For 4,500 years, a ceramic pot buried in Egypt’s sand held a secret. Inside lay a skeleton whose DNA transforms how we understand the ancient world. Scientists long believed Egypt’s early people stayed isolated in the Nile Valley.

Yet this labourer’s bones reveal genetic markers from three continents, hinting at vast human networks that scholars barely imagined. His DNA will overturn ideas held since Petrie first dug Egyptian remains.

The 40-Year Quest

Egypt’s climate destroys DNA relentlessly through heat, humidity, and time. For 40 years, researchers tried the impossible: extracting a complete genome from the harsh Nile Valley. Bones crumbled, proteins broke down, and genetic material became useless fragments.

Nobel laureate Svante Pääbo attempted extraction in the 1980s, but all projects failed. Year after year, conference after conference, the barrier held firm. By 2024, many labs surrendered. Then Liverpool’s modest museum collection revealed an unexpected level of preservation.

A Potter’s Tomb

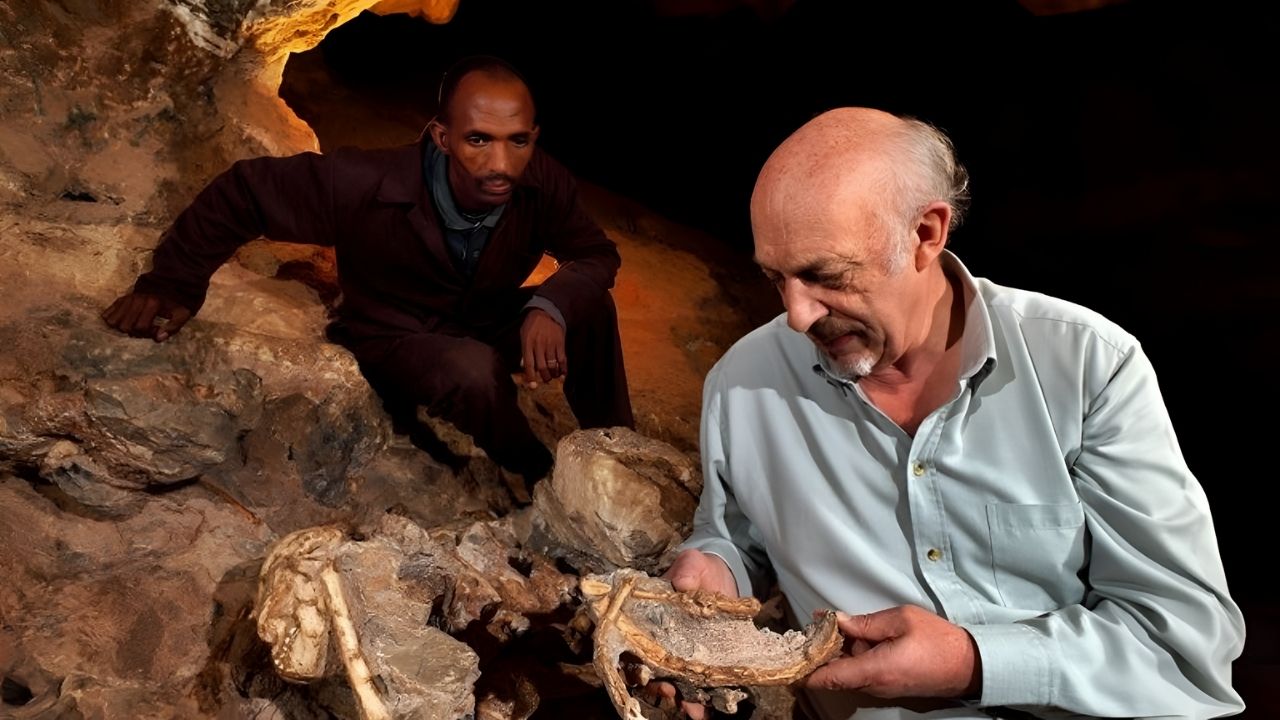

Scientists discovered the skeleton at Nuwayrat, a burial site located near Beni Hasan, approximately 165 miles south of Cairo. Excavators unearthed it in 1902, and it has been on display in Liverpool’s World Museum for over 100 years.

The man was 44–64 years old and was buried in a ceramic pot—an unusual practice. His bones revealed decades of hard work, with worn joints and muscle stress. Yet his tomb placement suggested high status. Radiocarbon dating: 2855–2570 BCE, the Old Kingdom.

Why This Skeleton Mattered

Most Egyptian burials destroy DNA within centuries. Tombs expose remains to moisture, insects, and temperature fluctuations that can break down DNA. However, this potter’s ceramic vessel created a sealed and insulated microenvironment.

Scientists extracted samples from two molars—teeth’s hard enamel shields inner pulp longer than any bone does. The Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University recognised an unprecedented chance: the first opportunity to sequence a complete ancient Egyptian genome.

The Genome Reveals

When researchers decoded the genome, it shattered every assumption. The man carried roughly 80% North African ancestry, matching Neolithic Morocco populations 930 miles across the desert.

Notably, 20% came from the Fertile Crescent, the region that includes Mesopotamia and early agricultural settlements. Scientists compared his DNA with over 1,500 reference samples spanning millennia.

The data showed no doubt: this Old Kingdom man carried genetic ancestry from two ancient worlds rarely thought to mix, closing a 1,300-year gap.

The North African Connection

The 77.6–80% North African ancestry didn’t come from Egypt’s river communities. Instead, genetic analysis matched Neolithic populations from today’s Morocco—people living 7,000 years before this potter was born.

This wasn’t fresh mixing; it showed deep ancestral links. Egypt’s origins reframed: Old Kingdom society didn’t grow purely locally, but rather inherited genetic traits from North African hunter-gatherers and early farmers across the Maghreb.

Earlier scholars theorised such connections through pottery and trade goods. DNA proved it in genetic sequences.

The Mesopotamian Mystery

The 20–22% Fertile Crescent ancestry posed a profound puzzle: how did a man buried in Egypt 4,500 years ago carry genetic signals from Mesopotamian farmers? Direct migration over 930 miles was possible but demanding.

Archaeological pottery didn’t show long-distance trade; most Mesopotamian contacts seemed fragmented and rare. Yet genetic evidence emerged—clear and measurable. His isotope ratios proved he grew up in the Nile Valley.

This meant an ancestor descended from Mesopotamia. Network historians underestimated what likely existed.

Sub-Saharan Ancestry Gap

Today’s Egyptians carry 14–21% sub-Saharan African ancestry—starkly different from this Old Kingdom man’s zero detectable sub-Saharan DNA.

This gap reveals a crucial historical shift: substantial gene flow from south of the Sahara happened after the Old Kingdom fell, probably during Rome’s era or later. Early pharaonic Egypt looked genetically different from modern Egyptians.

The ancestry makeup shifted dramatically—not through population replacement, but through centuries of migration and mixing. This potter represents pre-Roman Egypt genetically.

The Labour of Kings

Skeletal analysis revealed his working life. Stress marks, worn joints, and muscle attachment sites indicated decades of hard manual labour—possibly pottery production, given the quality of the burial vessel.

Yet his tomb position and burial goods suggested high status. He wasn’t a slave or a king but a valued expert: a skilled labourer important enough for a high-status burial. His hands paid the cost.

Isotope analysis of tooth enamel confirmed the Nile Valley origin of birth and childhood food. His entire life unfolded in Egypt.

The Migration Question

This finding reshapes migration theory fundamentally. Scholars debated whether Egypt-Mesopotamia contact meant trade alone or the actual movement of people. This genome provides the first solid genetic evidence: humans migrated between regions.

The man didn’t originate in Mesopotamia himself—his parents or grandparents did. This indicates that migration occurred one or two generations prior to his birth, suggesting established networks rather than rare meetings.

Mesopotamian traders perhaps settled Egypt. Egyptian expeditions perhaps brought back families. Population drift may have crossed the Levant. People, not just goods, moved.

The Knowledge Crisis

Before this discovery, Egyptian history relied on three primary sources: hieroglyphic records, archaeological artefacts, and occasional skeletal remains. All three had serious limits.

Hieroglyphics emphasised royal propaganda; artefacts showed trade but not migration; skeletons revealed little without DNA analysis. Population origins remained a matter of guesswork. Egyptologists built narratives from silence. Some theorised Levantine origins; others argued local development; few considered Moroccan connections without direct proof.

This genome ended guessing. It delivered a verifiable scientific baseline. Suddenly, hundreds of unanswered questions became testable puzzles.

The Preservation Paradox

Ironically, this breakthrough needed a failure. If Egypt’s climate had treated the DNA kindly, perhaps a less remarkable skeleton sequenced first would spark fewer questions. Instead, extreme difficulty meant only an exceptional specimen could yield results.

The potter’s ceramic creation brought about that miracle. Egypt’s harsh environment, which degrades most remains quickly, forced scientists to focus on the best-preserved examples.

The result: the first Egyptian genome came from someone particularly significant, whose mixed ancestry revealed population insights immediately. Rarity concentrated meaning dramatically.

The Regulatory Path Forward

The Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University published in Nature, with complete genomic data released to public databases for independent review.

The UK’s Natural Environment Research Council funded the research, showing institutional commitment to ancient DNA archaeology. Importantly, Egyptian antiquities authorities permitted excavation analysis and international publication—a significant shift from earlier rules that prohibited the removal of cultural materials.

This collaborative model, which combines British institutions, Egyptian authorities, and international databases, sets a precedent for future ancient DNA projects across Africa and the Middle East.

The Next 100 Genomes

Researchers stress that one genome, however remarkable, cannot define an entire civilisation. Lead author Dr Adeline Morez Jacobs states: “Many more individual genome sequences are needed to fully understand variation in ancestry in Egypt at the time.”

Teams plan to sequence remains from other Beni Hasan burials, Middle Kingdom sites, and New Kingdom contexts. Each genome should clarify whether this Potter represents typical Old Kingdom ancestry or an unusual case.

Early evidence suggests considerable genetic diversity even within elite burial groups.

The Broader Implications

This discovery raises urgent questions about ancient migrations across Eurasia. If Mesopotamian ancestry reached Egypt 4,500 years ago, where else did these populations travel? What impact did Fertile Crescent farmers have on North African societies? How wide were Bronze Age movement patterns? Were migration networks far more intricate than written records show?

These questions now drive funding toward systematic ancient DNA sampling across North Africa, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia. Scientists aim to reconstruct population movements over millennia, thereby revealing patterns of cultural exchange and biological mixing.

Emerging Research Pathways

Liverpool John Moores researchers have identified a second candidate skeleton from Beni Hasan, showing promising signs of preservation. Meanwhile, ancient DNA labs at Uppsala and Beijing universities requested samples from the Egyptian museum collection to establish international research partnerships.

The Nature publication sparked a wave of grant applications: the European Molecular Biology Organisation solicited proposals for “Ancient Mediterranean Genomics”; the National Science Foundation allocated $12 million toward similar projects in Southwest Asia.

New publications show Mesopotamian genetic signals in Bronze Age Anatolian samples, suggesting broader networks.

Agricultural Revolution Connections

If Mesopotamian ancestry reached Egypt through population movement, those migrants probably carried agricultural technologies, domesticated animals, and religious ideas.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Egyptians adopted Mesopotamian-style beer brewing, certain crop varieties, and architectural styles during the Old Kingdom. Scholars previously debated whether these represented trade or cultural borrowing.

Genetic evidence now suggests both: actual population movement carrying not just concepts but living agricultural traditions. This pattern repeats across ancient civilisations: the spread of farming to Europe, East Africa, and South Asia involved demographic change alongside technological transfer.

Public Perception and Misinformation

Social media has already misused this discovery. Some commentators claim it “proves” ancient Egypt was fundamentally Mesopotamian—false. Others say it undermines African civilisation’s contributions—also false.

Reality: One individual’s mixed ancestry reflects the normal human migration process. Experts stress that 80% North African ancestry clearly establishes primary roots.

The 20% Mesopotamian element enriched rather than dominated. Yet YouTube videos and viral posts misrepresent findings badly. Museums, universities, and Nature issued clarifications. Open data access helps counter misinformation, allowing researchers to verify claims independently.

Historical Precedent

Ancient DNA discoveries have repeatedly overturned conventional historical narratives. The Ötzi mummy revealed a trans-Alpine migration 5,000 years ago; Viking DNA showed extensive settlement in North America; early American genomics revealed multiple founding populations.

In each case, genetic evidence forced scholars to reconsider migration patterns, trade routes, and population continuity. Yet patterns emerged: genetic evidence rarely contradicts well-established archaeological data; instead, it adds human demographic detail to material culture records.

Egypt’s case follows this trajectory. Archaeological evidence already documented Egypt-Mesopotamia contact; DNA confirms humans participated in these exchanges.

The Bottom Line

A single potter buried 4,500 years ago in ceramic became the first window into ancient Egypt’s genetic reality. His body revealed that Egypt’s foundational populations were cosmopolitan far earlier than previously believed by historians.

Roughly 80% ancestral heritage is linked to North African communities; 20% to Mesopotamian farmers. This mixture probably characterised Old Kingdom Egypt broadly, suggesting long-distance networks and population movement woven into pharaonic civilisation from the start.

For Egyptology, this shifts fundamental ideas: early Egypt wasn’t isolated but integrated into broader Bronze Age exchange systems.

Sources:

- Nature Journal, “Whole-Genome Ancestry of an Old Kingdom Egyptian,” July 2, 2025

- Liverpool John Moores University News, “Researchers sequence first genome from Ancient Egypt,” July 1, 2025

- Smithsonian Magazine, “Scientists Have Sequenced an Ancient Egyptian Skeleton’s Entire Genome for the Very First Time,” July 6, 2025

- BBC News, “Ancient Egyptian history may be rewritten by a DNA bone test,” July 2, 2025

- New Scientist, “An ancient Egyptian’s complete genome has been read for the first time,” July 2, 2025

- Yabiladi, “New study reveals ancient Egypt’s genetic ties to Morocco’s Neolithic populations,” July 4, 2025