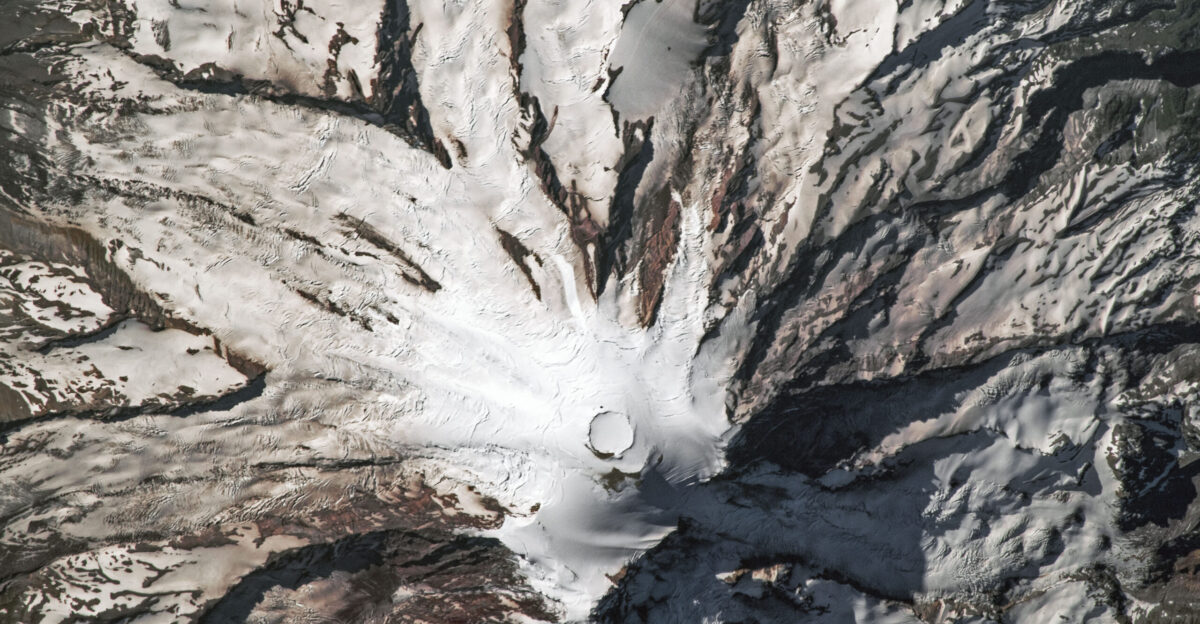

The highest point in the continental United States just moved. Columbia Crest, the iconic ice dome that has crowned Mount Rainier for generations and guided countless climbers to victory, has melted away completely. In its place stands an unglamorous rocky outcrop on the southwest crater rim—a bare stone summit where frozen majesty once reigned. The discovery, documented in a peer-reviewed study published in November 2025 in Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, reveals that America’s most glaciated peak is collapsing faster than anyone anticipated.

The Mountain Transformed Overnight

The transformation wasn’t gradual or subtle. Columbia Crest has descended more than 20 feet since the mid-20th century, according to research from Seattle University and Utah State University. The new summit, located roughly 400 feet from the traditional high point, now stands taller than the melting ice that preceded it. Climbers who reach what they believe is the top will discover they’ve arrived at the wrong place—a disorienting reality for those who trained for years to plant flags on what they thought was America’s highest point.

Lead researcher Eric Gilbertson, a mechanical engineering professor at Seattle University, assembled a team and hauled 30 pounds of precision GPS equipment across 18 miles of crevasse-crossed glaciers to reach the summit in late August 2024. The expedition crossed ladders over gaping holes in the ice and navigated avalanche zones to obtain measurements that told a stark story: the mountain was melting faster than anyone had imagined. Gilbertson had attempted the same survey in September 2023 but was forced to turn back miles from the summit. “The mountain was too melted out,” he explained. “Too many crevasses opened up.” A researcher trained to handle alpine conditions was stopped by deteriorating terrain—a single failure that speaks volumes about the speed of collapse.

A Crisis Spreading Across Washington’s Peaks

Mount Rainier isn’t alone. The continental United States has only five ice-capped summits, and all five are in Washington State. Four of them have now lost 20 feet or more of elevation. Of these five peaks, only Liberty Cap and Colfax Peak still maintain year-round ice at their highest points. Eldorado Peak, East Fury, and Mount Rainier have all watched their rocky cores emerge as the ice that buried them for millennia vanished.

The acceleration is undeniable. National Park Service data from 2023 showed that Mount Rainier has lost roughly 50 percent of its glacier mass since 1896—but the most significant changes happened in the last 30 years. Three glaciers—Stevens, Pyramid, and Van Trump—are effectively gone or in terminal decline. What took generations to begin now races at breakneck speed.

Why the Ice Is Disappearing

Summit temperatures have risen nearly 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1950s, a dramatic warming at elevations where cold was supposed to be permanent. The mechanism is deceptively simple: more precipitation at summit elevations now arrives as rain rather than snow, preventing the accumulation that would rebuild ice. Rain at 14,000 feet was once unthinkable. Now it’s routine. The summits lose ice constantly and gain almost nothing to replace it.

Scott Hotaling, a watershed sciences professor at Utah State University and co-author of the study, worked as a climbing ranger on Mount Rainier. His reaction to the findings revealed how unexpected this was: “I was shocked… Because Mount Rainier is the highest, coldest mountain in the Western U.S., and climate change has such a dramatic impact, year over year, at the summit—that means it’s happening everywhere.”

Consequences for Millions Downstream

This isn’t abstract science. Mount Rainier’s glaciers are the headwaters of five major Pacific Northwest rivers—water systems that provide drinking water to millions, spawning grounds for iconic salmon runs, and power for hydroelectric dams. Every foot of ice lost is a foot of summer water supply diminished. Downstream communities, cities, and ecosystems all depend on Rainier’s frozen reserve.

Roughly 10,000 adventurers attempt Mount Rainier’s summit annually, with about half succeeding. Many dream about it for years, training and saving money to chase a mountaintop experience that their parents had. But the route is becoming more dangerous. The terrain is more exposed. The crevasses are deeper and more unpredictable. The mountain they’re climbing is becoming a different mountain.

What Comes Next

Mount Rainier National Park has not confirmed the study’s findings. Terry Wildy, the park’s chief of interpretation, stated the results are “not confirmed” and raised concerns about methodology. The National Park Service requested raw data for independent verification. In 2026, the Land Surveyors’ Association of Washington plans its own expedition to verify the measurements.

However, what makes this wait unbearable is that by the time surveyors return to Rainier in 2026, more ice will have melted. More crevasses will have opened. The summit may have shifted further. The mountain won’t wait for institutional verification. It will continue to change, melt, and become something new. If Mount Rainier—America’s most heavily iced peak, sitting at 14,000 feet in one of the coldest regions of the contiguous U.S.—cannot escape warming, then no mountain can. There are no refuges left. The consequences are visible now, not in distant futures but in the ice melting under our feet and in the summits shifting. The top of Washington State just moved. And in moving, it’s rewriting the future of the Pacific Northwest.

Sources

Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research (November 2025) — Gilbertson et al., peer-reviewed study on Mount Rainier elevation loss and ice-capped peak shrinkage

Seattle University & Utah State University Research Team — Lead investigators Eric Gilbertson and Scott Hotaling; differential GPS survey data (August 2024)

National Park Service Mount Rainier Glacier Monitoring Program — Historical glacier mass balance and elevation data (1896–2023)

U.S. Geological Survey Climate & Cryosphere Research — Regional temperature trends and precipitation pattern documentation

Land Surveyors’ Association of Washington — Independent verification expedition planned 2026