During 2020 construction for Stanley’s new Tussac House, crews digging 6 m down hit a peat layer full of intact tree trunks and branches. At first glance, the wood looked like driftwood, notable on an island treeless for millennia.

Researchers realized the logs were unbelievably old. “These were so well preserved, they looked like they’d been buried the day before, but they were in fact extremely old,” said Dr. Zoë Thomas of the University of Southampton.

The find stunned everyone and raised urgent questions about the Falklands’ hidden ancient past.

Impossible Find

The Falkland Islands’ climate is famously forbidding. Boisterous westerly gales, nutrient-poor peat soil and acid pH keep plants low – today, only tussac grass (up to ~3 m tall) and shrubs cover the land.

Trees simply can’t grow in such conditions. So finding ancient trunks in a Stanley peat bog was astonishing.

Earth.com noted that “no one knew how long they had been buried… but living trees have been missing from the islands for at least 40,000 years”. The contradiction demanded urgent investigation.

South Atlantic Puzzle

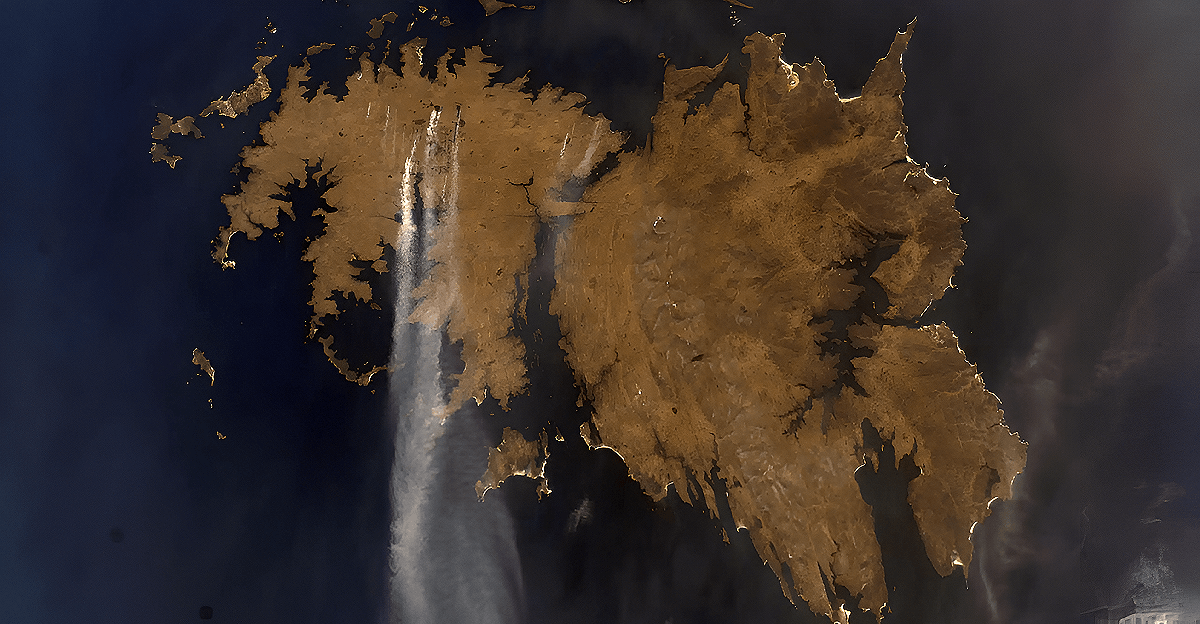

The Falklands lie at ~52°S, about 540 km east of mainland South America, on a fragment of old oceanic crust from Gondwana’s breakup.

The modern climate is cold and windy – mean annual temperature ~5.5°C, with westerly winds averaging ~8.5 m/s and ~600 mm rain per year.

Despite being only ~8° north of the southern tree line, the islands have no native trees: vegetation is limited to acid grasslands, hardy shrubs and coastal tussac grass.

The sight of fossil logs in this austere landscape deepens the mystery.

Climate Clues

About 34 million years ago, Earth plunged into the Oligocene Ice Age with Antarctica’s ice sheets expanding dramatically – yet mid-latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere stayed surprisingly warm.

Scientists call this the “enigmatic Oligocene.” Proxy sea-temperature records and models indicate that these high-latitude oceans were warmer than expected given low CO₂.

As one study found, Oligocene warmth “belies a simple relationship between climate and atmospheric CO₂”.

This implies that ocean circulation and other feedback played a key role in keeping regions like the Falklands comparatively mild.

Ancient Forest Revealed

Lab analysis showed the peat held a temperate rainforest of southern beech (Nothofagus) and podocarps.

Dating of its pollen and spores places this forest at roughly 15–30 million years ago. It’s only the Falklands’ second known fossil forest – the first (on West Point Island) proved to be younger (late Miocene).

Dr. Zoë Thomas recalled, “we were quite intrigued… but nothing prepared us for what we saw when we travelled to the site”. The revelation overturned assumptions and gave scientists a vivid window into a lost ecosystem.

Regional Impact

The fossils indicate a cool, temperate rainforest – scientists found evidence of Podocarpaceae, Nothofagaceae (southern beeches) and even Myrtaceae species.

Many of these plants are now extinct; their closest living relatives are in southern South America, New Zealand and Tasmania.

Such forests still cover parts of Patagonia’s Tierra del Fuego today.

Prevailing westerly winds would have spread seeds across the ocean, so in the late Oligocene–early Miocene the Falklands likely served as stepping stones between forests of Patagonia and Antarctic lands.

Community Discovery

Thomas heard about the find through local word-of-mouth. Working on a different project in Stanley, she was told that a builder had dug up something unusual at the Tussac House site.

She and colleagues – including scientists from the South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI) – went to inspect the excavation.

“We were in the Falklands carrying out research for a different project when a fellow researcher… mentioned they’d heard something interesting had been dug up by a builder”.

On reaching the pit they found the pristinely preserved tree trunks awaiting study.

Scientific Methods

Scientists combined field and lab techniques to date the find. Peat cores and wood fragments were sent to the University of New South Wales, where powerful electron microscopes examined the cellular structure.

Radiocarbon dating was impossible (the wood is too old), so researchers instead turned to fossil pollen and spores in the peat.

By comparing these microfossils to well-dated global records, the team pinned the forest’s age at roughly 15–30 million years.

These modern microscopy and palynology methods provided the only viable way to date such ancient plant material.

Global Context

Nothofagus (southern beech) has an 80-million-year Gondwanan fossil history, but molecular clocks reveal that many of its island populations arrived by oceanic dispersal.

For example, researchers showed that some Nothofagus connections (like Australia–New Zealand) “can only be explained by long-distance dispersal”.

The Falklands forest fits this pattern, demonstrating yet another instance of seeds and spores traveling by wind or birds. In warm epochs, such jumps linked forests across the Southern Hemisphere, complementing and complicating the simple vicariance story.

Second Discovery

In fact, Tussac House’s forest is only the Falklands’ second ever found. The first, on West Point Island (1899), was later dated to the mid Miocene–early Pliocene.

By comparison, the Tussac bed is older (Late Oligocene–Early Miocene).

Reflecting on the luck involved, Dr. Thomas said the find required “a range of lucky coincidences” – “there may well be other deposits of this nature but it would be pot-luck to try to find them”.

These rare discoveries show how exceptional the hidden fossil forests are.

Climate Transformation

By the late Miocene (around 15–20 Ma), the rainforest had vanished. Researchers agree the climate shifted to colder, drier conditions – the most likely driver of the forest’s demise.

Expanding Antarctic ice and changing wind patterns blanketed the islands in cold storms.

A global cooling trend after the Miocene Climatic Optimum led to reduced rainfall and ice-age conditions in the Southern Hemisphere.

As temperatures fell and winds strengthened, the lush highland woods gradually converted into peat bogs and grassland, leaving the Falklands treeless.

Construction Timeline

The fossil find was incidental to a major local project. Excavation for Tussac House – a new assisted-living complex in Stanley – began in 2020. The construction contract (worth £11.675 million) was awarded to RSK Falklands Ltd.

By early January 2025, the building was complete, containing 32 extra-care apartments.

Just days later residents were moving in, unaware that, beneath the new floor, they had unearthed a well-preserved patch of Falklands prehistory.

Preservation Success

The waterlogged peat acted like a time capsule for the wood. The logs were so intact that researchers at first thought they were modern driftwood. “The tree remains were so pristinely preserved they looked like driftwood,” Dr. Thomas recalled. In the lab,

Scientists trimmed micron-thick slices from the wood and imaged them with an electron microscope.

This remarkable preservation means even cell anatomy can be examined; for example, the wood’s cell patterns revealed podocarp traits matching the pollen evidence.

Research Challenges

Ironically, today’s Falklands climate remains inhospitable to forests. Winds average ~8.5 m/s and bitter maritime cold (mean ~5.5°C) plus acidic, nutrient-poor peat soils form a near-perfect barrier to young trees.

Current projections suggest the region will warm a bit but also become drier.

Even future climate scenarios offer no easy path back to woodlands: the islands’ exposure and soil chemistry make natural forest recovery extremely unlikely.

Future Implications

The discovery raises the exciting possibility that other treeless subantarctic islands may conceal ancient buried forests. Each such find is a paleoclimate archive: its fossils and geochemistry encode past weather and ocean conditions.

For instance, isotopes from the peat could reveal ancient rainfall or winds.

As researchers note, every new record “adds to our current knowledge of the role of climate change and transoceanic dispersal in shaping high-latitude ecosystems in the Southern Hemisphere”.

Such archives help scientists refine models of Antarctic ice behavior by linking past warm climates to ocean patterns.

Policy Connections

These findings have lessons for climate science. The Oligocene world – with Antarctic ice yet mild southern oceans – shows that simple CO₂ rules can’t predict everything.

Fossil forests like Tussac House provide real data to calibrate models: if simulations can reproduce that ancient forest under low greenhouse gases, confidence grows in their forecasts.

Paleo-archives help refine projections of Antarctic ice response by constraining feedback and circulation. Understanding these deep-time climates is crucial for improving future climate projections and policy.

International Significance

This finding adds a key piece to the puzzle of Southern Hemisphere biogeography. It provides fossil proof that many island plant communities once arrived “via transoceanic dispersal by wind, ocean currents and birds” during warm periods.

This fits molecular studies showing Gondwanan plants often hopped across oceans.

The work was itself a global collaboration (including scientists from the Falklands, UK, Australia and beyond), demonstrating how shared natural heritage can unite researchers worldwide.

For example, the results have been published in Antarctic Science and discussed by teams around the globe.

Environmental Legacy

The Falklands’ shift from rainforest to grassland mirrors a broad Southern Hemisphere cooling trend. As temperatures fell, Gondwanan forests fragmented and podocarp conifers retreated to refugia.

Today’s surviving southern beeches and podocarps – like Fitzroya and Podocarpus in southern Chile, or kauri and rimu in New Zealand – are descendants of those ancient woods.

Their modern patchy ranges reflect where forests held on through ice ages. Conservation efforts now protect these relict species and their critical habitats in Chile and New Zealand.

Cultural Impact

The discovery resonates beyond science. For Falkland Islanders, it adds a chapter to their landscape’s story – a link to a long-buried rainforest once beneath their feet.

This deep environmental history can enrich local identity and education. Schools and museums may highlight the ancient forest to show how dramatically the world can change.

There is even potential for new tourism: visitors already come for wildlife, and some paleontology enthusiasts or curious travelers might visit the islands to learn about this lost forest, perhaps through exhibits or guided talks.

Broader Reflection

The Tussac House find underscores science’s dependence on chance and community. As Thomas notes, “no one had any idea that six meters under their feet were perfectly preserved relics of an ancient rainforest”.

It was only because a local mentioned the discovery that researchers arrived in time. This serendipity teaches us that today’s treeless moors are mere snapshots – the windswept Falklands were once lush woods.

Each such fossil find revolutionizes our view of Earth’s dynamic history, highlighting how local engagement can unlock hidden chapters of the planet’s past.