New York City’s ageing sewers can only handle 1.75 inches of rain per hour. Hurricane Ida broke that limit in September 2021, dumping over 3 inches in one hour.

The city saw its first-ever flash flood emergency, and eleven people drowned in basement apartments.

But Ida may not be the worst storm possible. City leaders and climate experts now ask: how much worse could it get?

Climate’s Quickening Pace

Climate change is intensifying Atlantic hurricanes. Between 2019 and 2023, about 80% of Atlantic hurricanes got stronger than expected.

Wind speeds increased by 18 miles per hour on average. In 2024, every tropical storm was made stronger by warming oceans.

Some storms gained 10–14 mph extra power. These changes are not small. They turn weak storms into serious threats for cities like New York.

Built on Wetlands

Nearly one million New Yorkers live on land that was once wetlands, marshes, and streams.

The city destroyed 99% of its freshwater wetlands and 86% of its coastal wetlands. Wetlands once absorbed floodwater and filtered storm surge.

Without them, water floods streets, basements, and subway tunnels.

The buildings and sewers were never designed for the intense storms that climate change now creates.

Tightening Squeeze

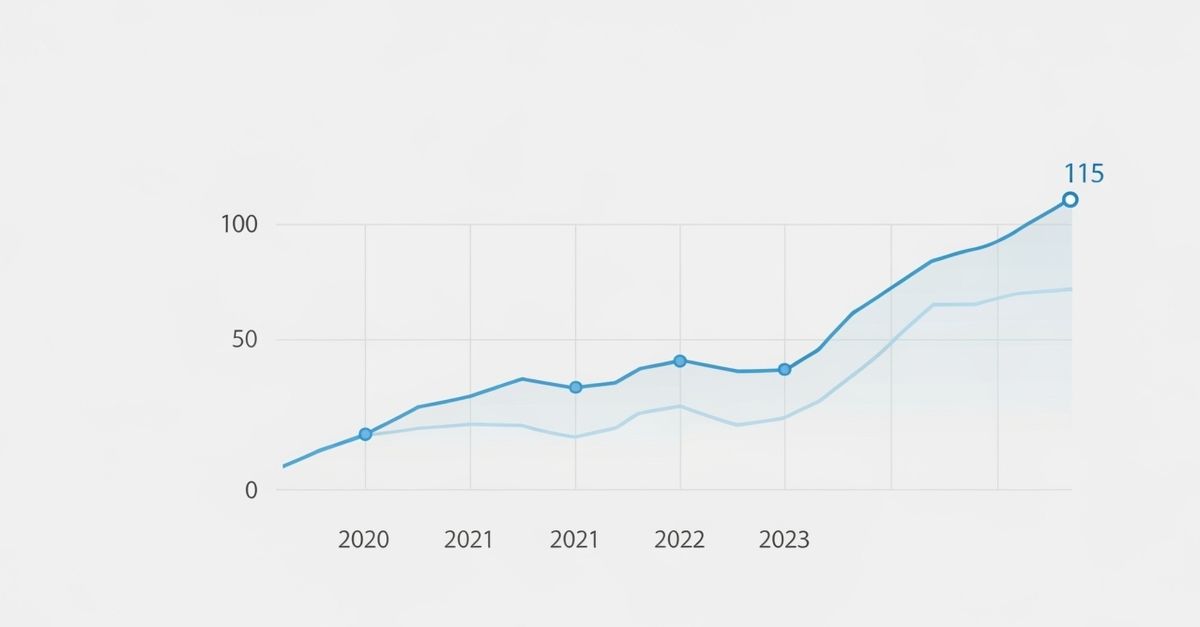

High-tide flooding in New York City has more than doubled since 2000. It now happens 10–15 times per year in lower Manhattan.

Sea levels have risen by over one foot since 1900 and are projected to rise by another 14–19 inches by the 2050s. Heavy rain is becoming more intense.

The share of rainfall from extreme storms is expected to increase from 41% to 47% by mid-century. These problems feed each other.

The Superstorm Model

First Street Foundation released a new model in November 2025. It shows what a worst-case hurricane could do to New York City.

Picture this: a Category 1 hurricane hits New Jersey at high tide. It brings 4 inches of rain per hour and a 16-foot storm surge.

This would flood 25% of the city and trap over 2 million people in Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Queens. Damage could exceed $20 billion.

Borough Unequal

Flooding would not affect all areas equally. Manhattan and the Bronx would face major damage, but Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Queens would suffer most.

Over 80% of floodwater would impact these outer boroughs, where drainage systems already fail.

Coney Island could sink under many feet of water. Kissena Park in Queens could see 19 feet of water. The Cross Bronx Expressway underpasses could be submerged under 47 feet of water.

Basement Tombs

Hurricane Ida killed eleven people in basement apartments in September 2021. They lived in cheap housing—the only homes poor immigrants could afford.

A study showed that victims could not escape due to blocked exits and rapidly rising water. One man tried to save his dog and never returned.

In October 2025, two more men died in basements during a smaller storm. A 19-foot flood would render basements inaccessible.

The Subway Vulnerability

The MTA runs 13 of 24 subway yards that flood easily during storms. This is the city’s biggest flood risk. Hurricane Ida flooded 45 subway stations, shut down 11 lines, and resulted in millions of dollars in cleanup costs.

The problem: subway drains connect to city sewers. When heavy rain fills the sewers, water backs up into tunnels faster than pumps can drain it. Today, only 6% of the city’s 472 stations have protection.

The Century Becomes a Decade

First Street says this Category 1 hurricane scenario might happen once every 100 years today.

But Dr Jeremy Porter, who leads First Street’s climate work, warns: “It will become increasingly common with the evolving climate.” His models show warming oceans, shifting wind patterns, and more moisture in the air.

Climate experts say the number of major hurricanes (Category 3 and above) has doubled since 1980. A rare event could become routine in 20 years.

The Cascade Collapse

A superstorm would break more than just buildings. Salt water would corrode electrical stations, cutting power for weeks. Water treatment plants would fail, making drinking water unsafe.

The Port Authority would stop moving goods to the Northeast. Hospitals would evacuate patients during emergencies. Most importantly, the sewer system would need $30 billion and 30 years to be fully fixed.

The city now spends $1 billion per year on sewers. At that rate, upgrades will be finished by 2055. Three more decades of risk.

The Frustration Deepens

Hamilton Beach in Queens floods at nearly every high tide—about once a month. Salt water fills streets, basements, and sewers that back up into homes.

Residents move cars to higher ground before storms. Some places put sandbags by doors in August, before heavy rain even starts.

One resident said, “We fear every day that it will happen again. Just imagine the devastation a direct hit would bring.” For them, official warnings feel useless.

Defensive Measures Begin

The MTA is spending $700 million over five years to protect subways. They’re raising station entrances, upgrading 250 pump stations, and reinforcing walls.

The city has protected 28 stations—only 6% of all 472 stations. Mayor Adams announced a $390 million plan for Brooklyn’s Bushwick neighbourhood.

It will replace three miles of old sewers and boost drain capacity by 850% in that zone.

The city is also adding green spaces that absorb water. But the effort is tiny compared to the need.

The Funding Chasm

New York spends approximately $1 billion annually on sewers and storm drains. Full upgrades would cost $30 billion.

At this pace, work finishes in 2055. The federal government only covers 20% of the MTA’s budget.

The state and city must pay the remainder, but property taxes are declining because climate risks are lowering real estate values.

First Street estimates that U.S. property values could decline by $1.23 trillion by 2055 due to climate-related damage. Cities face an impossible choice: spend billions they don’t have or accept the risk.

Expert Doubt

NYC’s environmental chief, Commissioner Rohit Aggarwala, said bluntly: “We have an infrastructure that was designed for an environment we no longer live in.

It’s as if New York City moved 500 miles south.” The federal government reclassified New York’s climate in 2020, from coastal temperate to subtropical.

When asked if the city can adapt in time, Aggarwala said: “It remains unclear what strategies could work.”

Some experts now suggest buying out flood-prone homes and relocating the residents. But politics make this nearly impossible.

The Question Ahead

At what point does protecting a city become impossible? New York survived Superstorm Sandy in 2012, which caused $38 billion in damage.

The city rebuilt. But the next superstorm would cost twice as much. It arrives when the environment keeps changing, and sewers won’t be fixed for decades.

First Street’s model shows that 25% of the city will be underwater, 2 million people will be at risk, and 47 feet of water will be under a highway.

The real question: Will the city take radical action, or accept disaster as normal?

Sources:

New York Times, November 25, 2025

First Street Foundation Climate Risk Assessment, 2024

AM NY, July 22, 2025

Real Estate Climate Impact Report, 2025

ENR, July 21, 2025

Smart Water Magazine, March 2, 2025