than skeletal remains alone could document.

Sources:

Sanguino et al. 2025, Cretaceous Research journal; UNED paleontology research team documentation

Museo de Paleontología de Castilla-La Mancha (MUPA) November 2025 exhibition announcement; Junta de Castilla-La Mancha cultural heritage department

Viceconsejería de Cultura y Deportes official statement November 2025 (Carmen Teresa Olmedo)

Villalba de la Sierra Formation geological surveys; Spanish Cretaceous paleontological database