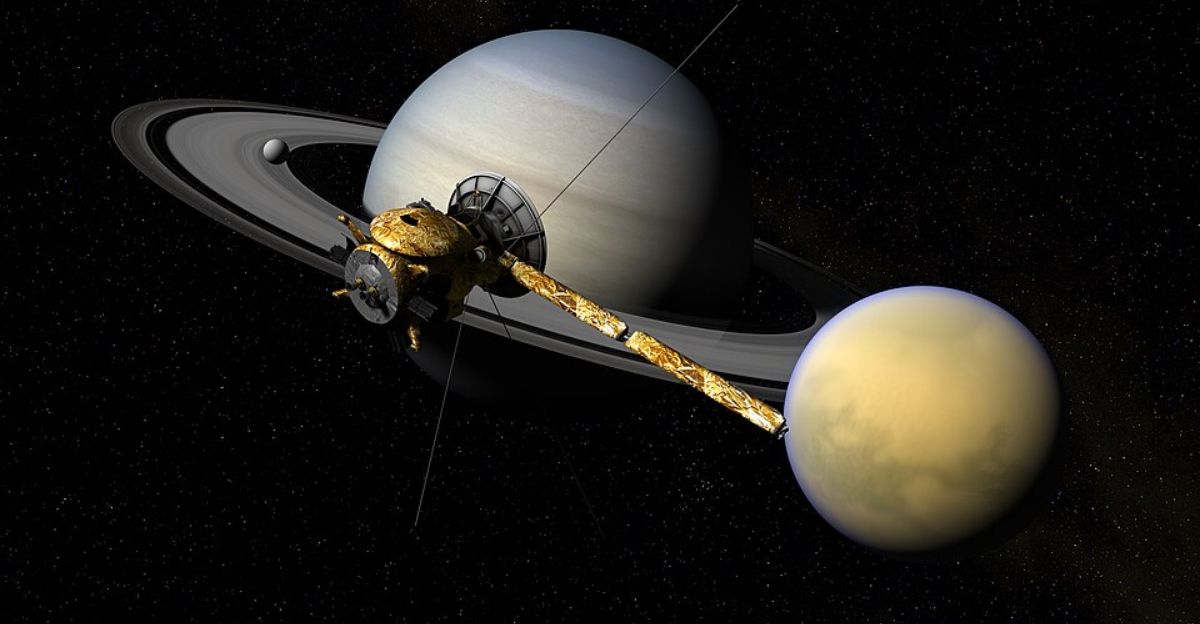

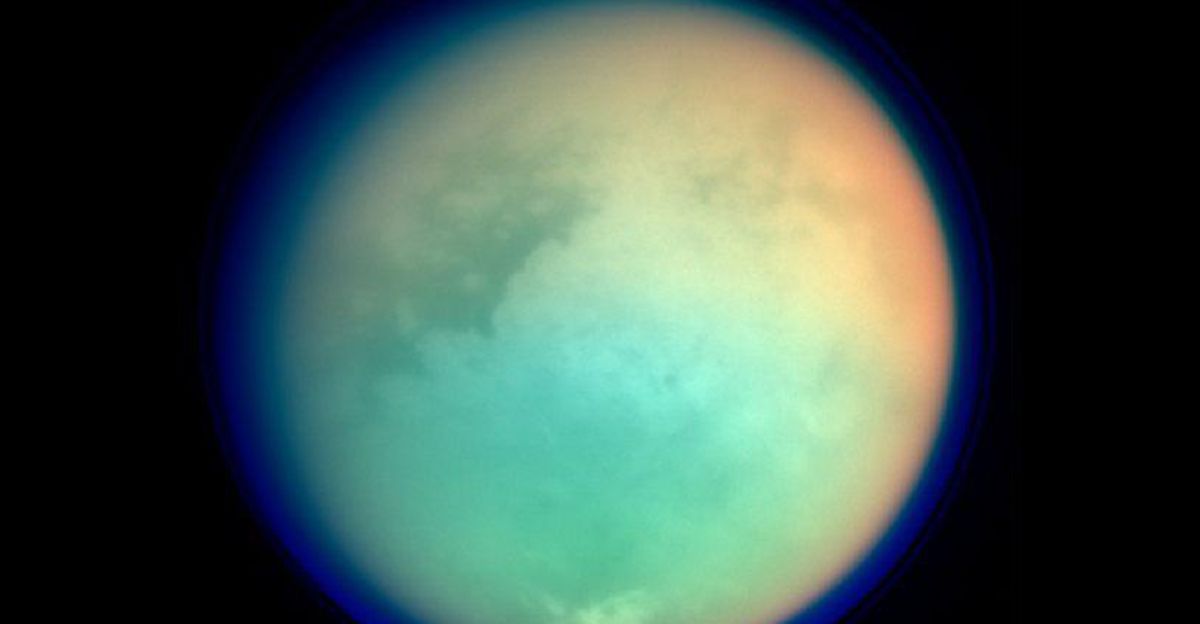

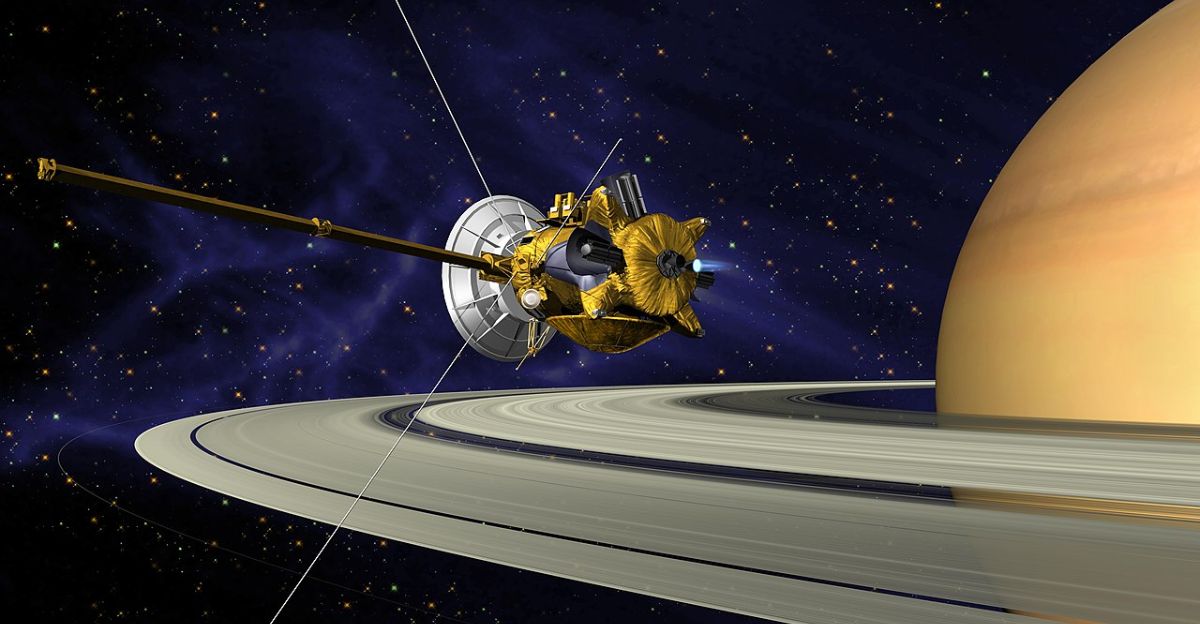

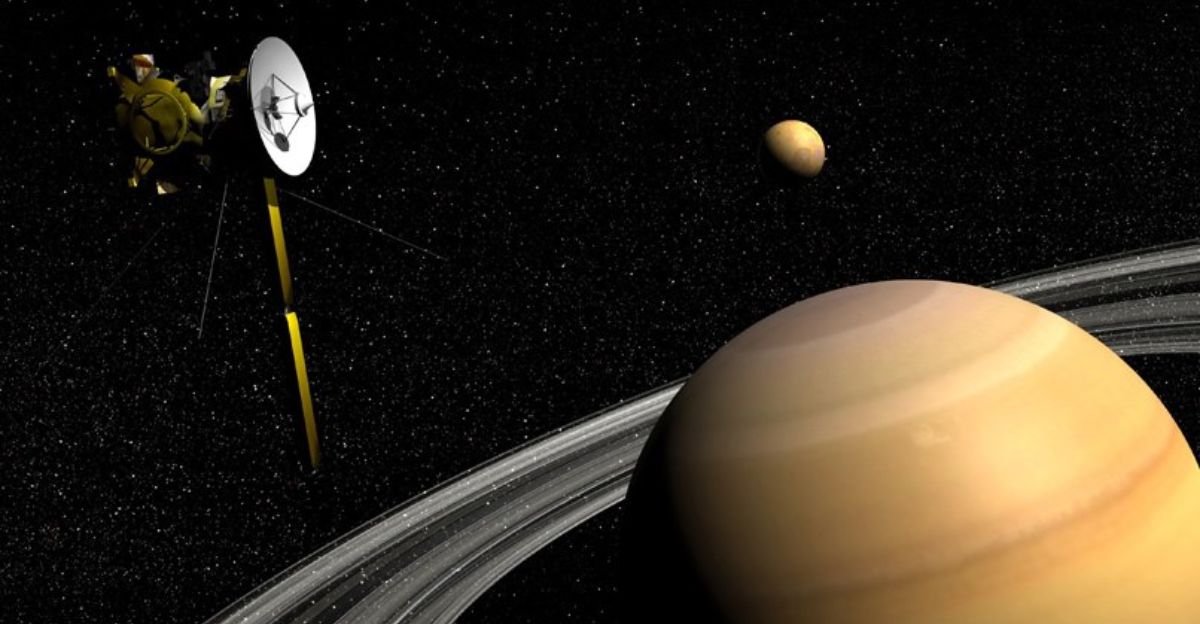

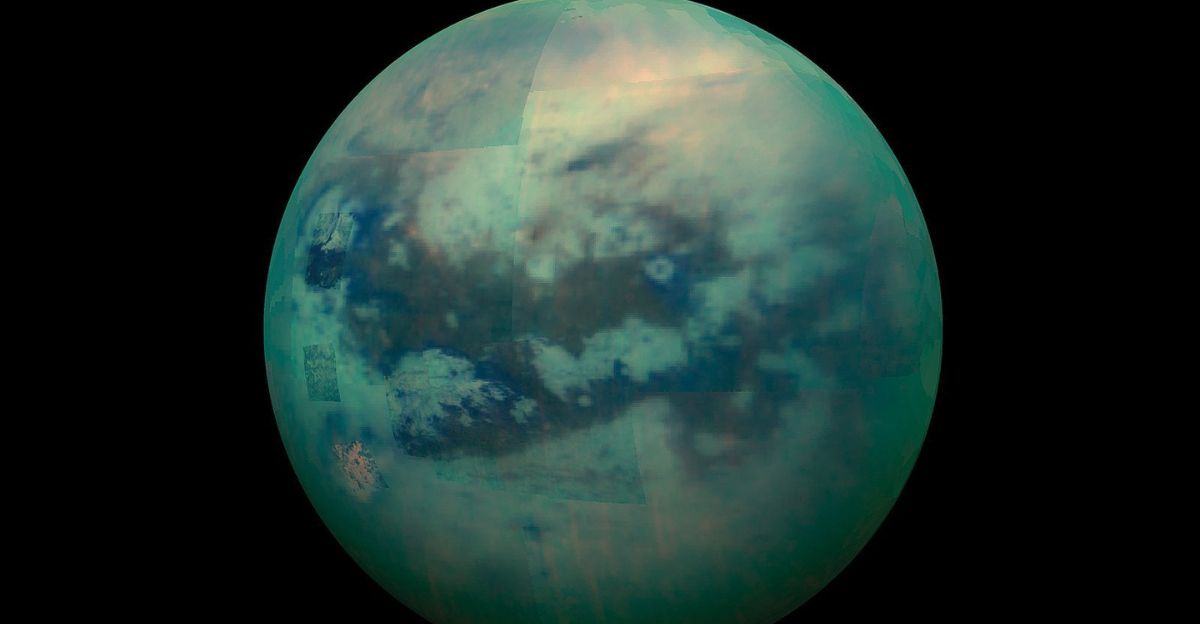

Since January 2008, scientists have believed Titan possesses a global subsurface ocean beneath 50–80 kilometers of ice. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, orbiting Saturn from 2004–2017, collected 635 gigabytes of data from 127 Titan flybys, seemingly confirming this model.

Researchers relied on Cassini’s gravity measurements, which showed Titan’s interior deforming like a water-filled balloon. Yet this certainty rested on incomplete analysis. However, subtle clues would soon overturn decades of assumptions.

The Smoking Gun: A 15-Hour Delay

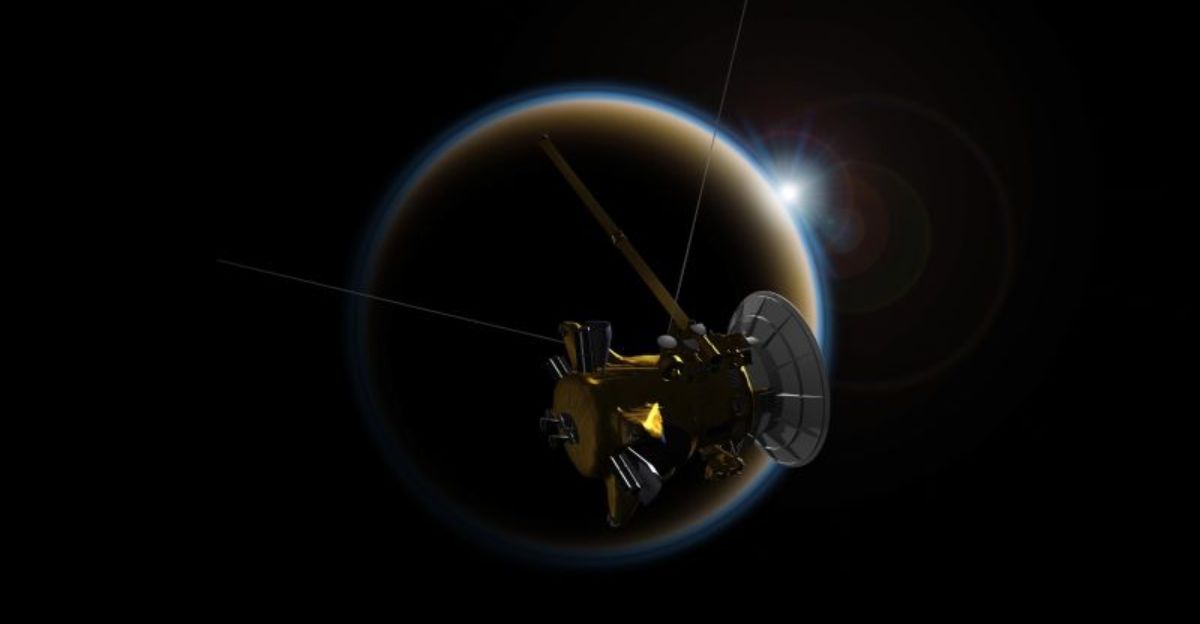

Researchers discovered a 15-hour lag in Titan’s tidal response to Saturn’s gravity. When Saturn passes overhead, Titan’s ground rises with delay, like a time-delayed echo. This lag signals viscous, slushy material, not liquid water.

Lead researcher Flavio Petricca explained: “By reducing the noise in the Doppler data, we could see these smaller wiggles emerge. That was the smoking gun that indicates Titan’s interior is different,” per NASA’s December 17, 2025 announcement. The tidal signature had been hiding in plain sight for 8 years.

Processing Power Finally Catches Up

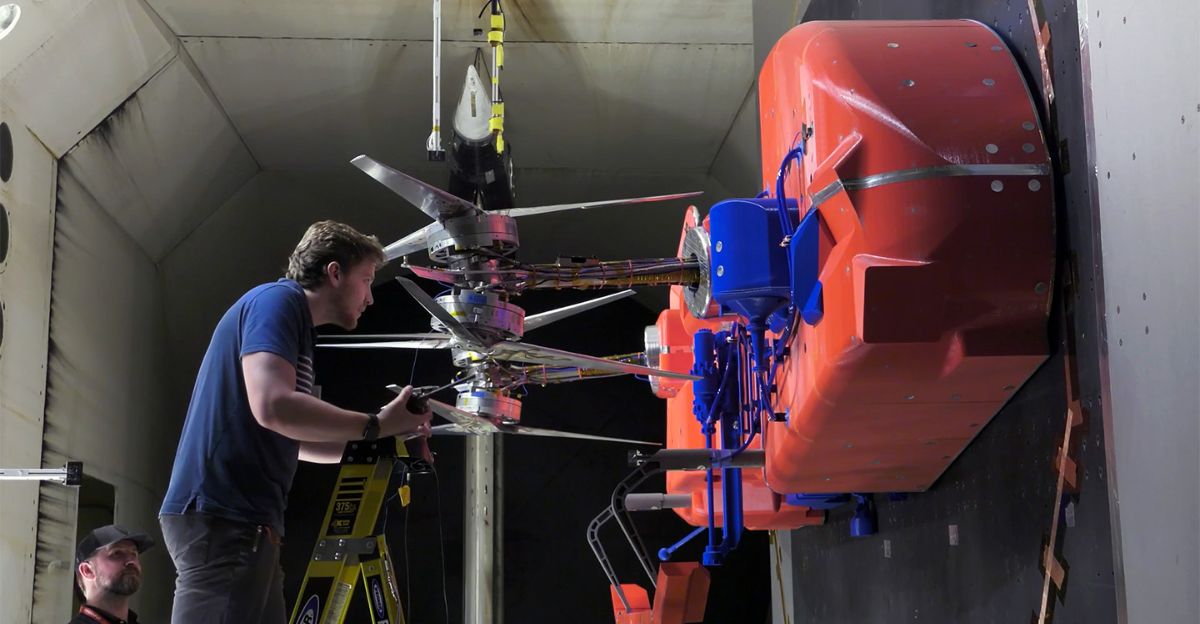

The 2025 discovery relied on new analysis techniques, not new data. Cassini’s radio receiver recorded raw Doppler signals over 13 years, but averaging over 60 seconds hid subtle phase lags. Researchers applied open-loop methods from NASA’s Juno and InSight missions, recovering 1-second-resolution measurements. Phase-averaging algorithms reduced thermal noise by 25–30% per flyby. This leap unlocked a discovery window that had been sealed since Cassini’s instruments fell silent in September 2017. Sometimes, technology lets us see what was always there.

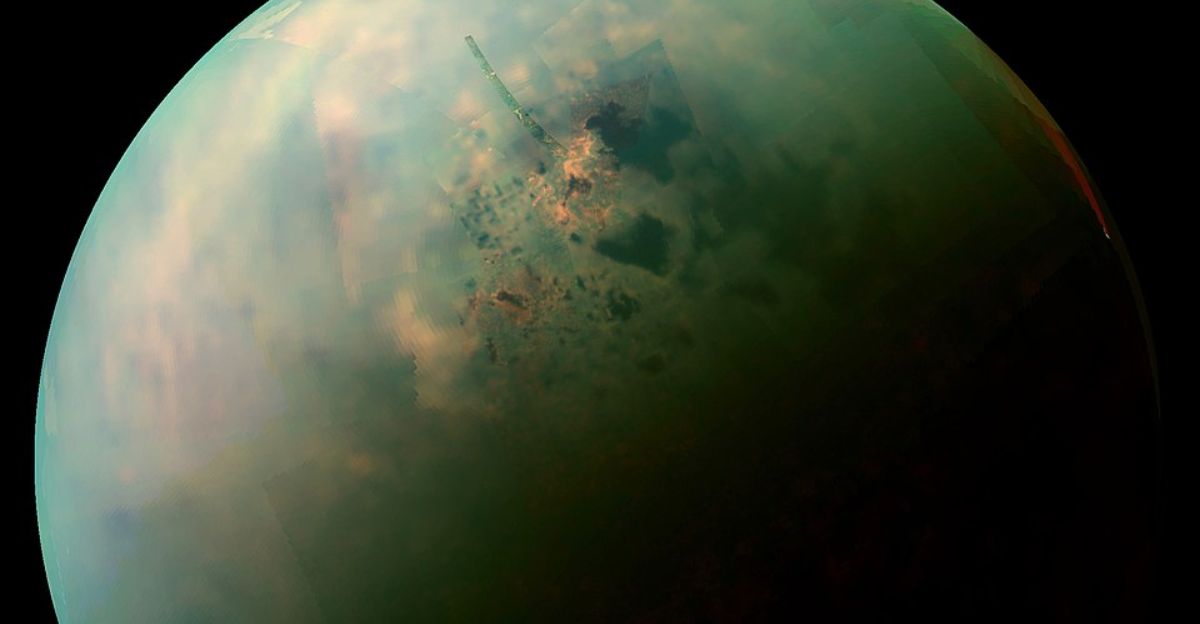

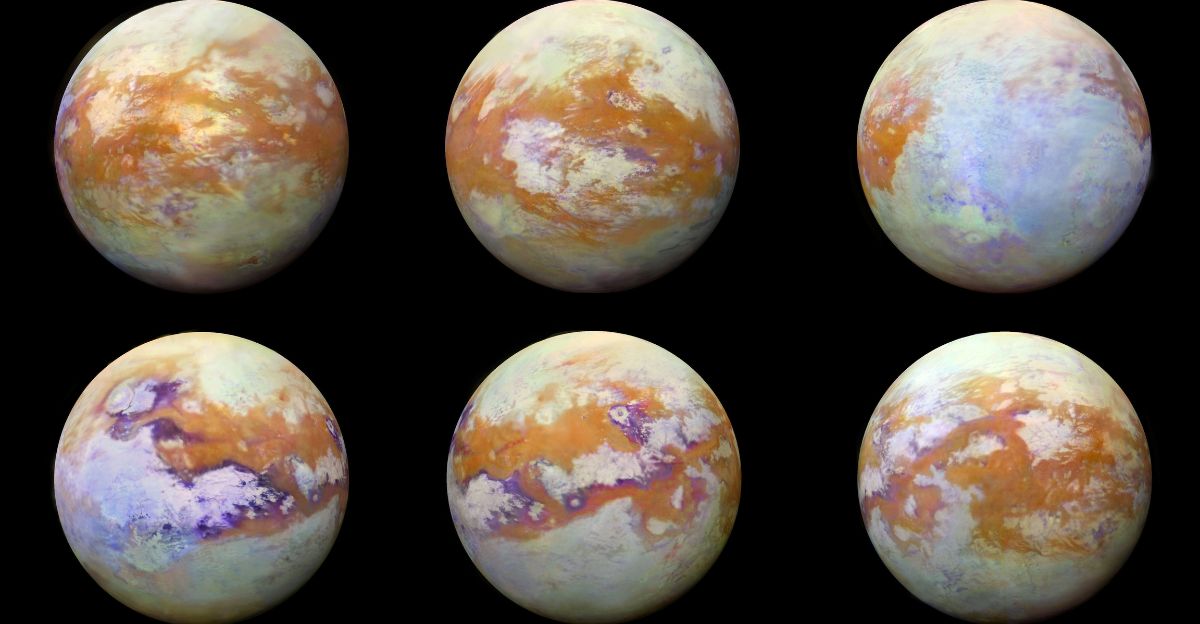

The Interior Revealed: 550 Kilometers of Exotic Ice

Titan’s new model shows a 550-kilometer-deep hydrosphere of high-pressure ice polymorphs—Ice III, V, and VI—under extreme conditions. Above lies a 170-kilometer shell of conventional ice, below a low-density rocky core. Countless pockets of liquid water reach 20 degrees Celsius (68 Fahrenheit). These pockets allow concentrated chemistry in ways a global ocean never could. This slushy architecture reshapes how scientists view potential life. The discovery challenges assumptions and redirects astrobiology toward these isolated environments.

“Different Environments Within Extraterrestrial Worlds”

Flavio Petricca summarized the shift: “The biggest implication of this finding is the existence of very different environments within extraterrestrial worlds, compared to what we thought a few years ago,” according to a December 17, 2025, Nature publication. Slushy hydrospheres with isolated water pockets may be more common across the solar system than assumed, redefining astrobiology priorities. “While Titan may not possess a global ocean, that doesn’t preclude its potential for harboring basic life forms. It makes Titan more interesting,” Petricca added.

The Energy Dissipation That Changed Everything

Titan dissipates ~4 terawatts of tidal energy internally—far exceeding a global ocean’s 0.5–1 terawatt. Viscous friction in a 378-kilometer ice layer explains this energy budget. Titan’s tidal quality factor (Q = 4.5 ± 1.1) is 67 times more intense than Earth’s mantle (Q ≈ 300). Heat generated by friction keeps isolated water pockets liquid despite Titan’s frigid environment. The energy numbers revealed the limitations of the old ocean model. This evidence fundamentally reshapes the understanding of Titan’s interior.

Concentration Over Dilution: Why Isolated Pockets May Be Better

Previously, scientists assumed a global ocean maximized habitability. New analysis shows isolated water pockets concentrate salts and organic molecules. Baptiste Journaux explained: “Pockets of liquid water embedded in the ice can concentrate salts and organic molecules, creating chemically rich liquid solutions. Strong convection connects the rocky floor with surface organics.” Concentrations reach 100–1,000 mg/L, compared to Earth’s ocean, which ranges from 1–10 mg/L. In this slushy realm, chemistry accelerates, boosting chances for life-supporting reactions. Concentration may trump volume.

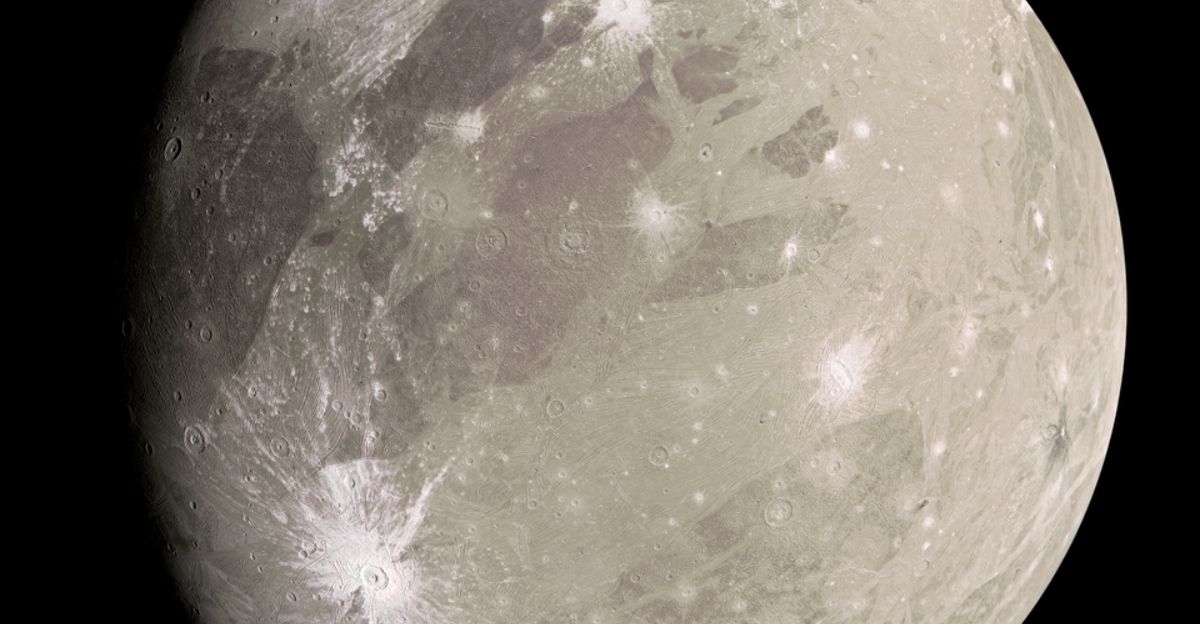

Ganymede at the Crossroads: A Cosmic Mirror

Jupiter’s Ganymede parallels Titan. Once likely an ocean world, it may be freezing due to declining tidal heating. “There is a threshold between a large icy satellite and an ocean world, and if Titan, like Ganymede, once had an ocean, the dissipation of the energy deposited by Saturn is insufficient to prevent its progressive freezing,” per Nature, December 17, 2025. This reframes Ganymede as ambiguous, unlike Europa and Enceladus, which retain ocean worlds. Titan’s transformation hints at evolutionary diversity among icy moons.

The Cassini Legacy: Data That Outlives Missions

The Cassini-Huygens spacecraft cost $3.9 billion ($2.5B development, $704M operations, $54M Deep Space Network). Operating 1997–2017, its data continues yielding discoveries. Reanalysis in 2025 reveals that archival data can uncover truths overlooked in the initial analysis. “The data these amazing spacecraft collect lives on, so discoveries can be made years, or even decades, later as analysis techniques get more sophisticated.” Few investments in exploration offer such long-term returns. Titan’s secrets had been waiting patiently.

When Did Titan’s Ocean Freeze? The Timeline Question

Titan’s past ocean likely froze over 1–2 billion years ago. Rosaly Lopes noted: “This analysis focuses on Titan’s present state, but it’s very likely that in the past there was indeed an ocean of liquid water that froze over time.” Cooling of high-pressure ice and orbital dynamics suggest a transition to a slushy hydrosphere. Could life have emerged in the ancient ocean? Evidence may await Dragonfly’s mission. The timeline compresses potential abiogenesis into a geologically brief period.

Surface Methane Lakes Hold a Chemical Clue

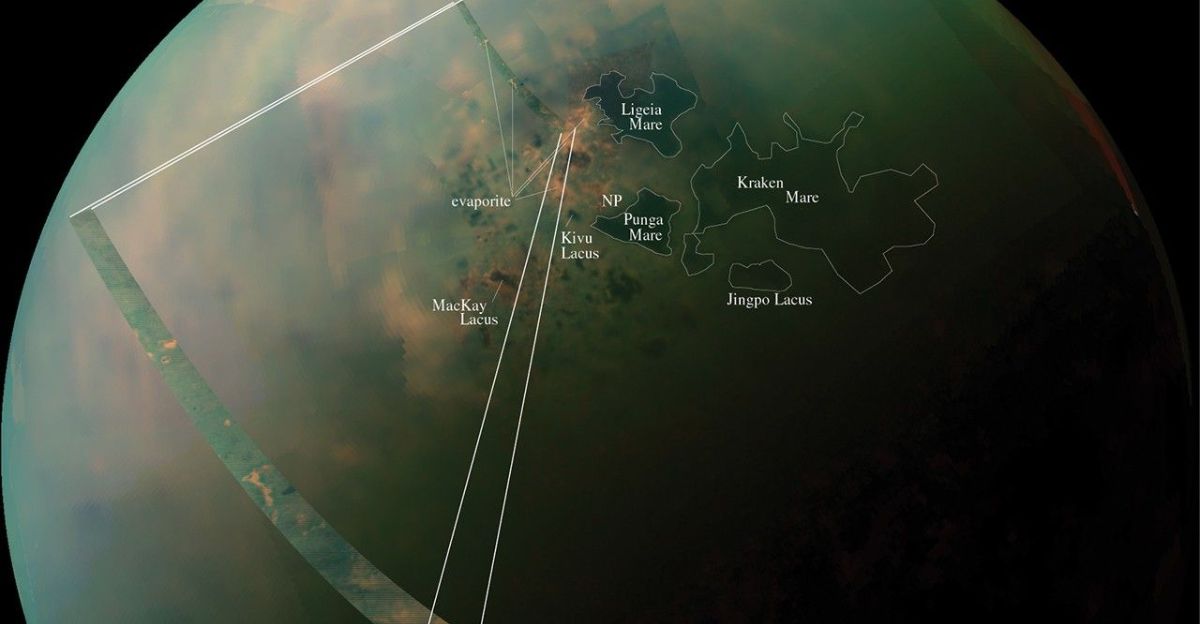

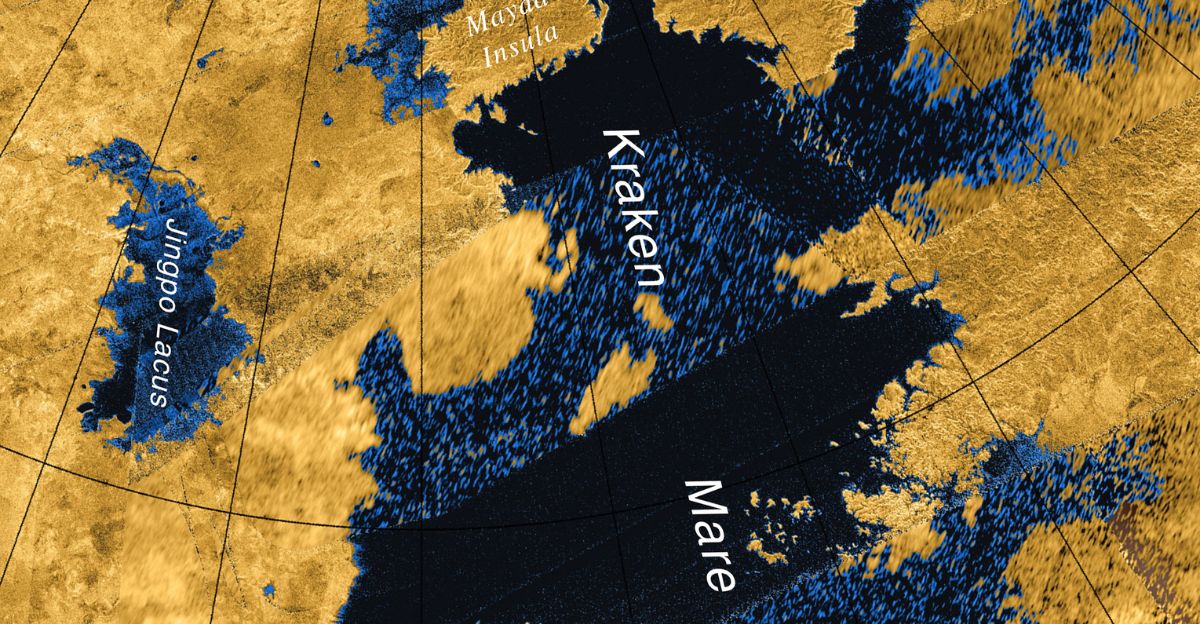

Titan’s methane and ethane rain collects in lakes 300 times larger than Earth’s hydrocarbon reserves. Kraken Mare exceeds the Caspian Sea. UV-driven photochemistry produces tholins raining onto the surface. These hydrocarbons exist at -179 Celsius, too cold for life. Warm water pockets beneath ice offer a chemical bridge, connecting surface organics to liquid water in habitable conditions. The 2025 Nature study highlights this vertical connectivity. Titan’s slushy interior uniquely allows surface chemistry to interact with potential habitats beneath.

“Very Likely” a Past Ocean: Accepting Uncertainty

Rosaly Lopes reframed ancient oceans as history, not present reality. She said, “Warm ice increases the chances of bacteria being able to survive in these environments. In an open ocean, organic material would be very diluted, while in these pockets it would be much more concentrated.” The slushy model enhances chances for microbial detection. Good science integrates new evidence without discarding prior possibilities. Titan may now represent a richer laboratory for life than previously imagined.

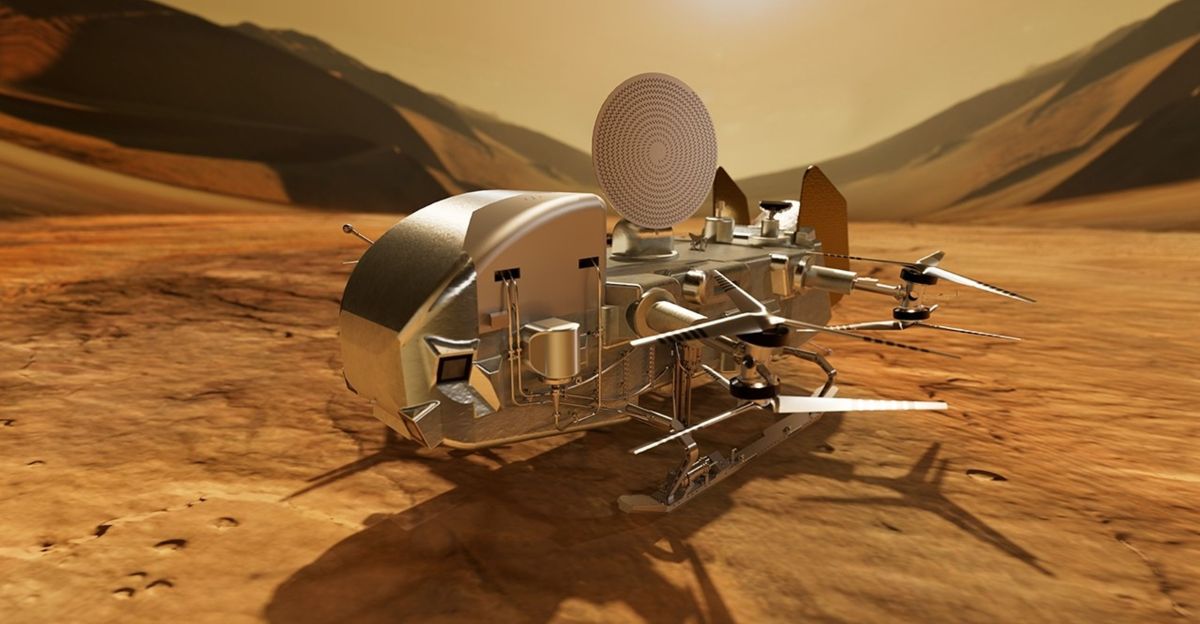

Dragonfly Arrives in 2034: The Ultimate Test

NASA’s Dragonfly mission is scheduled to launch in July 2028, with a planned arrival at Titan in 2034. Costing $3.35 billion (~3.2B euros), it is one of NASA’s largest planetary missions. Dragonfly carries a seismometer to map subsurface water pockets. Over 100 flights will analyze slushy ice and liquid interfaces. Seismic imaging will confirm or refute isolated water pockets theorized by the 2025 reanalysis. Dragonfly shifts the hunt from speculation to observation. Titan’s interior mysteries will finally be subjected to direct measurement.

Seismic Mapping: How Dragonfly Will Peer Inside

Dragonfly’s seismometer will analyze waves from impacts, eruptions, and convection to map subsurface layers. Differences in velocity between liquid water (~1.5 km/s) and ice (~3.5–4 km/s) enable depth mapping. Baptiste Journaux said: “The watery layer on Titan is so thick, the pressure is so immense, that the physics of water changes. Water and ice behave differently than seawater here on Earth.” Seismic data will transform theoretical models into observable reality. Titan’s secrets will finally be directly imaged.

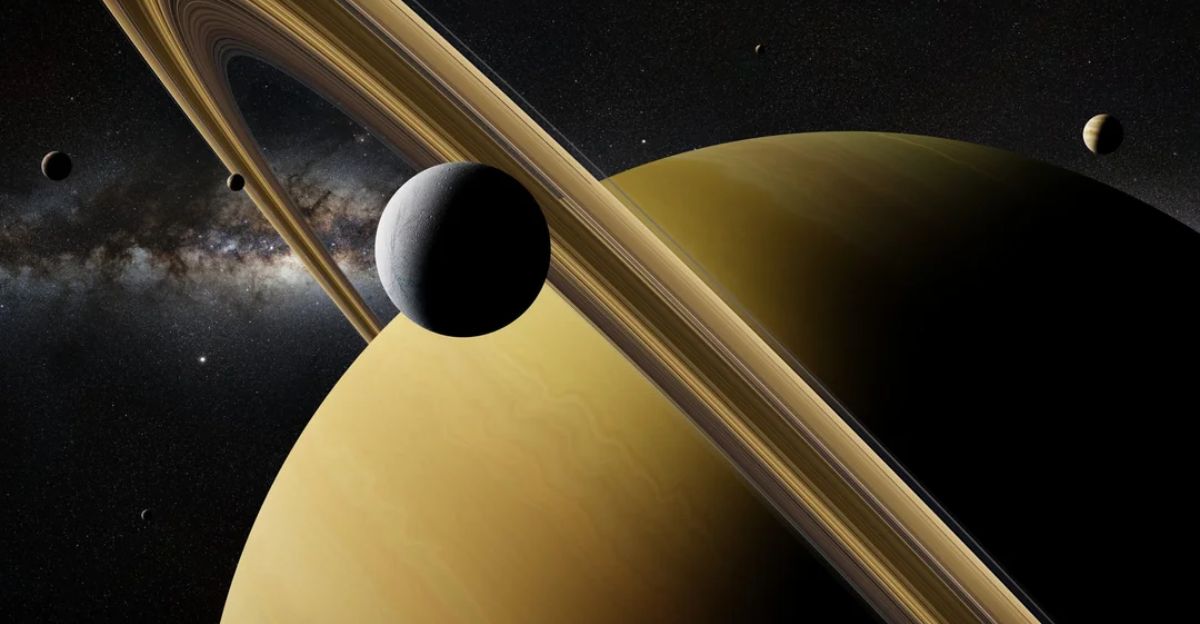

Orbital Mechanics Reveal Deep Time

Titan drifts outward from Saturn at 11 cm/year. In ~30 million years, its orbit will circularize, tidal heating will fade, and the slushy hydrosphere will cool. This constrains Titan’s habitability window. Earth’s earliest microbial fossils date to 3.5–3.8 billion years ago. If Titan’s pockets formed within 1.3 billion years, the time for abiogenesis was brief but plausible. Orbital mechanics dictate that life opportunities are finite, emphasizing urgency for current missions. Timing is critical in understanding Titan’s potential for life.

Europa Clipper and the Ocean World Crisis

Titan’s reanalysis affects other icy moons. Europa Clipper, launched October 14, 2024, will arrive at Jupiter in April 2030. Its $1.6 billion mission (1.5B euros) may face similar slushy pockets if Titan’s dissipation model applies. Ice shell fragmentation could replace a global ocean. The 2025 study challenges assumptions about ocean-world stability. Persistent global oceans may be rare among large icy moons. Comparative planetology must reconsider the habitability of these worlds. Titan now serves as a reference for the evolution of other satellites.

Exoplanets: Slushy Worlds Everywhere?

Exoplanets orbiting M-dwarfs may undergo extreme tidal heating, ranging from 100 to 1,000 terawatts, depending on their mass and orbit. Petricca shows intense heating generates viscous ice friction, producing slushy hydrospheres with isolated water pockets. Global oceans may be rare.

Such slushy interiors could be common among massive icy exoplanets, expanding astrobiology targets. Concentrated pockets, not oceans, may dominate habitable chemistry. Fragmented, slushy niches may define life-friendly planets, suggesting the universe favors chemical concentration over homogeneous oceans. Titan provides a blueprint.

The Dragonfly Cost Overrun Justified by Science

Dragonfly’s budget grew from $850 million in 2019 to $3.35 billion by 2025. NASA critics cited cost, but the 2025 Petricca findings justify the increase. The seismometer payload is essential for mapping subsurface water pockets. Revised planning emphasizes seismic tomography as a primary goal.

Expanded scope ensures answers to Titan’s fundamental questions. The cost-per-question ratio improves when objectives are specific and scientifically justified. The budget now reflects necessity rather than excess. Dragonfly’s mission is both ambitious and critical.

The Concentration Paradox: More Life in Less Water?

Traditional astrobiology favored large oceans as ideal habitats. Titan’s pockets invert this logic. Saltwater pockets at 100–1,000 mg/L organic carbon may support more productive microbes than Earth’s oceans (2–5 mg/L). Polar sea ice ecosystems show that concentrated brine pockets boost productivity.

Journaux noted: “Pockets of liquid water embedded in the ice can concentrate salts and organic molecules, creating chemically rich liquid solutions.” Titan’s isolated chambers may sustain richer chemistry than a global ocean. Fragmentation may enhance, rather than limit, life potential.

The Hunt Transforms: Slushy Worlds as Life’s Frontier

The December 17 reanalysis shifts focus from oceans to slushy hydrospheres with concentrated pockets. Dragonfly now emphasizes mapping and chemical analysis. Ganymede may follow Titan’s freezing pattern. Europa and Enceladus remain ocean-world targets, but life’s potential venues are more diverse. Petricca concluded that “The biggest implication is the existence of very different environments within extraterrestrial worlds.” Chemistry thrives in fragmented niches, not just endless seas. The hunt for life expands dramatically, redefining the priorities of astrobiology.

Sources:

“Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean,” Nature, December 17, 2025.

“NASA Study Suggests Saturn’s Moon Titan May Not Have Global Ocean,” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, December 16, 2025.

“NASA Discovers Titan Doesn’t Have an Ocean, But a ‘Slushy Ice Layer,” El País (English), December 17, 2025.

“Saturn’s Moon Titan May Not Have Buried Ocean as Suspected,” PBS NewsHour, December 17, 2025.

“Titan Might Not Have an Ocean After All,” Science Magazine, December 16, 2025.

“NASA’s Dragonfly Rotorcraft Mission to Saturn’s Moon Titan Confirmed,” NASA Science Mission Directorate, April 16, 2024.