Beneath the steep walls of Alaska’s Prince William Sound, an unstable mountainside is sending out sharp seismic bursts each autumn and winter. For years, these signals baffled scientists monitoring Barry Arm, a massive landslide above a popular fjord near the town of Whittier. New research now links the strange tremors to water freezing inside bedrock deep below the surface, offering an unexpected tool for tracking one of North America’s most dangerous tsunami threats.

Hidden Landslide Above a Coastal Town

The Barry Arm landslide is enormous—about 500 million cubic meters of rock, roughly the size of a city block and enough material to bury Manhattan under a 200‑foot layer of debris. The slope has been slowly creeping downhill for more than a century, with movement documented in images dating back to at least 1913. It sits roughly 30 miles from Whittier, a community of about 260 people that serves as a gateway for cruise ships and small tour boats entering Prince William Sound.

If this giant mass were to collapse suddenly into the fjord, scientists warn it could generate a towering “megatsunami” at the point of impact, with peak wave heights potentially exceeding 980 feet. Within about 20 minutes, a wave on the order of 30 feet could reach Whittier’s shoreline. The same waters are heavily used by cruise ships, kayakers, and fishing vessels during the tourist season, putting residents and visitors at risk if a major slope failure occurs without warning.

Decoding Mysterious Seismic “Screams”

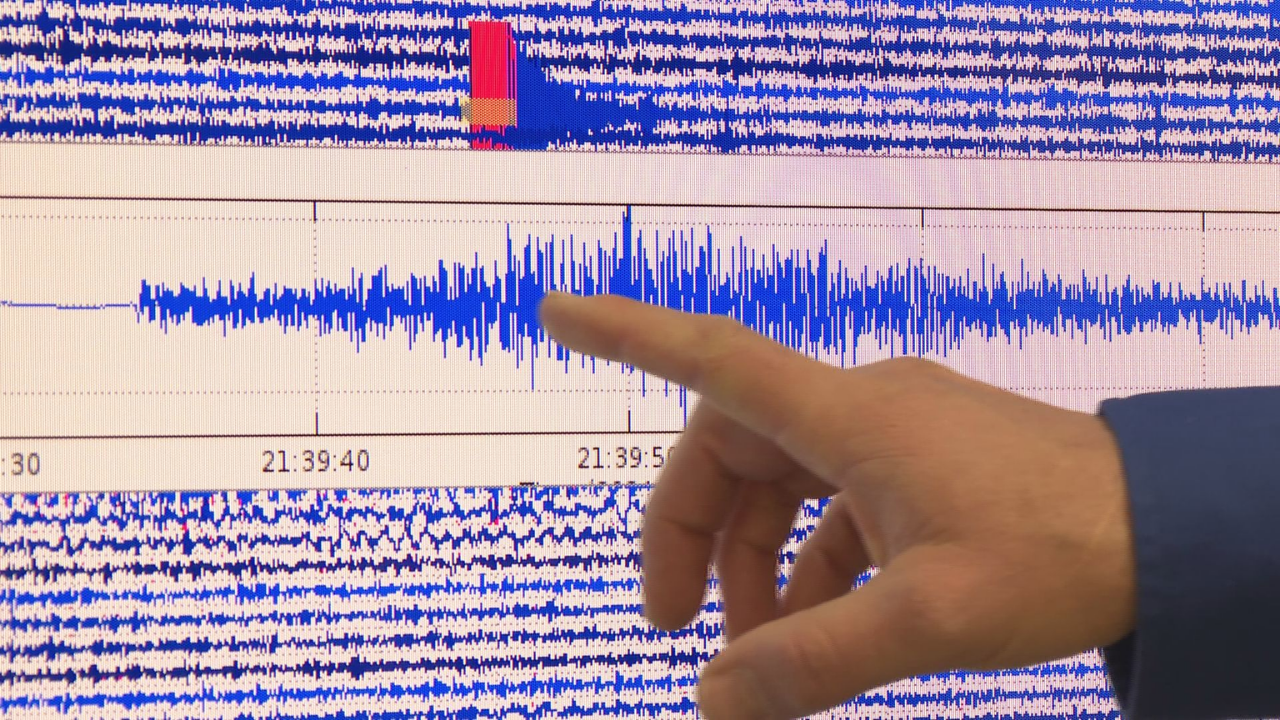

To better understand what is happening inside the mountainside, geophysicist Gabrielle Davy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks spent a year manually examining continuous seismic recordings from Barry Arm. The detailed review, combined with weather records, rainfall data, and ground-based radar that tracks surface motion, revealed a distinct seasonal pattern.

Beginning in late summer, the instruments picked up short, high-frequency seismic pulses that increased steadily from August through December, peaked in mid-winter, and then abruptly stopped in early spring. The pattern repeated reliably year after year. Davy’s team concluded that the signals are caused by freeze–thaw processes beneath the adjacent Cascade Glacier. Water percolates into cracks in the bedrock; as temperatures drop, the water freezes and expands, fracturing the rock in countless tiny brittle events that register as impulsive seismic bursts.

These signals do not directly measure how fast the landslide is moving. However, they act as a window into subsurface hydrology, revealing when and where water is present and under pressure. Because groundwater pressure can act like a hydraulic wedge that weakens rock and reduces friction along potential failure surfaces, tracking these freeze–thaw signatures gives researchers a new way to assess changing conditions inside unstable slopes.

Early Warning From a Record-breaking Tsunami

The potential of seismic monitoring was underscored on August 10, 2025, at Tracy Arm, another fjord in southeast Alaska. There, a 100‑million‑cubic‑meter landslide crashed into the water, generating the world’s second‑tallest recorded megatsunami, with run‑up heights reaching about 1,640 feet on nearby slopes.

In the 18 hours before that collapse, instruments detected roughly 100 small precursor earthquakes coming from the failing slope. Scientists describe this as unprecedented evidence that some large landslides may provide detectable seismic warning in the hours leading up to catastrophic failure. The event has intensified efforts to look for similar patterns in Barry Arm and other high‑risk locations.

To capitalize on these clues, the Alaska Earthquake Center has developed an automated system that continually scans regional seismic data. The algorithm processes three‑minute chunks of recordings every 30 seconds from dozens of monitoring stations. Since August 2023, it has identified 28 landslides across Prince William Sound in close to real time, flagging failures within three to four minutes. That speed is crucial for issuing tsunami alerts to nearby communities and marine traffic.

A Warming Climate and Rising Slope Hazards

New satellite-based studies add to the concern. A 2024 U.S. Geological Survey analysis found 43 landslides in Prince William Sound between 2016 and 2022, with 11 judged capable of producing significant tsunamis. Additional recent events include five successive landslides at Surprise Inlet in September 2024 and a roughly 56‑foot tsunami at Pedersen Lagoon in August 2024.

Many of these hazards are linked to rapid climate warming and glacier loss. Alaska has warmed significantly since 1950, with regional warming of 2.2 to 6.0 degrees Fahrenheit since 1971, faster than any other U.S. state. Barry Glacier, which once buttressed the mountainside above Barry Arm, has retreated dramatically over the past century. As the ice thins and pulls back, it removes the support that helped anchor fractured rock in place, a process scientists call “debuttressing.” Across Alaska’s coasts and fjords, shrinking glaciers are leaving behind steep, oversteepened valley walls primed for paraglacial landslides.

Alaska’s glaciers account for only about 12 percent of global glacier volume but are responsible for roughly 25 percent of worldwide glacier mass loss. They are shedding around 68 billion tons of ice each year. Between 2000 and 2023, average thinning rates nearly doubled, from 36 centimeters a year to 69 centimeters. This acceleration feeds directly into growing landslide and tsunami risks as ice support vanishes, permafrost degrades, and extreme rainfall and temperature swings open new fractures in already weakened rock.

More than 1,000 slow-moving landslides have now been documented across Alaska, some moving just inches per year and others advancing more than ten feet annually. Most are not instrumented, leaving many dangerous slopes effectively invisible to current monitoring networks.

Future of Monitoring and Early Warning

Expanding these networks may be challenging. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration terminated federal funding for nine seismic stations across the state in September 2025, with six in western Alaska, one near Valdez, and two in Southeast Alaska set to go offline. The University of Alaska provided temporary funding to keep them operating through January 2026, reducing the sensitivity of early-warning systems at a time when climate-driven hazards are escalating.

Despite those concerns, interest in seismic precursors is growing. Alaska Earthquake Center scientist Ezgi Karasözen notes that as landslide seismology advances, there is increasing recognition that precursor activity, when it occurs, can provide critical early warning and should be investigated at Barry Arm and similar sites across southern Alaska.

The discovery of seasonal freeze–thaw seismic signals adds a powerful new tool to that effort. By combining these subsurface indicators with surface deformation measurements, rainfall data, glacier retreat records, and automated detection algorithms, scientists are working toward predictive models that could one day flag especially dangerous periods for unstable slopes. In a rapidly warming Alaska, where thousands of potential failures loom above communities and busy waterways, maintaining and improving such monitoring systems may prove essential for reducing risk and saving lives.

Sources:

Seismological Society of America; Searching for Landslide Clues in Seismic Signals from Alaska’s Barry Arm (December 2025)

Phys.org/University of Alaska Fairbanks; Seismic signals research partnership on Barry Arm landslide hazard assessment

U.S. Geological Survey; 2025 Tracy Arm Landslide-Generated Tsunami report and landslide hazards program

Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys; Barry Arm Landslide and Tsunami Hazard documentation

Alaska Earthquake Center; Landslide detection algorithm and Prince William Sound monitoring network data

NASA Landsat; Retreating glacier and landslide threat analysis in Alaskan fjords