Hidden beneath the French countryside for more than 57,000 years, a remarkable cave has revealed something extraordinary: the oldest known Neanderthal engravings ever discovered. These weren’t created by modern humans, but by our long-vanished cousins, challenging everything we thought we knew about who could create art and what it means to be human.

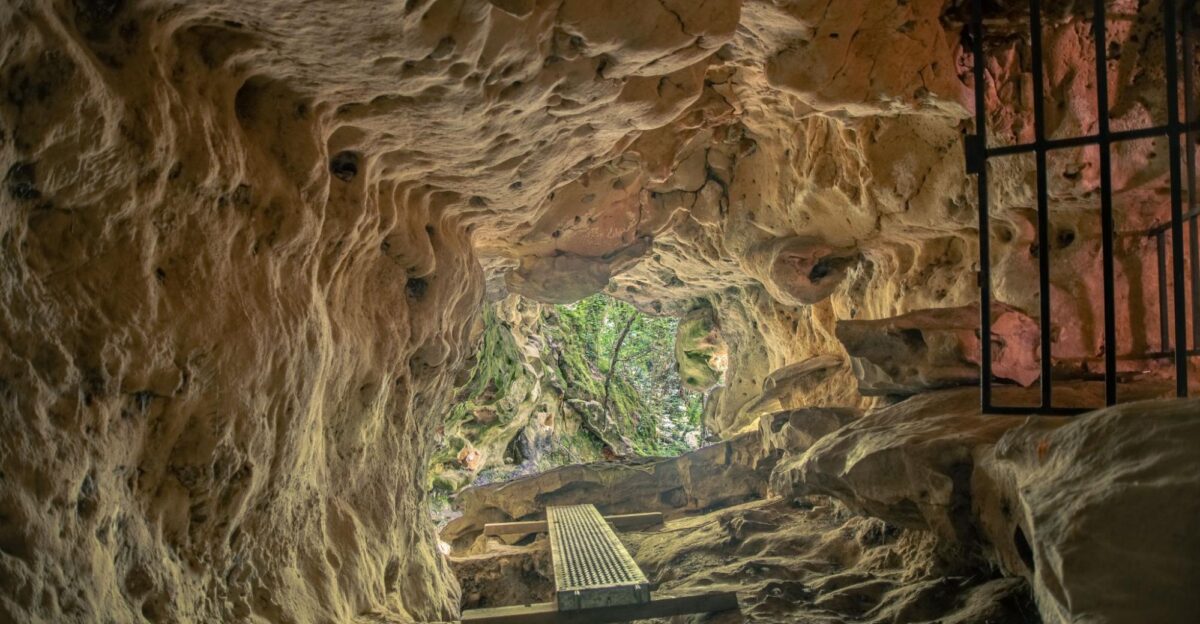

La Roche-Cotard cave, tucked into a hillside above France’s Loire River, contains mysterious patterns traced by Neanderthal fingers into soft rock. Researchers discovered lines, dots, and carefully organized panels that prove our ancient relatives had the ability to think symbolically and express themselves creatively.

A Hidden Cave Above the Loire River

The La Roche-Cotard cave system sits high above the Loire River in central France’s scenic Loire Valley, a region famous today for vineyards, châteaux, and wine tourism rather than prehistoric secrets. This modest limestone cave provided shelter for Neanderthals who hunted large animals, butchered their prey, and created something remarkable.

Tuffeau is a fine-grained, creamy-white limestone formed about 90 million years ago from marine sediments, ancient mollusk shells, and sand particles. The same stone that Neanderthals drew upon would later be used to build the Loire Valley’s famous Renaissance châteaux.

Sealed for 57,000 Years

Sometime between 57,000 and 75,000 years ago, the Loire River repeatedly flooded the cave entrance. River sediments mixed with hillside erosion gradually buried the opening under more than 30 feet of deposits, effectively sealing everything inside like a prehistoric time capsule.

No later visitors could enter. No weather could erode the markings. The sealed cave became a frozen moment in time, protecting evidence of Neanderthal life and creativity for millennia. Scientists used a sophisticated dating technique called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to determine when the cave entrance closed.

Accidentally Discovered in 1846

The cave’s modern story began during the Industrial Revolution. In 1846, workers building a railway line through the Loire Valley cut into the hillside and accidentally broke through the ancient seal, exposing the long-hidden cave entrance. At that time, nobody understood what they had found. The concept of prehistoric archaeology barely existed, and Neanderthals wouldn’t be properly identified as a distinct human species for another decade.

The first proper archaeological excavation came in 1912, when site owner François d’Achon dug through the cave’s interior sediments. He retrieved Mousterian stone tools, sophisticated flake implements uniquely associated with Neanderthals in western Europe, along with animal remains. But the strange markings on the walls remained largely unexplained and overlooked for decades.

Why These Aren’t “Human” Marks

The statement that these engravings were not made by humans relies on a crucial technical distinction: the artists were Neanderthals—Homo neanderthalensis—not Homo sapiens, our own species. While Neanderthals were certainly human in the broader sense, scientists often reserve the term “humans” specifically for anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

All artifacts recovered from the sealed layers of La Roche-Cotard belong to the Mousterian tool-making tradition, which in western Europe is uniquely and exclusively attributed to Neanderthals. These tools include distinctive scrapers, points, and flakes made using sophisticated techniques like the Levallois method.

Finger Drawings in Soft Stone

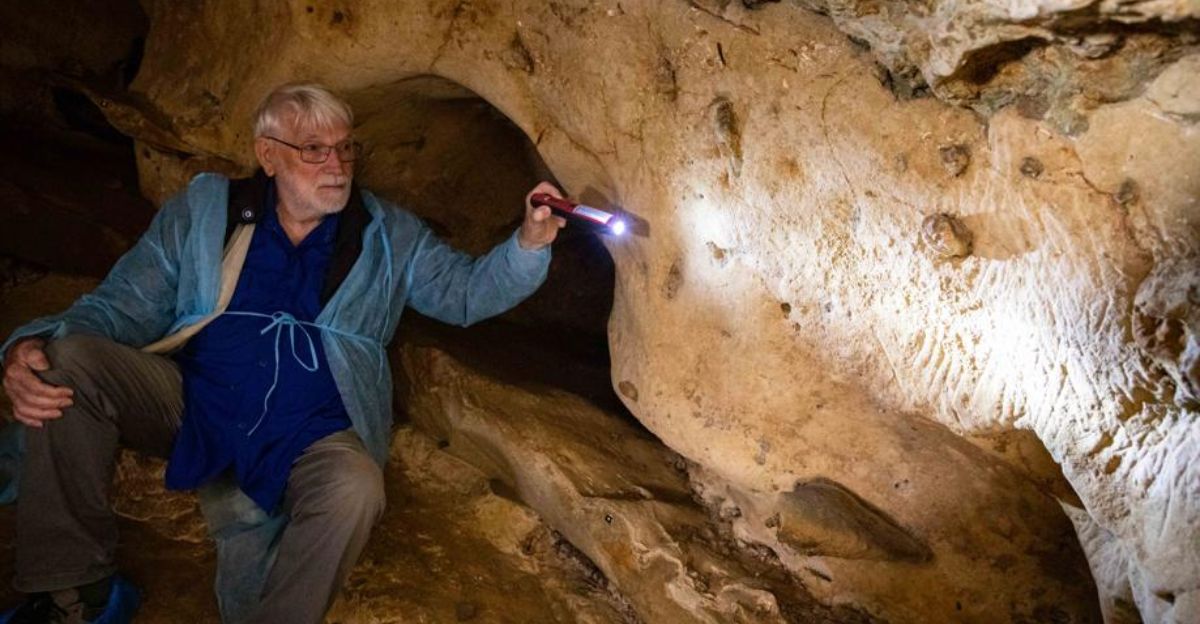

Inside a chamber called the Pillar Room, researchers documented remarkable panels of non-figurative engravings: parallel lines, sweeping arcs, grid patterns, and clusters of dots. These weren’t accidental marks, they were traced deliberately into the soft tuffeau using fingertips.

“When the tip of a finger comes into contact with this film, a trace is left in the shape of an impact; when the tip of the finger moves, an elongated digital trace is left”. The tuffeau’s surface has a permeable, sandy-clay film that responds perfectly to finger pressure. To confirm their interpretation, the research team visited a nearby cave made of the same tuffeau rock and conducted experiments.

Dating the Cave with Light

To establish when the cave entrance sealed shut, scientists employed optically stimulated luminescence dating, commonly called OSL. This radiometric technique has become essential for dating ancient cave deposits and archaeological sites. OSL works by measuring trapped electrons in mineral grains like quartz and feldspar. When sediments are exposed to sunlight, these electron traps empty completely, resetting the geological clock to zero.

In the laboratory, scientists expose sediment samples to intense light, releasing the trapped electrons which emit ultraviolet luminescence. The intensity of this glow reveals how long the minerals have been buried away from daylight. For La Roche-Cotard, researchers collected and analyzed 50 separate sediment samples from multiple locations inside the cave and from the deposits that once covered the entrance.

Closed Before Modern Humans Arrived

The luminescence dating provided a crucial insight: the cave closure predates the arrival of Homo sapiens in this part of Europe by many thousands of years. Archaeological evidence indicates modern humans didn’t reach western France until approximately 40,000 years ago, meaning the cave entrance had been sealed for at least 17,000 years before they arrived.

This timeline is absolutely essential to the research team’s conclusions. As Eric Robert of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris noted, several independent lines of evidence converge to demonstrate that Neanderthals, not modern humans, created these engravings.

Evidence of Daily Neanderthal Life

Excavations at La Roche-Cotard revealed far more than engravings. The cave floor contained sophisticated stone tools characteristic of Mousterian technology, including Levallois flakes and bifaces, tools associated with Neanderthal hunting and food processing strategies. The Mousterian industry represented a significant advancement in toolmaking, originating over 300,000 years ago and refined primarily by Neanderthals.

Scattered among the tools, researchers found cut-marked bones of large mammals showing that Neanderthals butchered their prey inside the cave. Some bones showed evidence of charring, indicating they cooked their food here using controlled fire. This combination of everyday subsistence activities with apparent symbolic wall marking suggests a more complex Neanderthal culture than previously imagined.

From Mystery to Scientific Certainty

For decades after the cave’s rediscovery, the unusual wall markings remained an archaeological puzzle. When researchers first noticed the organized finger tracings in the 1970s, their origin remained uncertain and debated. Were they natural geological features? Animal scratches? Marks left by 19th-century railway workers or early 20th-century excavators? Without proper analysis, these questions remained unanswered.

Starting in 2008, and intensifying from 2016 onward, a dedicated multidisciplinary team led by Jean-Claude Marquet and Eric Robert began systematically documenting every marking in the cave. They used advanced photogrammetry to create detailed 3D models of the engraved panels, allowing them to analyze each groove and ridge with extraordinary precision.

Building a 3D Case for Neanderthal Creativity

The research team’s use of detailed 3D photogrammetry became central to proving the markings’ authenticity. By plotting each groove, scratch, and ridge on virtual surfaces, scientists could analyze patterns invisible to the naked eye.

Most importantly, these 3D patterns could be compared directly with experimental markings. The team created test engravings using human fingers on similar tuffeau rock, animal claws on stone surfaces, and natural erosion patterns. Each left distinctively different traces.

Published Research That Changed Prehistory

On June 21, 2023, the research team published their comprehensive findings in PLOS One, an open-access scientific journal, under the title “The earliest unambiguous Neanderthal engravings on cave walls: La Roche-Cotard, Loire Valley, France.”

The study represented years of collaborative work by archaeologists, dating specialists, taphonomists (scientists who study how remains decay and preserve), and cave geology experts.

Shattering Previous Records

Before La Roche-Cotard, the oldest widely accepted Neanderthal cave engravings were abstract cross-hatching patterns discovered at Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar. The French discovery pushed the record for Neanderthal abstract art back by roughly 18,000 years, nearly doubling the known timespan of Neanderthal artistic expression.

This dramatic extension suggests that Neanderthal symbolic behavior wasn’t a brief, late-appearing phenomenon but represented a deep, long-lasting artistic tradition spanning tens of thousands of years.

Earlier Than Famous Human Cave Art

The La Roche-Cotard engravings predate Europe’s most celebrated Homo sapiens cave art by tens of thousands of years. Chauvet Cave in France, with its magnificent paintings of lions, mammoths, and other animals, dates to approximately 30,000-32,000 years ago. Spain’s El Castillo Cave, containing hand stencils and red discs, was created around 30,000-40,800 years ago.

Even more remarkably, the French Neanderthal engravings roughly match the age of the world’s oldest known figurative painting: a wild pig discovered in Sulawesi, Indonesia, dated to at least 45,500 years ago and created by Homo sapiens.

Part of a Deeper History of Mark-Making

Though La Roche-Cotard now anchors the oldest known Neanderthal cave engravings, it fits within a broader, fragmentary record suggesting that creating non-utilitarian marks is an ancient impulse across multiple hominin species. The urge to deliberately mark surfaces appears to stretch back hundreds of thousands of years, long before either Neanderthals or modern humans existed.

Evidence includes remarkable zigzag patterns carved into a freshwater mussel shell from Java, Indonesia, attributed to Homo erectus and dated between 430,000 and 540,000 years ago.

Messages We’ll Never Understand

What did the La Roche-Cotard panels mean to their Neanderthal creators? The honest answer is that we’ll never know. As the researchers candidly stated, interpreting these designs is impossible because they were created by a vanished population for an audience that shared their world, and that world is lost to us.

The engravings appear organized into coherent panels with internal structure, suggesting they held some meaning or significance. But without any living Neanderthal to explain them, these marks stand as haunting messages written in a language humanity has lost.

Abstract Neanderthals, Figurative Humans: Different Creative Minds

The stark contrast between Neanderthal abstract engravings and later Homo sapiens figurative paintings, herds of horses, stalking lions, powerful mammoths, raises profound questions about cognition, culture, and what art really means.

But modern research increasingly rejects this simplistic view. The differences between Neanderthal and Homo sapiens art may reflect different aesthetic choices, cultural values, and symbolic needs among coexisting human species rather than a hierarchy of capability.

Rewriting the Neanderthal Story

For generations following their first scientific description in the 19th century, Neanderthals suffered from a brutish stereotype, portrayed as dim-witted, hunched cavemen incapable of abstract thought, focused exclusively on survival, and lacking the creativity and symbolic thinking that made Homo sapiens special.

Art Isn’t Ours Alone

The La Roche-Cotard engravings fundamentally challenge the long-cherished idea that art, and by extension symbolic thought, is uniquely or originally “human” in the Homo sapiens sense. For decades, creating art was held up as the defining characteristic that separated us from all other species, including our closest extinct relatives. This discovery dismantles that comfortable assumption.

If Neanderthals were systematically creating abstract designs 57,000 or more years ago, and possibly as early as 75,000 years ago, then the roots of symbolic behavior stretch across species boundaries.

An Unsettling Question

For at least 57 millennia, La Roche-Cotard lay sealed, its walls silently bearing witness to marks left by Neanderthal hands that would never again touch them.

The cave’s preservation was entirely accidental, the result of ancient river flooding and hillside erosion that happened to bury the entrance at just the right depth to protect it from erosion but not so deep that it could never be found.

Sources:

PLOS One – “The earliest unambiguous Neanderthal engravings on cave walls: La Roche-Cotard, Loire Valley, France” – June 21, 2023

Smithsonian Magazine – “Oldest Known Neanderthal Engravings Were Sealed in a Cave for 57,000 Years” – June 20, 2023

Natural History Museum, London – “Oldest known Neanderthal engravings unearthed in French cave” – June 21, 2023

EurekAlert! – “Neanderthal cave engravings are oldest known” – June 20, 2023

CNRS – “Neanderthals were artists too” – June 28, 2023