Across southern Brazil and parts of northern Argentina, researchers have identified vast underground tunnels known as paleoburrows. Some extend more than 550 meters long and reach nearly 1.8 meters in height and width—large enough for a human to walk through.

Their smooth walls, arched ceilings, branching layouts, and distinctive claw marks rule out both human excavation and natural geological processes. Evidence instead points to extinct giant ground sloths, making these the largest animal-made burrows ever documented on land.

Historical Discovery

The first modern identification occurred in the early 2000s, when geologist Heinrich Frank encountered a massive tunnel exposed during road construction in Brazil’s Rio Grande do Sul. Initially mistaken for a cave, its unusual shape and markings prompted further investigation.

Over the next two decades, systematic surveys revealed hundreds more. By the mid-2020s, more than 1,500 paleoburrows had been mapped, transforming what was once a curiosity into a major paleontological discovery.

Pleistocene Context

These tunnels date to the Pleistocene Ice Age, which ended about 11,700 years ago. During this period, South America hosted megafauna including giant ground sloths, some weighing up to four tons. Climate instability, temperature extremes, and predator pressure likely encouraged burrowing behavior.

While humans were present in the Americas late in the Pleistocene, most paleoburrows appear to predate widespread human settlement in the regions where the tunnels are found.

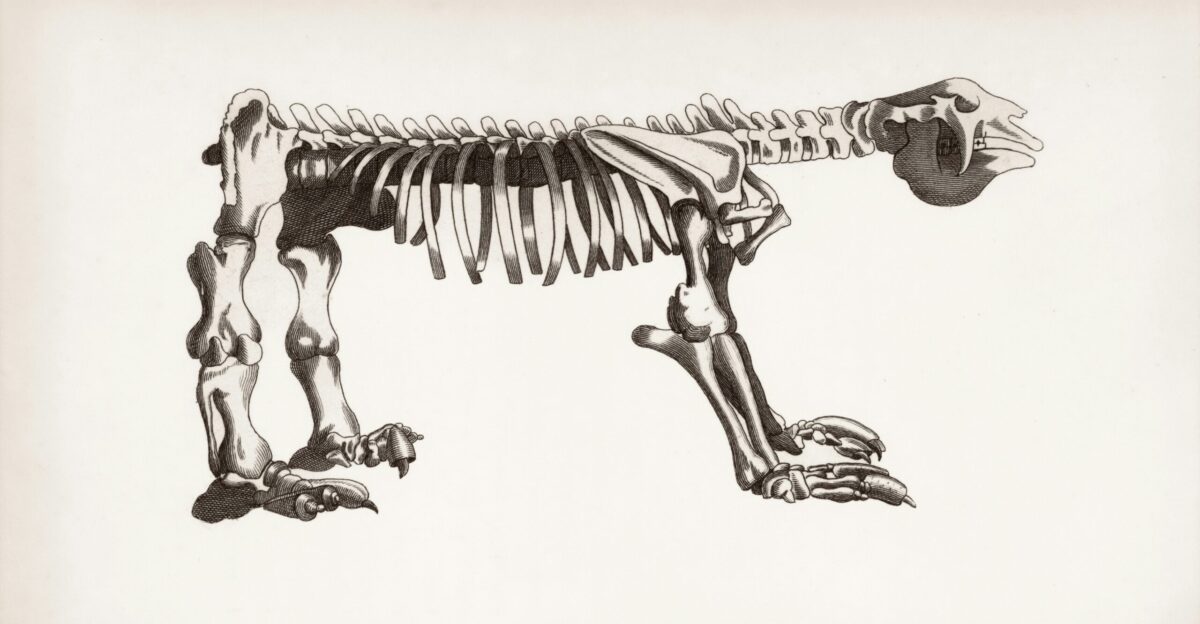

Anatomical Evidence

The internal markings inside paleoburrows closely match the anatomy of giant ground sloths. Broad, shallow claw grooves align with their long, curved forelimb claws rather than the narrow scratches made by smaller burrowing animals.

The tunnels’ elliptical cross-sections—often around 1.5 meters wide and nearly 1.8 meters high—fit the body proportions of large sloths, which could rear upright and brace themselves while digging through compacted sediment.

Rejecting Human Origin

Archaeologists have found no tools, hearths, soot, steps, or cultural debris inside the tunnels. Many date tens of thousands of years earlier than known permanent human occupation of these areas.

Excavating passages hundreds of meters long through hardened sandstone or weathered volcanic rock would have required sustained technology and organization not evidenced in the archaeological record. Fossilized footprints inside the tunnels match sloth anatomy, not human feet.

Dismissing Geological Explanations

Natural caves typically follow fractures, water flow, or chemical dissolution patterns. Paleoburrows do not. They cut across rock layers, ignore fault lines, and show no signs of water erosion, sediment sorting, or lava flow structures.

Instead, walls display consistent claw marks and deliberate shaping. Side chambers and branching corridors further distinguish them from karst caves or lava tubes, reinforcing their biogenic origin.

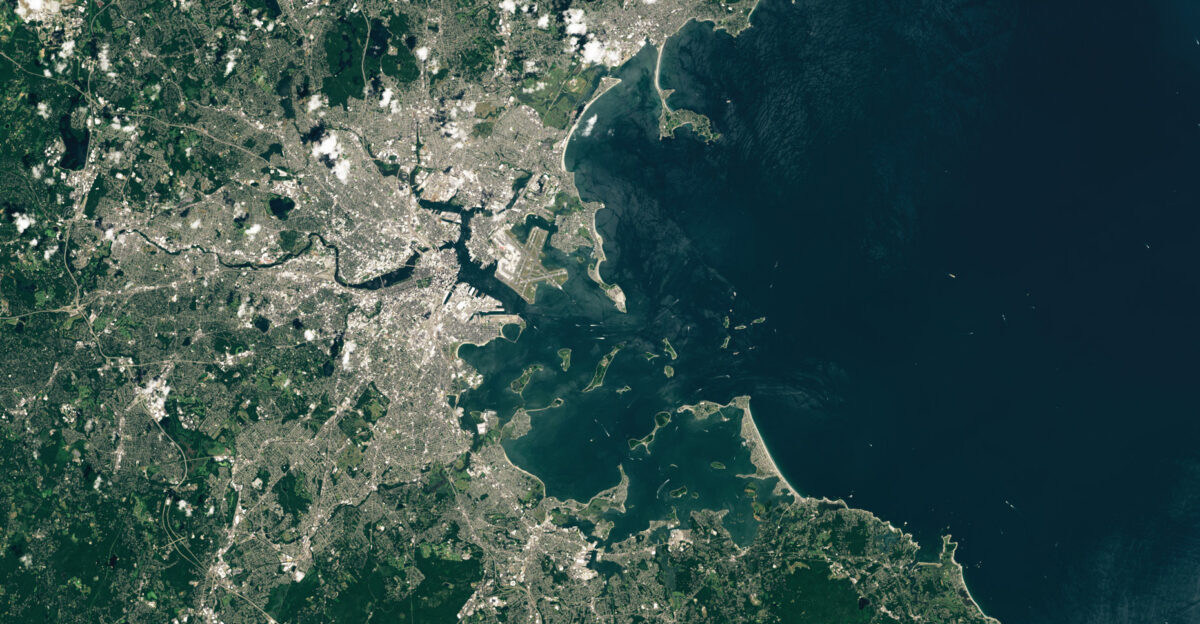

Mapping the Scale

By combining field surveys, road-cut observations, and modern imaging techniques, researchers have mapped extensive tunnel networks. Some regions contain dozens of intersecting burrows within a single square kilometer.

The longest confirmed individual tunnels exceed 550 meters, while clusters form complex underground systems. In total length and volume, these networks rival modern human-made infrastructure, highlighting the extraordinary scale of Ice Age animal engineering.

Ecological Role

Paleoburrows likely played a significant role in shaping Pleistocene ecosystems. By excavating and aerating soil, sloths altered drainage patterns and soil chemistry, influencing plant growth.

The tunnels may have provided stable microclimates for shelter, rest, or protection from predators such as saber-toothed cats. Over generations, repeated use and expansion turned these burrows into long-lasting landscape features.

Modern Research Tools

Recent discoveries have accelerated through the use of drones, LiDAR, ground-penetrating radar, and photogrammetry. These tools reveal hidden entrances, underground extensions, and collapsed sections invisible from the surface.

As development and mining expose more sites, researchers race to document and preserve them. Each newly mapped paleoburrow adds behavioral detail that skeletal fossils alone cannot provide.

Claw Mark Analysis

High-resolution scans of tunnel walls show claw arcs up to 20 centimeters wide, spaced consistently in parallel sets. The depth, curvature, and spacing closely match fossilized claws of giant ground sloths, particularly Megatherium.

Unlike random geological striations, these marks repeat rhythmically over hundreds of meters, indicating sustained, purposeful digging rather than incidental scraping or erosion.

Dating Confirmation

Age estimates come from surrounding sediments, stratigraphic context, and mineral deposits that formed after excavation. Results consistently place the tunnels between roughly 20,000 and 40,000 years old.

This timeframe aligns with the presence—and eventual extinction—of giant ground sloths and predates later human cultures in southern Brazil and northern Argentina, strengthening the case for a megafaunal origin.

Structural Uniformity

Despite being spread across vast regions, paleoburrows share remarkably similar shapes. Most have gently arched ceilings angled to prevent collapse and smooth, compacted floors. This consistency suggests biomechanical efficiency rather than random formation.

The tunnels’ proportions appear optimized for large-bodied diggers repeatedly moving through confined underground spaces over long periods.

Network Density

In some Brazilian states, dozens of tunnels intersect within small areas, forming loops and chambers several meters wide.

Subsurface imaging reveals depths exceeding ten meters in places. Compared to modern animal burrow systems, such as badger setts or wombat warrens, paleoburrow density and scale are orders of magnitude greater, underscoring their uniqueness in the fossil record.

Fossil Footprints

Several paleoburrows preserve fossilized footprints on their floors. These impressions measure up to 30 centimeters long and include drag marks from large claws, matching known sloth trackways from open-air sites.

No confirmed human footprints occur within the tunnels themselves, reinforcing interpretations that the spaces were excavated and primarily used by megafauna rather than people.

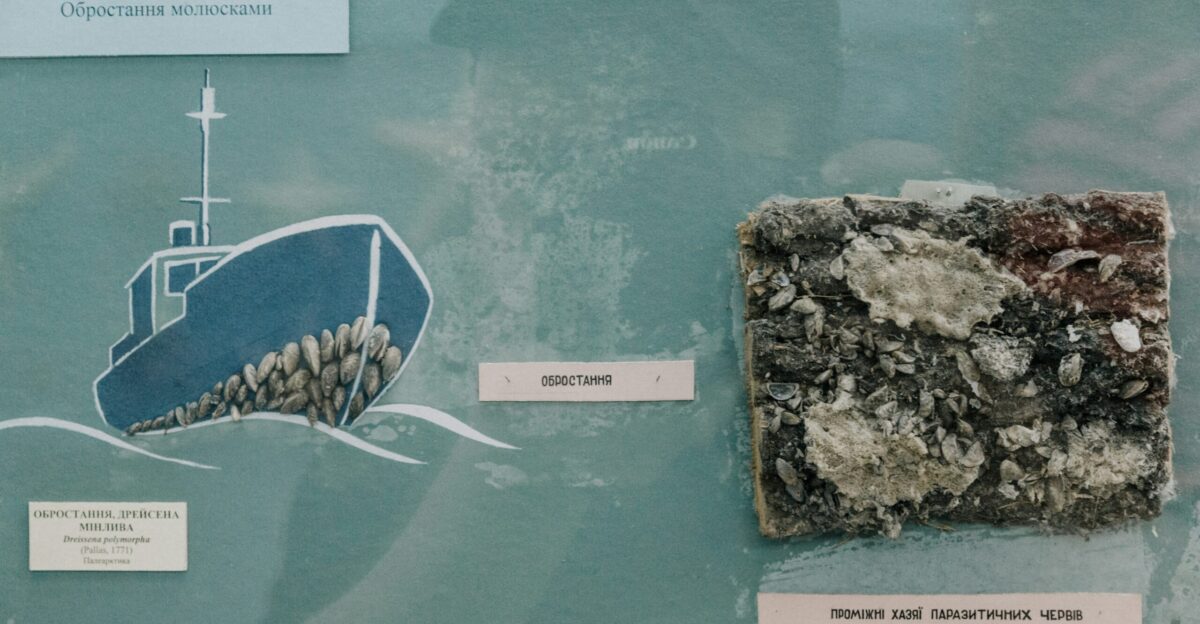

Rock Penetration

The tunnels cut into consolidated sands, sandstone, and weathered volcanic rock—materials far harder than loose soil.

Biomechanical models suggest that repeated claw strikes by multi-ton animals over generations could gradually excavate such substrates. The absence of blasting, fracturing, or collapse patterns typical of geological processes further supports deliberate biological excavation.

Regional Distribution

More than 1,500 paleoburrows have been documented across southern and southeastern Brazil, with additional confirmed sites in northern Argentina.

Their distribution closely overlaps regions rich in giant sloth fossils and is notably sparse in areas dominated by smaller burrowing mammals, reinforcing the link between tunnel presence and megafaunal populations.

Preservation State

Many paleoburrows remain remarkably intact, though entrances are often partially collapsed or filled with sediment deposited after abandonment.

Microscopic analysis of infill material indicates gradual natural backfilling rather than sudden collapse. Approximately 80 percent retain their original morphology, offering rare, well-preserved evidence of extinct animal behavior.

Comparative Sizing

No known living land animal creates burrows approaching this scale. Elephant seal wallows, wombat warrens, and aardvark tunnels are tiny by comparison.

Individual paleoburrow systems may contain thousands of cubic meters of excavated material, making giant ground sloths the largest burrowing land animals ever identified in Earth’s history.

Interaction Evidence

Trackways at White Sands, New Mexico, show humans following giant sloths, stepping into their footprints and provoking defensive behavior. While geographically distant from the South American tunnels, these tracks demonstrate direct human–sloth interaction during the late Pleistocene. Burrows may have served as refuges—or traps—during such encounters, though direct evidence remains limited.

Transformative Legacy

Paleoburrows fundamentally reshape understanding of Ice Age ecosystems. They reveal giant ground sloths as powerful landscape engineers capable of sustained, large-scale excavation.

Neither human activity nor geological forces adequately explain their form, markings, or distribution. Preserved beneath modern hillsides, these tunnels stand as enduring records of megafaunal ingenuity and the hidden behaviors of a lost world.

Sources:

Giant Sloths Crafted 2000-Foot Tunnels Beneath Brazil and Argentina: Scientists Discover

SSB Crack (news.ssbcrack.com)

Huge underground tunnels found in South America were not made by humans—footprints…

Times of India

Turns Out, Humans Didn’t Make These Massive Mysterious Tunnels In South America

The Travel

Giant underground tunnels discovered in South America—Not made by humans or natural forces

Le Ravi