A volcano in northeastern Africa stayed quiet for 12,000 years. Scientists didn’t think it would erupt.

Then, in November 2025, seismic sensors detected magma moving deep below the surface. Monitoring agencies across three continents tracked invisible ash and gas clouds as they spread across borders.

Hundreds of millions of people faced an air quality crisis they never expected. What could wake up a volcano after 12 millennia?

Magma Migration

Six months before the main eruption, scientists spotted trouble 25 miles away. Erta Ale volcano erupted violently in July 2025—unusual for an already-active system.

COMET researchers warned that magma was moving through underground channels beneath the East African Rift. This rift is where tectonic plates split apart, creating connected volcano chambers.

By fall, pressure continued to build underneath. Nobody knew which volcano would blow first.

The Silent Zone

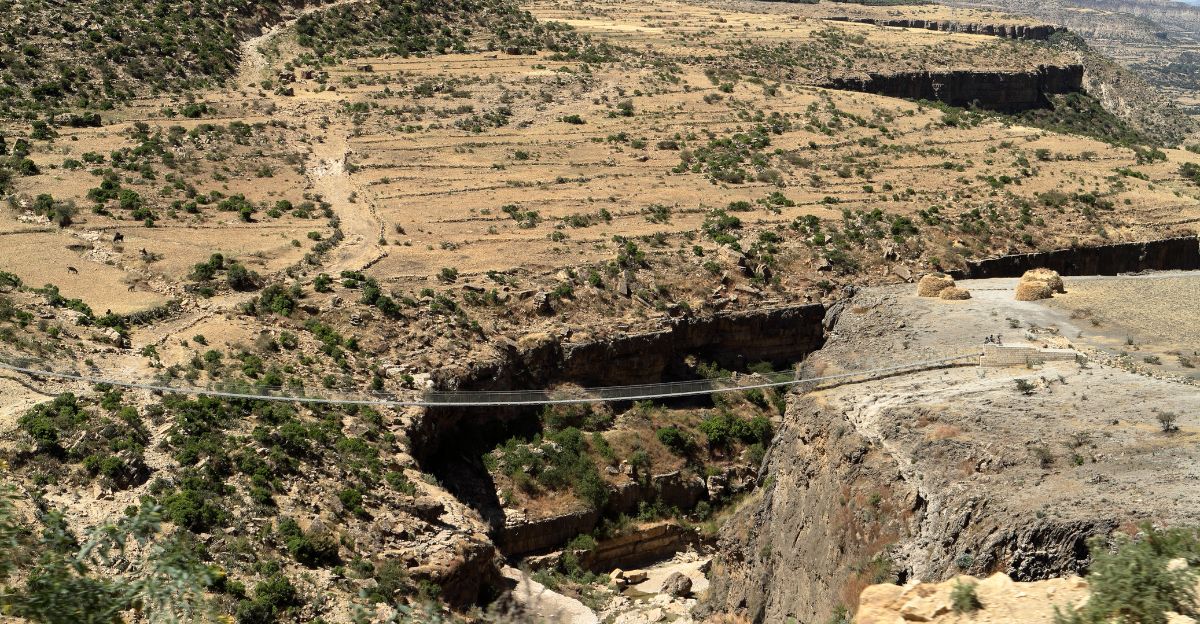

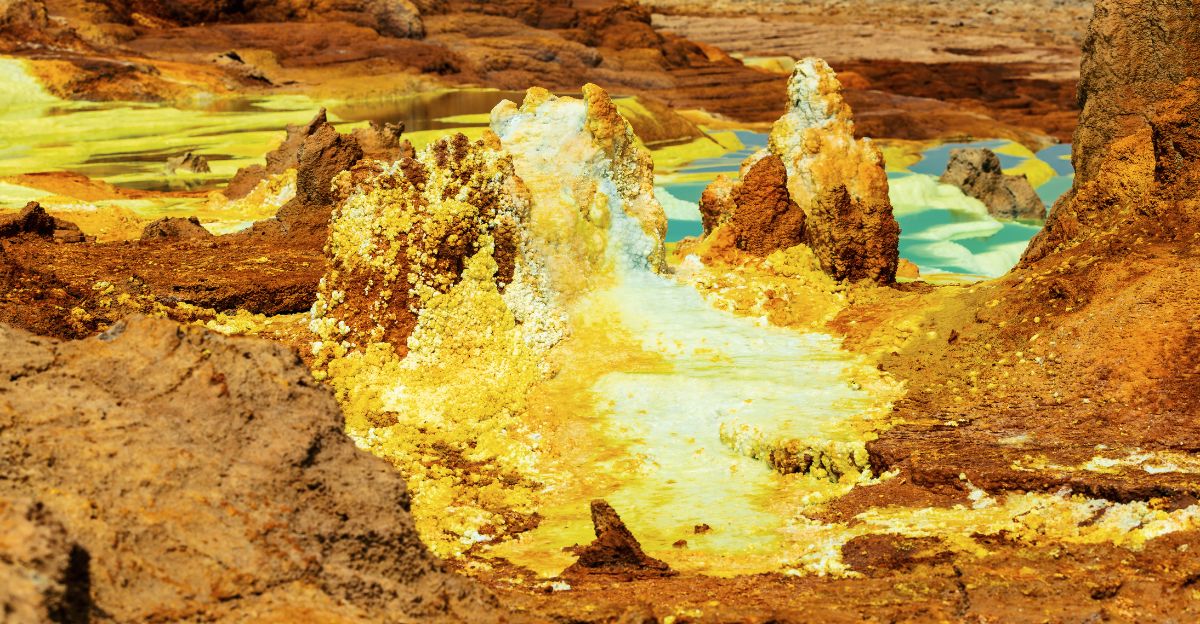

Hayli Gubbi sits in Earth’s most remote volcanic areas: the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia’s Afar region. Three tectonic plates converge here, but few people reside there, except for herders and researchers.

The volcano rises 4,140 feet and has had no known eruptions in recorded history, with 12,000 years of inactivity. Few earthquake sensors monitored it closely. No evacuation plans existed.

When geological chaos struck, warning systems were barely in place. What happens when a volcano wakes up unsupervised?

The Pressure Mounts

By mid-November 2025, earthquake tremors beneath Hayli Gubbi grew stronger. Ground instruments showed inflation—magma pushing upward through rock, swelling the volcano’s sides.

Regional seismic networks, short on funding, rushed to share information across borders. Aviation authorities received early warnings from volcanic ash centers. The Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre prepared alert bulletins.

Ethiopia’s disaster agency issued quiet warnings. But public announcements stayed silent. Nobody knew when the volcano might break open.

The Sudden Bomb

On November 23, 2025, at 8:30 UTC, Hayli Gubbi erupted with violent force. Ash and gas shot upward 33,000 to 49,000 feet in under one hour.

The eruption released about 220,000 tons of sulfur dioxide, a toxic gas that damages lungs and causes acid rain.

A nearby resident said the blast felt “like a sudden bomb had been thrown with smoke and ash.” Agencies got only minutes of warning. Ash crossed the Red Sea within hours.

Yemen’s Gray Sky

By November 24, ash from Hayli Gubbi crossed the Red Sea and reached Yemen’s coast. The volcanic plume dropped particles on cities near Sana’a and Hodeidah.

Air quality monitors indicated hazardous levels of sulfur dioxide and fine particulate matter. Yemen’s health ministry has advised residents, particularly children, the elderly, and those with respiratory problems, to stay indoors.

Hospital emergency rooms experienced a surge in respiratory complaints within 24 hours. The country lacked sufficient healthcare resources to handle the crisis at this distant volcano.

Oman’s Choking Crossroads

Oman, located downwind along the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, experienced heavier ashfall. The volcanic plume settled across port cities and highlands, turning skies gray.

Visibility dropped dangerously. Oman’s environment authority issued a health advisory, recommending N95 masks for outdoor workers. Fishermen reported that ash was coating their boats and contaminating their catch. Livestock refused to eat ash-covered grass.

One local report described it as “sudden and unprecedented”—a description that matches the account of the Ethiopian resident. Port cranes stopped working due to poor visibility.

Aviation’s Nightmare

Within 36 hours, aviation authorities across the Middle East and South Asia issued emergency warnings. Volcanic ash damages jet engines, causing them to malfunction and cease operation at cruise altitude.

The Toulouse Ash Advisory Centre urged all aircraft to avoid the airspace of the Arabian Peninsula and India. Airlines, including Air India, Emirates, and Pakistan International, cancelled or rerouted flights.

Major airports in Delhi, Dubai, and Islamabad saw big delays. One analyst estimated carriers lost $50 million daily.

India’s Respiratory Crisis

By November 24, the volcanic plume reached India. Cities in the north—including Delhi, already choked by winter smog—hit hazardous air quality levels. Volcanic ash mixed with existing pollution created dangerous breathing conditions.

Delhi’s aviation authority issued a visibility warning mentioning volcanic ash. Hospitals reported a 30-40% increase in respiratory complaints, asthma attacks, and allergies over a two-day period.

Construction sites and schools shut down. India’s environment ministry confirmed sulfur dioxide exceeded safe limits in many cities.

The Forgotten Rift’s Warning

As scientists studied satellite photos and gas measurements, a bigger pattern emerged. The East African Rift—stretching 3,975 miles from Lebanon to Mozambique—is deforming at an accelerated rate.

Magma chambers under multiple rift volcanoes are building pressure simultaneously. Hayli Gubbi’s eruption wasn’t unique; it signaled something larger.

COMET and Edinburgh University researchers warned that dormant volcanoes across the rift—in Kenya, Tanzania, and the Congo—face an increased risk of eruption soon. This event revealed that the rift’s volcanic system was more active than scientists had previously thought.

Pakistan’s Silent Sufferers

Pakistan’s northern regions, including Islamabad and Lahore, experienced ashfall on November 24 and 25. The ash plume initially reached southern Pakistan, accompanied by reports of reduced visibility and worsening air quality.

Pakistan was unable to monitor and warn about volcanic ash like India could. A few weather stations detected the plume, but public warnings came too late.

Health workers heard residents complaining about breathing problems, unaware that ash—not regular smog—was the cause. One Pakistani scientist expressed frustration about the lack of warning.

China’s Eastern Margin

By November 25-26, satellite images showed the volcanic plume had traveled over 2,000 miles and reached China’s western regions. Air quality monitors in Xinjiang and Tibet recorded raised sulfur dioxide and dust levels.

The ash concentration was lower than in Arabian regions or India, weakened after traveling such a distance, but still measurable and concerning. China’s environment ministry confirmed the presence of volcanic ash in air quality reports.

The eruption’s reach to China’s far west proved that one volcano can affect four or five nations across half the world.

The Volcanic Drought Aftermath

By November 25, the main eruption stopped, but damage continued. Ashfall covered livestock pasture in Ethiopia’s Afar region for nomadic herding communities.

Water sources collected ash, becoming unsuitable for drinking without treatment. Livestock exhibited stress from consuming vegetation contaminated with ash. International aid groups reported that more herders are seeking emergency fodder assistance.

Veterinary experts warned that ash contamination posed health risks to herds through ingestion. The crisis became ecological and economic for vulnerable populations, the least able to prepare.

The Monitoring Gap Exposed

After the eruption, scientists and officials found major weaknesses. Ethiopia’s earthquake network had few stations near Hayli Gubbi, with slow data transmission. Coordination between African, Middle Eastern, and South Asian weather services was informal and weak.

Early warning systems were expected to detect eruptions from well-known, monitored volcanoes—not 12,000-year-old dormant ones. The crisis sparked emergency meetings at the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and the Global Volcanism Program.

A German expert stated that “Hayli Gubbi proved we’re still flying blind on half the world’s volcanoes.”

Will the Rift System Awaken?

Scientists monitoring the East African Rift face one critical question: Was Hayli Gubbi’s November 2025 eruption a one-time event, or the first sign of a larger awakening?

Magma chambers beneath dormant volcanoes in Kenya, Tanzania, the Congo, and beyond are showing rising pressure. The rift’s spreading rate suggests tectonic stress is building.

If this continues, another large eruption in the next 5-10 years is geologically possible. The Hayli Gubbi eruption reminded us that geological change operates on massive time scales.

Sources:

- Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, Report on Hayli Gubbi (Ethiopia), November 2025

- COMET (University of Bristol), Hayli Gubbi Eruption Analysis, November 2025

- NASA Earth Observatory, Hayli Gubbi’s Explosive First Impression, December 2025

- Nature Geoscience, East African Rift Volcanic Activity Study, December 2025

- Scientific American, Hayli Gubbi Volcano Erupts in Ethiopia for First Time in More Than 12,000 Years, November 2025

- CNN, Ethiopia’s Hayli Gubbi volcano erupted for the first time in nearly 12,000 years, November 2025