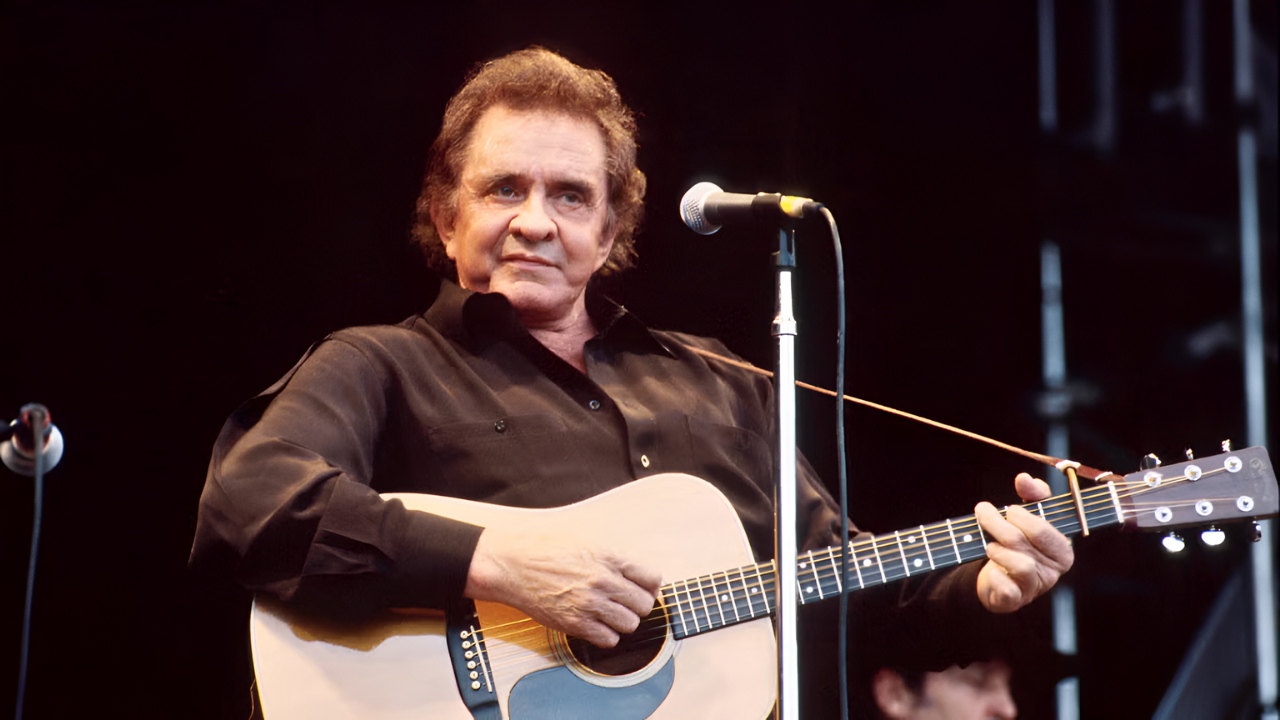

A courtroom confrontation over a Coca-Cola college football commercial has triggered the first major legal battle under Tennessee’s 2024 ELVIS Act, a groundbreaking statute designed to protect artists’ voices, likenesses, and images even after death. The John R. Cash Revocable Trust alleges that Coca-Cola aired a national advertisement using a soundalike performance of Johnny Cash’s distinctive baritone without permission or licensing, setting the stage for a case with far-reaching implications for advertising, artificial intelligence, and posthumous rights protection.

The commercial, which aired during college football broadcasts beginning in August 2025, featured tribute performer Shawn Barker delivering vocals styled unmistakably after Cash’s iconic sound. According to the estate’s legal filing, Coca-Cola never sought permission despite knowing that voice rights are protected under Tennessee law. Attorney Tim Warnock of Loeb & Loeb characterized the alleged violation as fundamental identity theft, stating that using an artist’s voice without consent constitutes theft of integrity, identity, and humanity.

The ELVIS Act’s Moment of Truth

Tennessee’s ELVIS Act emerged from growing concerns about voice cloning and impersonation in the digital age, particularly following viral incidents like the unauthorized “Fake Drake” song in 2023. The statute closes a legal gap by explicitly protecting artists’ voices as intellectual property, extending protections decades beyond death. This case represents the law’s first significant courtroom test, giving it nationwide legal significance and potentially shaping how similar disputes are resolved across the country.

The Cash estate is seeking a court injunction to remove the advertisement and financial damages for voice-rights infringement. The outcome will establish precedent for how soundalike recordings are treated in commercial contexts and whether tribute performances cross into legally actionable territory when used in advertising.

A Commercial Reaches Millions

College football broadcasts command enormous audiences, with national campaigns aired over multiple months potentially reaching 50 to 100 million viewers based on typical seasonal viewership. That scale amplifies both the commercial benefit Coca-Cola allegedly gained and the legal stakes of the case. The broader the exposure, the greater the potential damages and the more significant the precedent.

The lawsuit arrives amid heightened scrutiny of Coca-Cola’s promotional practices, amplifying reputational risk at a moment when authenticity in advertising resonates with consumers more than ever. Being accused of appropriating the voice of a beloved American cultural icon could damage the brand far beyond legal penalties, as millions of viewers may have unknowingly heard what the estate views as an unauthorized imitation.

Echoes of Midler v. Ford

This case revives legal foundations established nearly four decades ago. In Midler v. Ford (1988), Bette Midler won a landmark judgment after Ford Motor Company used a soundalike when she refused to license her voice. The court ruled that a famous voice receives the same legal protection as a face or name, and commercially imitating it constitutes appropriation. Now, the Cash estate applies that precedent in a new era where voice law intersects with artificial intelligence and modern publicity-rights statutes.

The parallel is striking: both cases involve major corporations attempting to leverage instantly recognizable voices without authorization. The difference is that modern law now explicitly codifies voice protection, whereas Midler relied on broader publicity-rights doctrine.

Industry-Wide Implications

Advertising agencies and brands that once viewed soundalikes as cost-saving shortcuts now face direct legal exposure. Agencies share liability when campaigns involve unauthorized likeness use, placing creative firms directly in the legal crosshairs alongside their clients. The case signals that the industry’s approach to voice licensing must fundamentally shift.

Since Johnny Cash’s death in 2003, his estate has authorized only select uses of his recorded work, including major Super Bowl broadcasts. His voice remains a controlled, high-value cultural asset protected commercially like his songs and recordings. If Coca-Cola deliberately used a soundalike to bypass licensing approval steps while leveraging Cash’s instantly recognizable sound, it suggests a calculated strategy to profit from his legacy without compensating it.

Estates as Active Protectors

Across entertainment industries, estates are defending posthumous rights more aggressively than ever. Laws in over 20 states now protect publicity rights for decades after an artist’s death, transforming voices, likenesses, and personas into valuable long-term intellectual property. Johnny Cash died 22 years ago, yet his voice can still trigger litigation—proof that legacy protection doesn’t end when the artist does.

Broader Implications for AI and Beyond

While this case stems from human mimicry rather than artificial intelligence, its implications extend into the rapidly expanding AI-voice landscape. Modern voice-cloning models can convincingly replicate vocals from minutes of audio. Music streaming platforms are already tightening rules to combat vocal replication without consent. If a soundalike performance without permission proves actionable in court, AI-generated voice cloning could face even steeper liability.

Ironically, the ELVIS Act was drafted in response to AI voice synthesis, yet this case demonstrates that the threat of unauthorized voice use existed long before machine-generated mimicry. A law created for deepfakes applies equally to traditional impersonation, proving the vulnerability predates modern technology.

Tennessee’s National Leadership

Tennessee has positioned itself as the epicenter of voice-rights law. Industry groups including the RIAA, SAG-AFTRA, and the Recording Academy all backed the ELVIS Act, signaling coordinated momentum toward stricter artist-likeness protection. If the Cash estate prevails, similar legislation could ripple nationwide, potentially influencing federal proposals like the NO FAKES Act.

The outcome of this case will determine whether a voice can be owned, controlled, and protected as intellectual property long after an artist’s death—and whether imitation, in the commercial context, constitutes infringement. One courtroom decision could reshape how the entertainment industry, advertising sector, and technology companies approach voice licensing and consent for decades to come.

Sources:

Johnny Cash Estate v. Coca-Cola Company, Case No.3:25-cv-01373 (U.S. District Court, Middle District of Tennessee, November 25, 2025); Legal filing documents and complaint

Tennessee General Assembly, Ensuring Likeness, Voice, and Image Security (ELVIS) Act of 2024, codified at Tenn. Code Ann. § 47-25-1105 et seq. (signed into law March 21, 2024; effective July 1, 2024)

Bette Midler v. Ford Motor Co., 849 F.2d 460 (9th Cir. 1988); U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit opinion

Rolling Stone, Independent, and Complete Music Update coverage of the Cash estate lawsuit (November 2025); Published reporting on commercial details, damages sought, and ELVIS Act implications