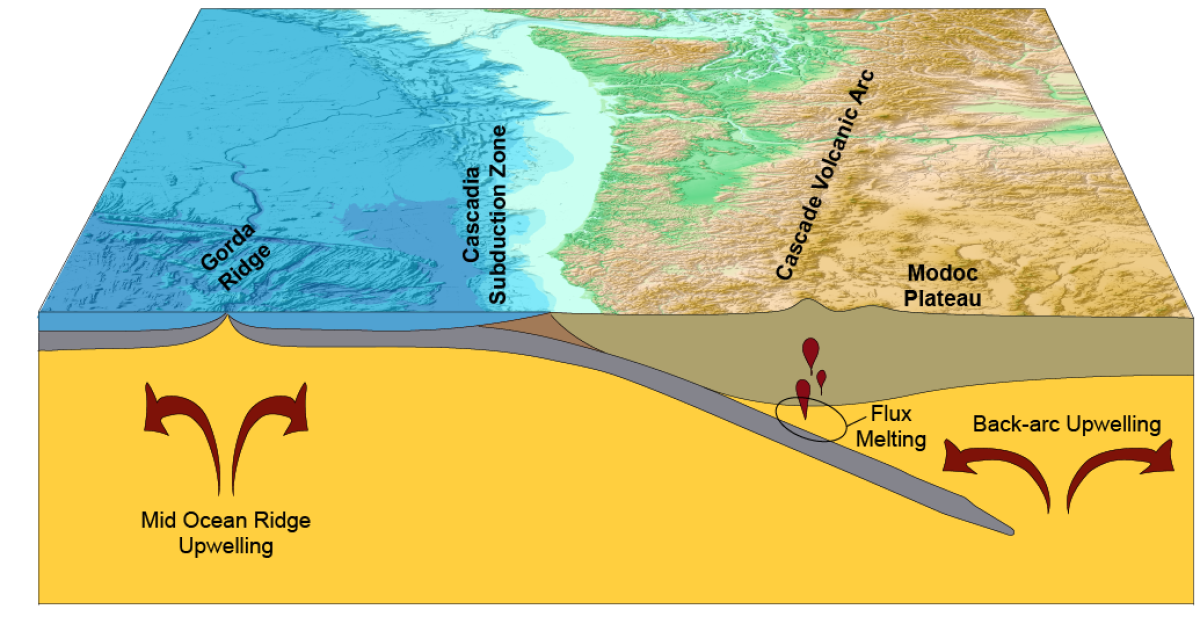

A massive earthquake off the Pacific Northwest coast is not a distant abstraction but a well-defined geological threat. Along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, where one tectonic plate dives beneath another, scientists say the eventual rupture will drop parts of the shoreline by as much as six feet and generate a tsunami that could tower up to 100 feet. FEMA projects approximately 13,000 deaths and $134 billion in total economic losses from this event.

Silent shifts deep underground

Far below the region’s coastal cities, the fault does not always move in sudden jolts. Roughly every 14 months, the plates slide past each other in what scientists call slow-slip events, gradual motions that unfold over weeks instead of seconds. These events are almost imperceptible at the surface and can only be detected by high-precision GPS instruments that record millimeters of movement.

Studies of other subduction zones, including the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, have linked such slow-slip episodes to later major quakes, suggesting they may be part of a buildup process. In Cascadia, the picture is complicated by the presence of multiple slow-slip zones. In 2013, researchers observed that when two of these zones merged, the rate of slip increased eightfold, indicating that fault movement can accelerate abruptly once different slipping fronts interact.

This heightened motion is interpreted as a sign that stress is redistributing along the plate boundary. Scientists are monitoring these cycles closely to determine whether particular patterns in slow slip could mark the approach of a full-margin rupture.

Hidden tremors and deep signals

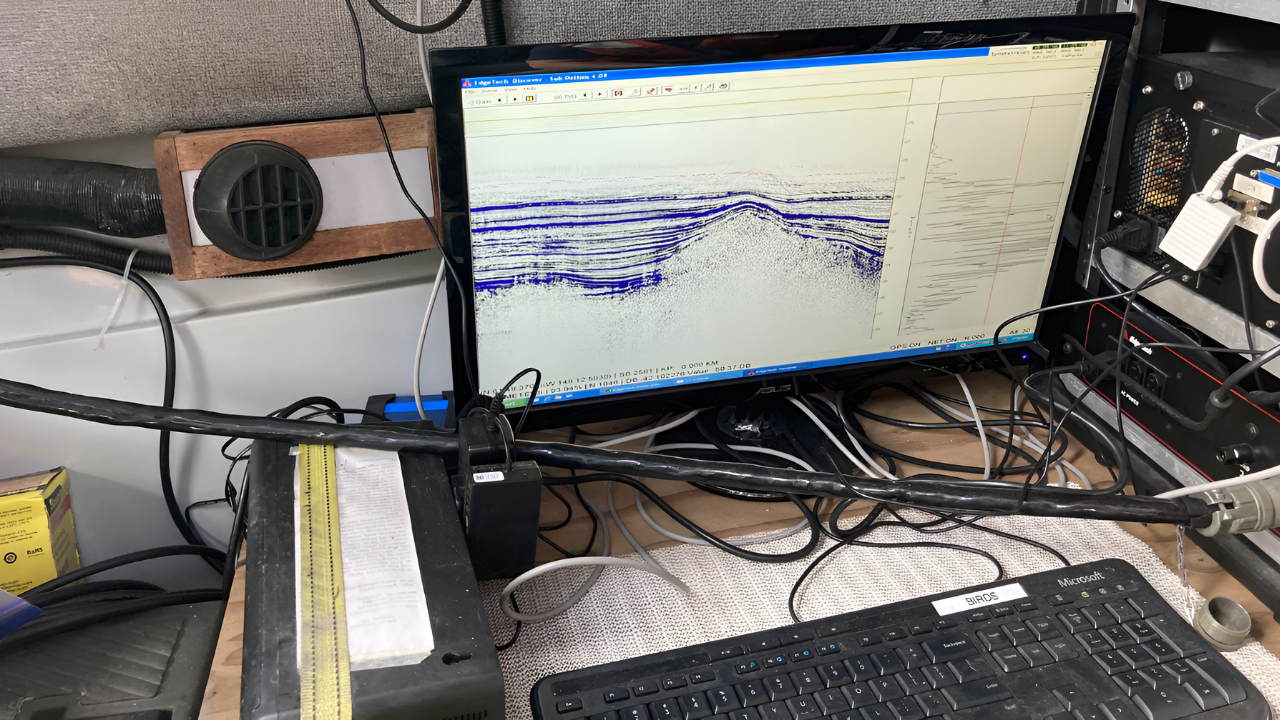

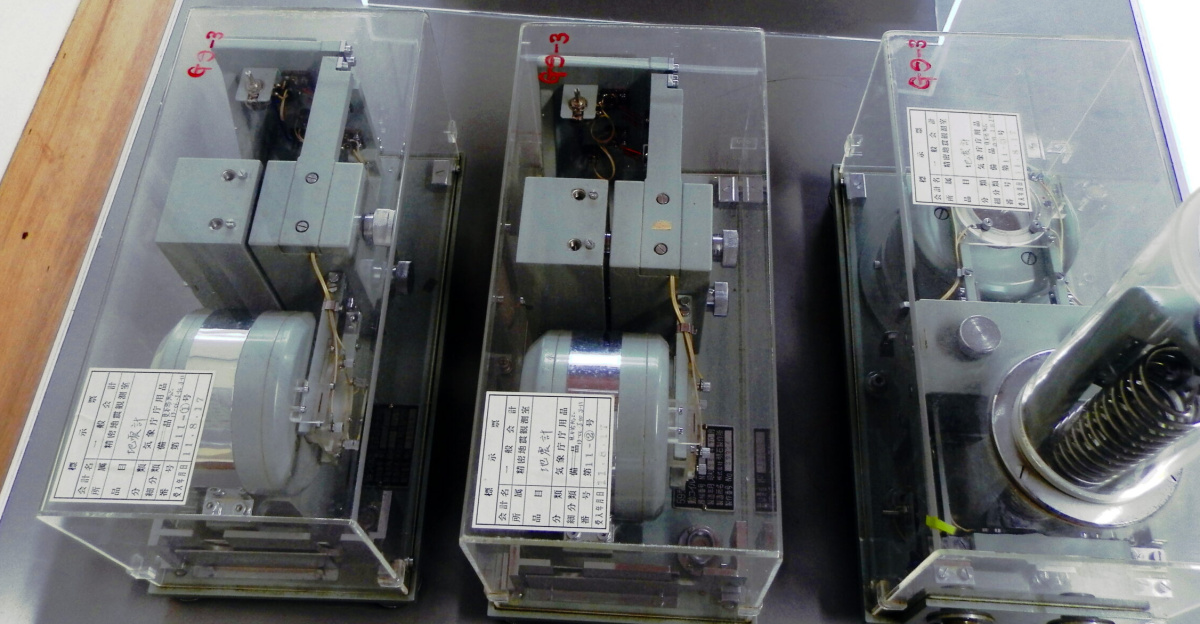

Although slow-slip events themselves release little or no felt shaking, they are frequently accompanied by tremor: small, low-frequency vibrations recorded by sensitive seismometers. These tremors are concentrated in bands beneath northern Washington and Vancouver Island, where regular “tremor swarms” point to active stress transfer deep within the crust.

Tremor observations are increasingly detailed. In recent years, seismologists have identified notable clusters in Northern California and Southern Oregon as well, expanding the map of where the plate boundary is creeping at depth. Because tremor activity correlates with motion along the fault, it offers a way to track how and where strain is accumulating even when no conventional earthquakes are occurring.

Whether tremor can serve as a reliable warning signal remains under study. Comparisons with other subduction zones, including regions of Chile that experienced a major quake in 2014, suggest that changes in tremor patterns might precede some large events. In Cascadia, any consistent link between tremor spikes and imminent rupture has yet to be demonstrated, but the behavior of these signals is now a central focus of monitoring.

Slow compression of the coastline

At the surface, satellites and ground-based GPS tell a steady, unsettling story: the Pacific Northwest is being squeezed. Stations anchored across the region show the coastline inching eastward as the Juan de Fuca plate subducts beneath North America. Over years, these shifts are measured in millimeters; over centuries, they add up.

Because the Cascadia fault is largely locked, the overriding plate is bending under the compressive force. Cities such as Portland and Seattle are slowly shifting, a sign of strain building along the plate boundary since the last major rupture in 1700. Geodetic models based on these measurements indicate that when the fault finally slips, the coastal margin could drop by around six feet in places, permanently reshaping the landscape and amplifying tsunami impacts.

GPS instruments also capture sudden changes in motion during slow-slip episodes, revealing how stress is temporarily redistributed along the subduction interface. These observations give researchers a near real-time view of how the crust responds to deep movements and help refine estimates of which fault segments are most primed to fail.

Searching for subtle precursors

One of the central unknowns is whether Cascadia will offer clear warning signs before a megaquake. In some subduction zones, sequences of foreshocks have preceded major events, but Cascadia’s behavior is difficult to assess because it has been quiet for more than 325 years.

Evidence from Tohoku and other regions suggests that slow-slip events and tremor changes may act as precursors in the absence of traditional foreshock swarms. That possibility has led researchers to broaden their search for signals beyond direct shaking. In several parts of the world, scientists have reported changes in groundwater chemistry before large earthquakes, including shifts in dissolved elements in Iceland and radon anomalies in Kamchatka. These changes are thought to result from microfractures opening under stress, altering how water flows through rocks and how gases escape.

Cascadia does not yet have a dense groundwater monitoring network capable of capturing such patterns on a regional scale. Some experts argue that installing chemical and gas sensors in key aquifers, alongside existing GPS and seismic instruments, could provide another line of evidence for evolving stress on the fault.

Interconnected faults and wider risks

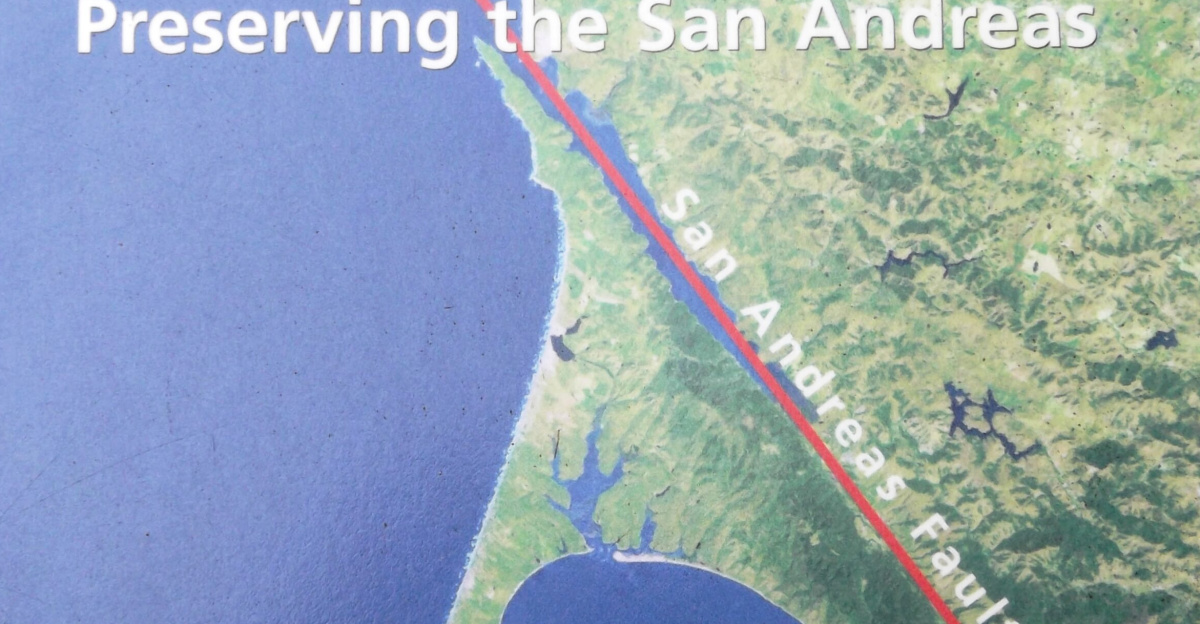

Cascadia does not exist in isolation. Geological records and modern studies indicate that a large rupture there could influence neighboring fault systems, potentially affecting the San Andreas Fault to the south and other offshore structures such as the Gorda Ridge. Recent earthquakes near the southern end of Cascadia highlight how stress can migrate along linked plate boundaries.

Models show that even a partial rupture of Cascadia could produce a magnitude 8.0 earthquake, with strong shaking over a broad area and possible triggering of nearby faults. Detailed mapping has revealed that the subduction zone is segmented, and these segments may fail together or in sequence. The section beneath Seattle and Tacoma is of particular concern because of its shallow angle, which brings the locked portion of the fault closer to densely populated areas and increases the expected intensity of shaking if it slips.

Researchers are also examining more unconventional clues, including changes in radon emissions and even animal behavior, both of which have been documented ahead of some earthquakes elsewhere. Such indicators remain uncertain and require careful baseline measurements and testing, but they illustrate the breadth of approaches being explored to gain any advance insight.

For now, the most robust signals come from slow-slip cycles, tremor swarms, and high-precision measurements of crustal deformation. Together, these data show that the Cascadia Subduction Zone is locked, stressed, and capable of producing one of the most consequential earthquakes on Earth. The challenge for scientists and policymakers is to translate these scientific findings into practical preparedness, building systems that can respond quickly if early warning signs emerge and strengthening communities and infrastructure along a coastline whose long-term future will be shaped by this powerful buried fault.

Sources:

“Cascadia Subduction Zone: Science and Seismic Hazards.” U.S. Geological Survey, 2023.

“Increased Flood Exposure in the Pacific Northwest Following a Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquake.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 2025.

“Cascadia Subduction Zone, One of Earth’s Top Hazards Comes Into Sharper Focus.” Columbia Climate School News, June 2024.

“The Pacific Northwest Geodetic Array: Real-Time GPS Monitoring of Crustal Deformation.” Central Washington University Geodesy Laboratory, 2024.