On November 23, 2025, Ethiopia’s Afar region experienced something extraordinary: a volcano awoke after being dormant for longer than human civilization has existed.

The eruption started at 08:30 UTC and sent ash 45,000 feet into the air—high enough to disrupt airplane traffic across three continents within hours. Few people saw this coming. Residents near the Danakil Desert felt shocked.

The eruption arrived without warning, without earthquake alerts, and without the typical signs volcanologists watch for worldwide. This story reveals a geological surprise, an aviation crisis, and uncomfortable gaps in how we monitor Earth’s most remote volcanoes.

Red Sea Disruption Spreads

The ash plume split into two paths: one drifting northeast toward the Arabian Peninsula and another moving northwest toward the Red Sea.

By November 24, satellite images showed that the cloud had crossed Yemen and Oman, moving at speeds of 62–75 miles per hour. The Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre issued urgent warnings throughout the day.

Airlines across the Middle East got notifications. Within 36 hours of the eruption, the ash cloud moved fast enough to create a crisis—commercial aviation from Africa to South Asia faced trouble. Indian airspace will be affected as of the next business day.

The Rift Valley’s Geological Lottery

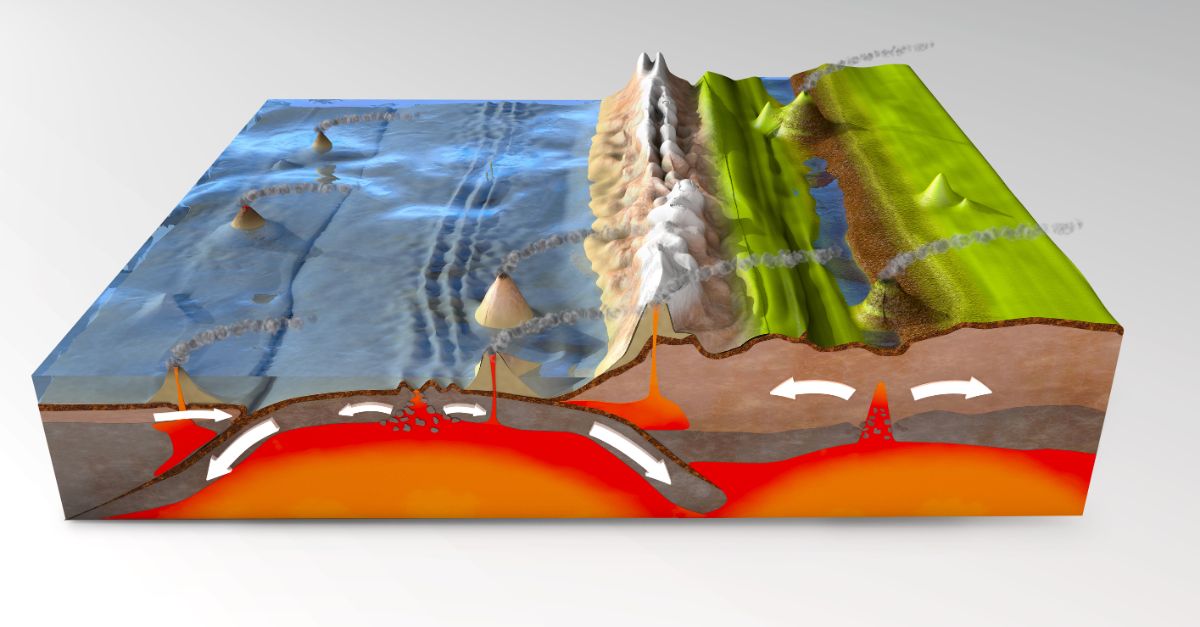

Hayli Gubbi sits in one of Earth’s most geologically active zones. Located in the Danakil Depression within the East African Rift Valley, the volcano rises about 1,640 feet above the surrounding land. Two tectonic plates are actively pulling apart in this region, creating conditions for magma to form and erupt.

The Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program found no record of eruptions during the Holocene period—the past 12,000 years of Earth’s history. Nearby Erta Ale, just 7.5 miles away, maintains an active lava lake, and scientists have monitored it continuously since the 1960s.

Yet Hayli Gubbi remained largely unstudied, forgotten in the world’s volcano monitoring network. This isolation created a blind spot in global volcanic surveillance.

The July Warning Nobody Heeded

Scientists detected something unusual in July 2025. The Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics (COMET) tracked magma movement beneath neighbouring Erta Ale following its July 15 eruption.

Researchers used satellite measurements and identified magma moving southeast from Erta Ale toward Hayli Gubbi. Ground movement of several inches occurred at the summit. Sulphur dioxide emissions appeared. White clouds lingered in the crater. But these signals stayed within scientific databases and academic monitoring systems.

No evacuation alerts were received by pastoralist communities nearby. No public warnings reached Afar residents. The precursor data existed, but the warning system never activated for the public.

12,000 Years: The Holocene Eruption

At 08:30 UTC on November 23, 2025, Hayli Gubbi exploded. Satellite sensors detected the eruption at approximately 11:30 local time. Initial explosions produced a major ash plume rising 33,000–50,000 feet into the air. The eruption enlarged the existing crater and created two entirely new craters at the summit.

People heard ground explosions 31 miles away in Semera, and residents felt a shock wave pass through. This was Hayli Gubbi’s first recorded explosive eruption during the entire Holocene epoch—the geological period spanning 12,000 years since the last Ice Age ended.

Scientists confirmed no prior documented eruptions occurred in this 12-million-year span. The volcano had been geologically quiet for roughly 10,000 years.

Villages Buried in Gray Ash

Within hours of the eruption, ash began covering villages near the Danakil Desert. The community of Afdera, a popular tourist stop for visitors to the Danakil Depression’s geothermal features, became blanketed in volcanic ash.

Hundreds of visitors and local guides found themselves stuck as visibility dropped and conditions worsened. Ahmed Abdela, a resident of the Afar region, described the moment clearly: “It felt like a sudden bomb had been thrown with smoke and ash.” The eruption sounded deafening, with a shock wave that residents felt pass through their bodies.

By November 24, the village remained covered in ash. Tourists planning to explore the Danakil’s colourful mineral deposits found themselves trapped. The eruption had transformed a remote tourism destination into a temporary disaster zone.

Livestock and Livelihoods Threatened

For the Afar pastoralist communities, the eruption posed an existential threat beyond immediate danger. Mohammed Seid, a local administrator, described the economic crisis: “While no human lives and livestock have been lost so far, many villages have been covered in ash, and as a result, their animals have little to eat.”

Fine volcanic particles choked grazing lands. Ash settled into storage tanks and wells, contaminating water sources—a catastrophic problem in an arid region where clean water remains scarce. Livestock, the primary economic resource for these pastoral societies, faced starvation and thirst.

Farmers calculated costs: relocate herds at great expense, purchase supplemental feed in remote markets, or accept losses and sell animals under pressure at low prices.

Aviation Crisis: Airlines Ground Flights

On November 24, India’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) issued an urgent warning. The Toulouse VAAC and Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre had warned of dangerous conditions from the ash plume entering Indian airspace.

The DGCA instructed all airline operators to “strictly avoid” ash-contaminated airspace, change fuel planning and routes, and check volcanic warnings every 30 minutes. Pilots, dispatchers, and cabin crew received orders to report any suspected ash encounters immediately. By dawn on November 25, disruptions appeared in airline schedules.

Air India cancelled 11–13 flights for safety inspections of its aircraft engines. Wide-body jets heading to New York, Newark, Dubai, Doha, and Dammam sat grounded. Akasa Air suspended all India-Gulf flights, cancelling services to Jeddah, Kuwait, and Abu Dhabi scheduled for November 24–25.

Five-State Aviation Lockdown

The ash cloud’s path across India triggered airport safety procedures. The plume entered Indian airspace through Gujarat on the evening of November 24, then drifted northeast through Rajasthan toward Delhi.

By the morning of November 25, airports across at least five distinct Indian states had activated safety measures. Mumbai Airport (Maharashtra) issued passenger warnings. Delhi Airport (Delhi) experienced flight cancellations and delays. Jaipur Airport (Rajasthan) activated runway inspection teams. Ahmedabad Airport (Gujarat) received diverted flights and mandated runway surface checks.

Flight operations were impacted across Punjab’s airspace as the ash cloud continued to drift. The India Meteorological Department tracked the plume at heights of 15,000–45,000 feet, predicting clearance from Indian skies by 19:30 IST on November 25. No official airspace closure occurred, but individual airline caution created a disruption spanning five states.

The Eyjafjallajökull Echo: A 15-Year Lesson Revisited

In April 2010, Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano erupted, with consequences that affected the aviation industry. Over eight days, 104,000 flights got cancelled across Europe—48 percent of expected traffic, with peak cancellations reaching 80 percent on April 18.

Ten million passengers found themselves stranded worldwide. The crisis cost airlines an estimated $200 million per day. Volcanic ash posed a severe threat to jet engines. Fine silica particles can melt inside engines at high altitudes and solidify upon cooling, causing permanent damage and potentially leading to engine failure mid-flight.

In one notable incident, a British Airways B747 flew through ash at 37,000 feet and lost thrust in all four engines. The Hayli Gubbi eruption, though smaller in geographic scope, triggered nearly identical precautions: the same ash-avoidance protocols and engine inspection procedures.

Regulators Scramble: DGCA’s Conservative Response

India’s aviation regulator adopted an extraordinarily cautious approach, reflecting lessons from Eyjafjallajökull and wariness about ash entering jet engines. The DGCA did not issue a blanket airspace closure—that would have created economic chaos across multiple nations’ aviation networks.

Instead, regulators imposed targeted restrictions, including mandatory flight plan reviews, recalculations of fuel, 30-minute monitoring cycles, and engine inspections for aircraft operating near the affected airspace. Airlines facing this warning had to choose between two options: cancelling flights preemptively to avoid engine damage risk or operating with increased monitoring and accepting the liability risk.

Most chose cancellation. Air India’s engineering teams mobilized to conduct engine inspections on multiple aircraft. IndiGo and Akasa Air issued full refunds or rebooking options to affected passengers. A volcano 3,100 miles away was reshaping airline operational schedules.

Scientific Monitoring Gaps Exposed

As investigators examined the eruption afterward, a troubling pattern emerged. COMET had detected magma movement in July 2025. Satellite networks had monitored ground movement. Yet Ethiopia’s volcanic monitoring infrastructure remained underfunded and fragmented.

Research published in “Ethiopian Volcanic Hazards” by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) showed Ethiopia’s seismic monitoring network consists of just 12 instruments spread across the entire country—an impossibly sparse array for a nation containing dozens of active and potentially active volcanoes.

Volcanic eruption identification in remote Ethiopian areas relies “almost entirely on satellite observations and the dissemination of these observations by international researchers to Ethiopian colleagues,” according to the research. Hayli Gubbi’s dormancy meant it received minimal attention. It had no ground seismometers, no local volcano observatory and, it was, effectively, a geological black box to local authorities.

ICAO and VAAC: International Response

The Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), one of nine regional VAACs designated by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), activated its protocol within minutes of detecting the satellite. At 22:57 UTC on November 23, Toulouse issued its first VAAC warning bulletin.

As the ash plume drifted northeast, responsibility transferred to the Tokyo VAAC. Between November 23 and 24, over a dozen warning messages were issued, tracking the plume’s location, altitude, and forecasted path. The ICAO system, formalized following a 1982 incident involving Japan Airlines Flight 9, which flew through volcanic ash and lost all four engines, represents the world’s most sophisticated volcanic-ash warning system.

VAACs coordinate with meteorological offices, air traffic control centers, and airline operations centers. Yet Hayli Gubbi’s eruption revealed a critical gap: the warning system worked perfectly for detecting airborne plumes. But it provided no advance warning to ground communities.

Erta Ale’s Hidden Connection

Geological analysis published after the eruption revealed a striking mechanistic link. Erta Ale’s July 15, 2025, eruption had not been an isolated event. The magma intrusion that powered Erta Ale’s activity did not stop at the volcano’s boundary.

Instead, magma propagated southeast as a dike—a thin sheet of molten rock forcing its way through the crust. Satellite measurements and modelling showed the dike advancing beneath Hayli Gubbi throughout July and August. Ground movement measurements captured several inches of uplift at Hayli Gubbi’s summit.

For four months, this transferred stress accumulated silently beneath the surface. By November 23, the pressure buildup had apparently become critical, triggering an explosive rupture. The eruption represents not a spontaneous reawakening of a dormant volcano, but a cascade event: Erta Ale’s activity triggered a chain reaction 7.5 miles away. This pattern remains well-documented in volcanology but is challenging to predict in real-time.

Monitoring Remote Volcanoes: An Unfinished Agenda

As airlines adjusted schedules and Afar communities assessed livestock losses, a broader institutional question remained unresolved: How should the world monitor volcanoes in remote, sparsely populated regions?

Funding volcanic observatories in developed nations, such as Iceland or the Philippines, proves straightforward—governments protect their own citizens and economic interests. However, establishing ground-based monitoring networks in remote areas such as Ethiopia, Papua New Guinea, or Central Africa requires sustained international coordination and funding mechanisms that remain inadequate.

The Hayli Gubbi eruption will likely prompt increased scrutiny of the Global Volcanism Program’s funding and Ethiopia’s integration into real-time VAAC networks. Regulators in India have flagged the need for mandatory volcanic-ash clauses in airline service agreements and enhanced monitoring of African volcanic zones. Yet without the political will to invest in ground infrastructure, the pattern will repeat.

Sources:

- Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, Hayli Gubbi Volcano Report, 23 November 2025

- NDTV, Ethiopian Volcanic Ash Reaches India; Eyewitnesses Recall Eruption, 24 November 2025

- VisaHQ News, Ethiopian Volcanic Ash Grounds Flights and Triggers DGCA Safety Order Across India, 24-25 November 2025

- Britannica, Hayli Gubbi Ethiopia Volcano Eruption 2025 Ash Plume, 24 November 2025

- BBC News, Ethiopian Volcano Eruption Sends Ash to Delhi Hitting Flight Operations, 25 November 2025

- Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC) Advisory, Hayli Gubbi Eruption Ash Tracking Bulletin, 23-24 November 2025