A rupture of the Cascadia Subduction Zone would cause the Pacific Northwest coastline to drop by up to six feet. Following the quake, models predict a tsunami up to 100 feet high could inundate the shore.

Estimates project 13,000 fatalities, significant infrastructure damage, and billions of dollars in losses. This seismic hazard is an active concern, with research indicating the event may occur within the current geologic timeframe.

1. The Silent Slip

Deep beneath the Pacific Northwest, slow-slip events occur approximately every 14 months. These gradual shifts in tectonic plates are potential precursors for a Cascadia megaquake.

Unlike standard earthquakes that release energy in seconds, slow-slips unfold over weeks. Detectable only by high-precision GPS, scientists have linked these events to major earthquakes, such as Japan’s 2011 Tohoku quake.

The Strain Accumulation

When separate slow-slip zones merge, the risk increases. A 2013 event demonstrated that when these fronts coalesced, slip rates increased eightfold.

This acceleration indicates that fault movement can intensify rapidly. Scientists continue to monitor these patterns closely to determine if they signal an impending rupture.

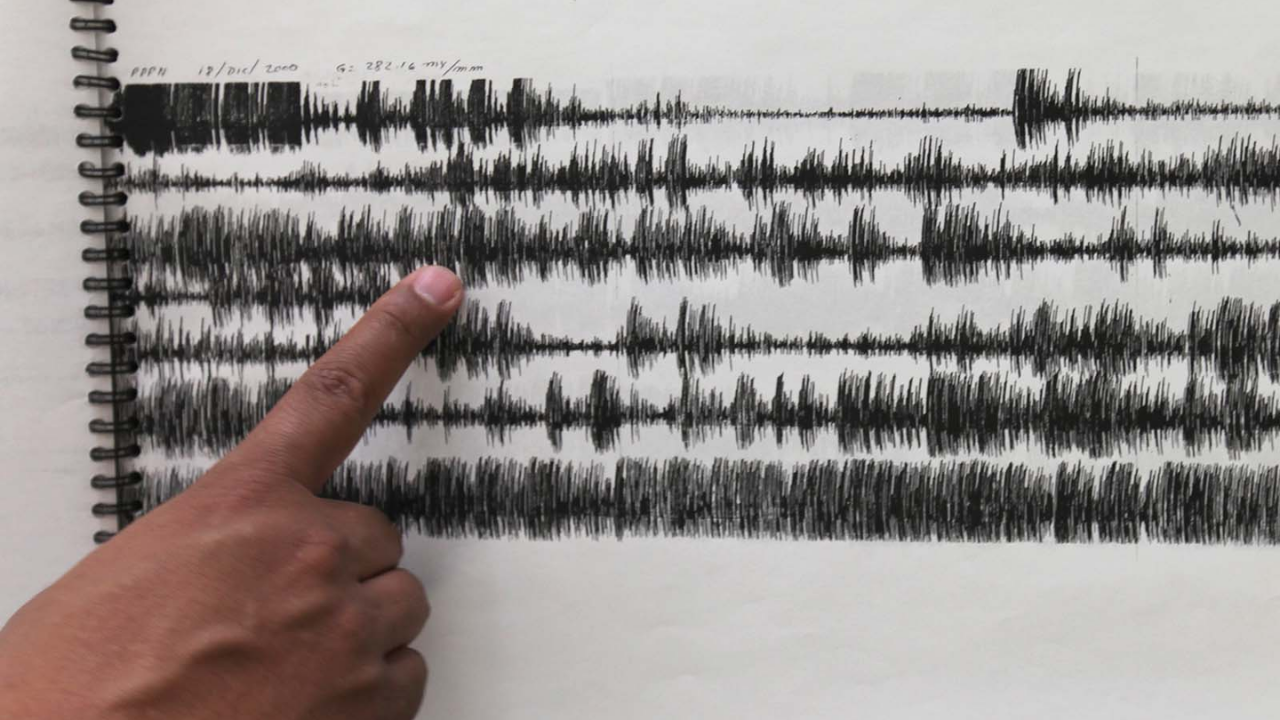

2. Tremor Activity

While slow-slips are aseismic, they are often accompanied by tremors. These are small vibrations recorded by seismometers, directly resulting from slow-slip movements.

Regular tremor swarms are recorded across Cascadia, particularly from northern Washington to Vancouver Island. These tremors serve as an indicator of stress transfer beneath the surface. Recent tremor spikes have drawn increased attention from seismologists.

Tremors as Precursors

Tremors correlate with tectonic plate movement, providing insight into fault behavior. Scientists track these signals to assess fault instability.

Recent analyses have identified notable tremor patterns in Northern California and Southern Oregon. These movements suggest significant activity at depth, potentially signaling stress accumulation along the Cascadia fault.

3. Coastal Compression

Satellite data confirms the Pacific Northwest is deforming. GPS stations show the coastline moving eastward, compressed by the Juan de Fuca plate subducting beneath the North American plate.

This deformation indicates strain building along the locked fault line. When the fault eventually releases, the accumulated strain will result in a massive earthquake.

Geodetic Evidence

Structures in Portland or Seattle shift slightly eastward annually—a cumulative effect over centuries. Since the last major rupture in 1700, significant stress has built up.

When the fault releases, the coastline is projected to drop by six feet, permanently altering the topography. GPS stations also detect rapid changes during slow-slip events, offering real-time data on crustal movement.

4. Potential Foreshocks

The occurrence of foreshocks remains a subject of study. Evidence from other subduction zones suggests Cascadia may exhibit warning signs before a major event. Japan’s 2011 Tohoku earthquake followed slow-slip events.

While consistent foreshocks in Cascadia have not yet been established, tremor activity may provide early warnings similar to the pattern observed prior to Chile’s 2014 earthquake.

Seismic Quiet

The question of foreshocks is complicated by Cascadia’s seismic history; the region has been seismically quiet for over 325 years.

While it is possible Cascadia could rupture without a traditional foreshock sequence, slow-slip events and tremors may act as unconventional precursors, potentially offering days or weeks of lead time.

5. Groundwater Chemistry

Changes in groundwater chemistry have been correlated with seismic activity. In regions like Iceland, researchers have detected fluctuations in dissolved elements months before major earthquakes.

As crustal stress creates microfractures, water flow patterns and chemical compositions in aquifers can shift. These changes may serve as predictive indicators.

Hydrogeochemical Signals

In Kamchatka, radon anomalies in groundwater were identified as precursors to major quakes. While Cascadia lacks a widespread groundwater monitoring system, implementing one could provide significant lead time.

This data could facilitate emergency preparation and help mitigate risks to coastal infrastructure vulnerable to flooding.

6. Biological Indicators

Historical and scientific observations suggest animal behavior may change prior to earthquakes. Research from Italy indicates farm animals exhibit increased restlessness before seismic events.

During the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, reports documented elephants fleeing to higher ground.

Behavioral Anomalies

In a Northern Italy study, sensors on farm animals recorded increased activity up to 20 hours before an earthquake. Dogs, sheep, and cows became notably restless, providing predictive data.

Monitoring animal behavior in Cascadia could arguably provide residents with a short warning window before a megaquake.

7. Fault Zone Interactions

Earthquakes can affect multiple fault zones. Research indicates a Cascadia rupture could trigger seismic activity along the San Andreas Fault.

Historical records show that Cascadia events have been followed by earthquakes on adjacent lines. Recent activity along the Gorda Ridge, which links to Cascadia, highlights the interconnected vulnerability of the Pacific coastline.

Regional Seismicity

Recent seismic activity near the southern Cascadia Subduction Zone suggests stress redistribution across the fault system. A partial rupture of Cascadia could produce a magnitude 8.0 earthquake, affecting a broad area.

Monitoring secondary faults, particularly near the Gorda Ridge, is critical for forecasting the timing and extent of a potential megaquake.

8. Radon Emissions

Changes in radon gas emissions are a debated but potential method of earthquake prediction. Hypotheses suggest that increased radon levels, caused by stress fractures, may act as an early warning.

In Kamchatka, anomalous radon patterns were detected days before earthquakes. Establishing baselines in Cascadia would be necessary to distinguish earthquake-related anomalies from background fluctuations.

Gas Monitoring

Radon detectors could be strategically placed around Cascadia to identify precursors. These stations would provide a cost-effective tool to track subterranean changes alongside GPS and seismic data.

With further development, radon monitoring could offer critical lead time by identifying increasing stress along fault lines.

9. Fault Segmentation

Advanced mapping of the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals a segmented fault capable of rupturing in distinct sections. These segments may rupture simultaneously or sequentially.

The segment beneath Seattle and Tacoma is a primary concern due to its shallow subduction angle. A rupture here would generate intense shaking, posing a severe threat to major urban centers.

The Washington Segment

The shallow-angle subduction beneath Washington State places the fault zone closer to densely populated areas than initially understood.

A rupture of this segment would result in significantly stronger ground motion. continuous monitoring of tremors and GPS data is essential to detect signs of accelerated stress buildup.

Current Outlook

The precursors discussed—slow-slip events, tremor swarms, and GPS deformation—are currently observable. The Cascadia Subduction Zone poses a verified threat with severe consequences.

Projections indicate a high death toll and substantial economic disruption. Recognizing these scientific indicators is vital for preparedness and survival.

Sources:

“Cascadia Subduction Zone: Science and Seismic Hazards.” U.S. Geological Survey, 2023.

“Increased Flood Exposure in the Pacific Northwest Following a Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquake.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 2025.

“Cascadia Subduction Zone, One of Earth’s Top Hazards Comes Into Sharper Focus.” Columbia Climate School News, June 2024.

“The Pacific Northwest Geodetic Array: Real-Time GPS Monitoring of Crustal Deformation.” Central Washington University Geodesy Laboratory, 2024.