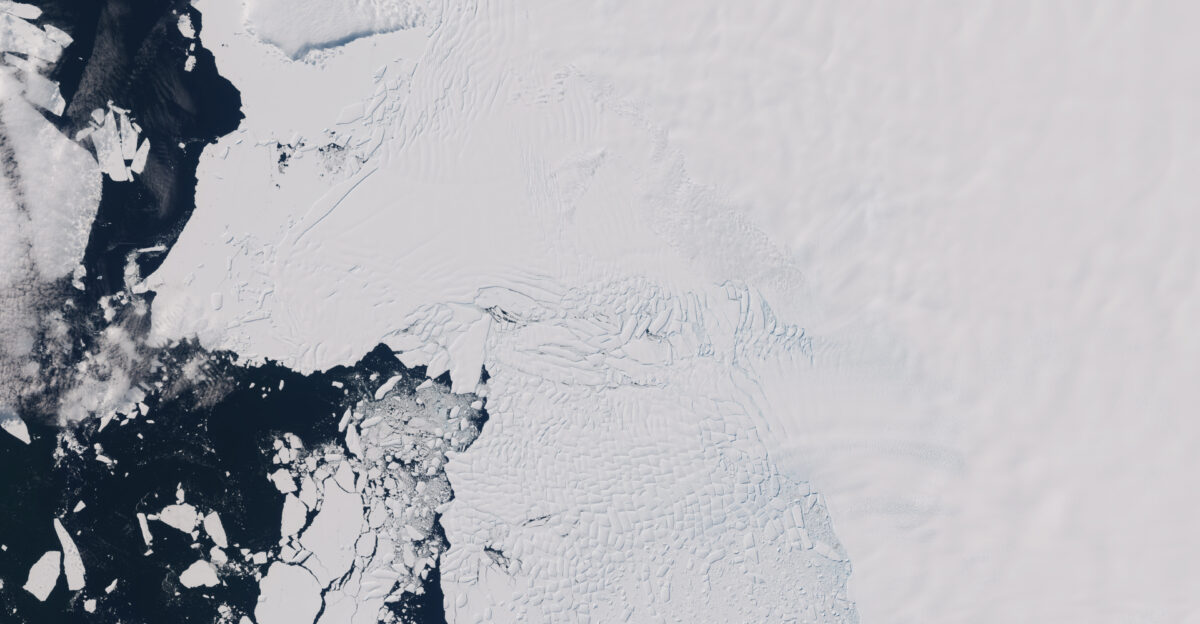

Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier, roughly the size of Florida, has entered a more unstable phase. Scientists are alarmed—this “Doomsday Glacier” is now contributing 4% of global sea-level rise and losing 50 billion tons of ice every year.

If it collapses, it could trigger the failure of the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), causing sea levels to rise by 10 to 11 feet, overwhelming local defenses.

As the glacier accelerates its retreat, the world’s future coastline begins to change before our eyes. How soon will the tipping point come? Keep reading to understand the urgent reality unfolding.

Why Thwaites Is Unraveling

Researchers have linked Thwaites’ deterioration to violent “underwater storms”—swirling vortexes formed where waters of different temperatures collide. These currents travel toward Antarctica and melt the glacier from below.

High-resolution satellite radar data from March to June 2023 reveal warm seawater intruding miles inland beneath the ice, shifting the grounding zone with every tidal cycle and steadily weakening this crucial buttress.

Hidden Tides Beneath the Ice

The new study uncovers a massive “model blind spot”: the grounding zone of Thwaites migrates nearly four miles over a 12-hour tidal cycle. As tides push warm seawater inland, the ice is “jacked up” by centimeters, allowing water to rush in and out.

This daily rhythm increases stress and melt at the base, accelerating the glacier’s retreat in ways current sea-level models do not yet fully factor in.

From Century-Scale Threat to Faster Timelines

Glaciologist Christine Dow notes that scientists once hoped Thwaites would lose most of its ice over 100–500 years, but now fear it could happen “much faster than that.”

Earlier work described the glacier as “hanging on by its fingernails,” and new data suggest that we may be crossing an irreversible tipping point, where small ocean heat changes trigger outsized, unstoppable ice loss.

What Thwaites Holds Back

Thwaites alone could raise global sea levels by over 2 feet if it collapses, but its primary role is acting as a “cork” for the wider West Antarctic Ice Sheet—a basin of ice nearly three times the size of Texas.

If Thwaites fails and that larger system collapses, global sea levels could rise roughly 10–11 feet, transforming coastlines on every continent.

U.S. Coastal Cities in the Crosshairs

Higher seas driven by Antarctic melt would cause catastrophic flooding in major U.S. population centers. Local assessments project that roughly 150–200 million Americans live in coastal counties exposed to this risk.

Cities like New York, Miami, Boston, New Orleans, and San Francisco are facing severe inundation that threatens subways, roads, and energy infrastructure.

Trillions in Property on the Line

Updated estimates suggest that a 10-foot rise puts approximately $1–2 trillion in U.S. coastal property at risk. While earlier analyses by the Union of Concerned Scientists valued 2.5 million at-risk homes at $1.07 trillion.

The inclusion of commercial buildings and critical infrastructure significantly increases total exposure, reshaping long-term investment decisions.

Homeowners, Renters, and Insurance Shakeups

For families in low‑lying neighborhoods, the threat of frequent tidal flooding is already driving up insurance premiums and maintenance costs.

Insurers and mortgage lenders are reassessing risk in regions like Florida and California, which may limit coverage availability or increase borrowing costs, particularly for low-income households with limited relocation options.

Builders, Utilities, and Big Tech Respond

Real‑estate developers and utility companies are beginning to factor Antarctic-driven scenarios into project timelines, acknowledging that current maps may be “dangerously low.”

Some firms are elevating structures or relocating data centers inland, while others are delaying long-lived coastal investments amid uncertainty about exactly when Thwaites will retreat past its tipping point.

Experiments in Geoengineering the Ice

With projections worsening, scientists estimate a 15–to 30-year window to determine whether geoengineering can save the glacier.

Proposals include flexible underwater “curtains” or bubble barriers to block warm deep water and artificial seabed structures to increase drag.

However, critics warn of enormous engineering challenges and ecological risks in the fragile Antarctic environment.

A Glaciologist’s Frontline View

Field researchers describe Thwaites as Antarctica’s most vulnerable glacier. Ironically, it is space-based X-ray radar that has revealed the “invisible” destruction happening miles beneath the ice.

These measurements of ocean heat and stress patterns are critical, as they indicate the glacier is undergoing a “lasting regime shift” that coastal communities must adapt to.

Policy, Politics, and Coastal Planning

Governments are struggling to translate Thwaites‑linked projections into zoning rules. While cities like New York have outlined adaptation strategies through 2100, the discovery of widespread seawater intrusion suggests that current federal and local models may underestimate the speed of sea level rise, complicating the justification for seawalls, wetlands restoration, and managed retreat.

Economic Drag and Inflation Pressures

Rising seas will exacerbate storm-related damages, disrupt ports, and increase infrastructure costs, exacerbating broader economic pressures.

Over decades, the need for repeated rebuilding and protective megaprojects could strain public budgets, influence municipal bond ratings, and filter through to consumers as higher taxes and prices for goods dependent on coastal logistics.

Who Loses, Who Gains—and How to Prepare

Low-lying homeowners and small coastal businesses are most vulnerable, while firms specializing in flood-resilient construction and climate data may see increasing demand.

Consumers are advised to check property‑level flood projections that consider worst-case Antarctic melt scenarios, recognizing that the “dam” holding back West Antarctica is showing signs of failure.

Life After the Doomsday Glacier

Even if a complete Thwaites collapse takes centuries, momentum in the ice sheet means sea-level rise will continue long after emissions peak.

Scientists stress that rapid decarbonization is essential to limit the ultimate pace of change, buying time for cities to adapt before the maps inherited by future generations show major coastal cities as lost territory.

Sources:

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

UC Irvine / PNAS May 2024 Thwaites study

IPCC AR6 Physical Science Basis

CNN / BBC archives

British Antarctic Survey

NOAA Sea Level Rise Technical Report

Union of Concerned Scientists 2018 analysis