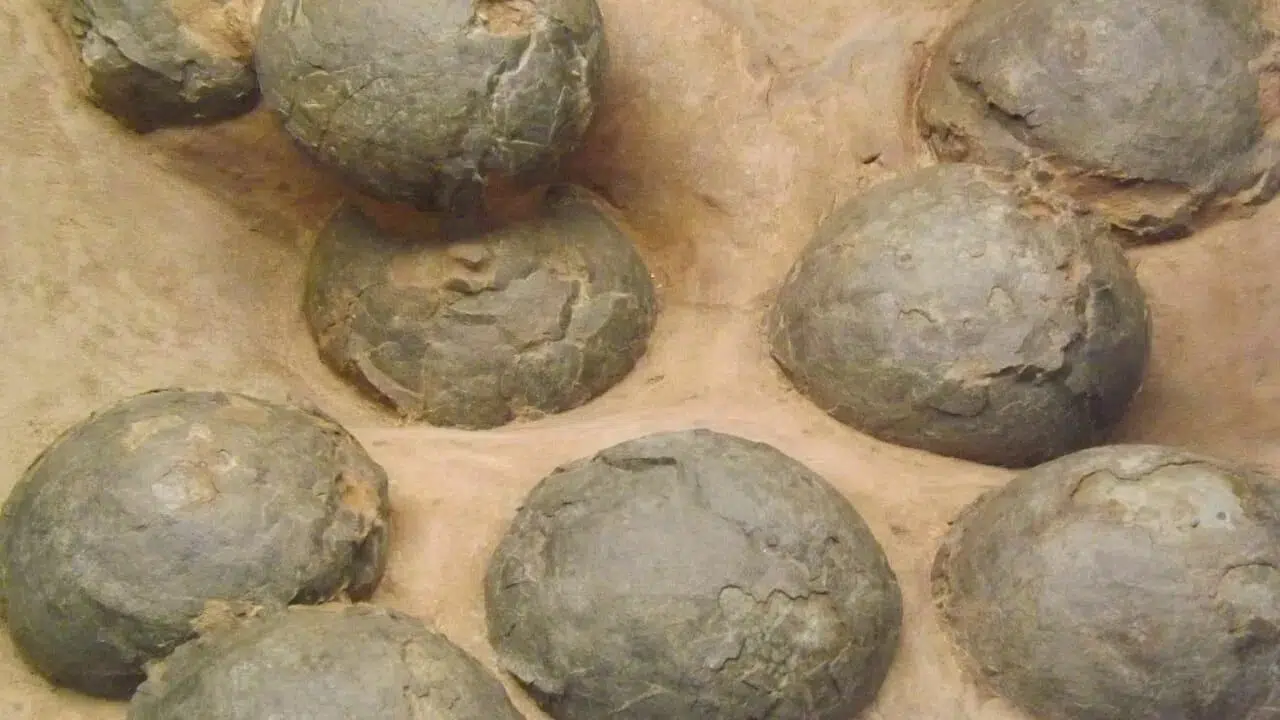

Paleontologists recently discovered four perfectly preserved titanosaur eggs in central Spain, dating back 72 million years. The team unearthed these eggs at the Creta in Poyos site near Guadalajara.

The eggs contain rare microstructures that scientists can study to gain insight into dinosaur reproduction and prehistoric environments.

This discovery marks a turning point for European paleontology, as major finds remain relatively uncommon compared to those in the Americas and Asia.

Where Giants Nested

The Creta in Poyos excavation site is located in Guadalajara province, within Castilla-La Mancha.

Paleontologists Francisco Ortega and Fernando Sanguino from UNED led the research team with regional government funding.

Scientists have relocated the eggs to the Palæontological Museum of Castilla-La Mancha (MUPA) in Cuenca, where visitors can now view them on display. The museum’s collection showcases these remarkable Cretaceous-era specimens.

A Rare Window into Deep Time

Most dinosaur eggs fossilize into broken shells or flat impressions, losing important structural details.

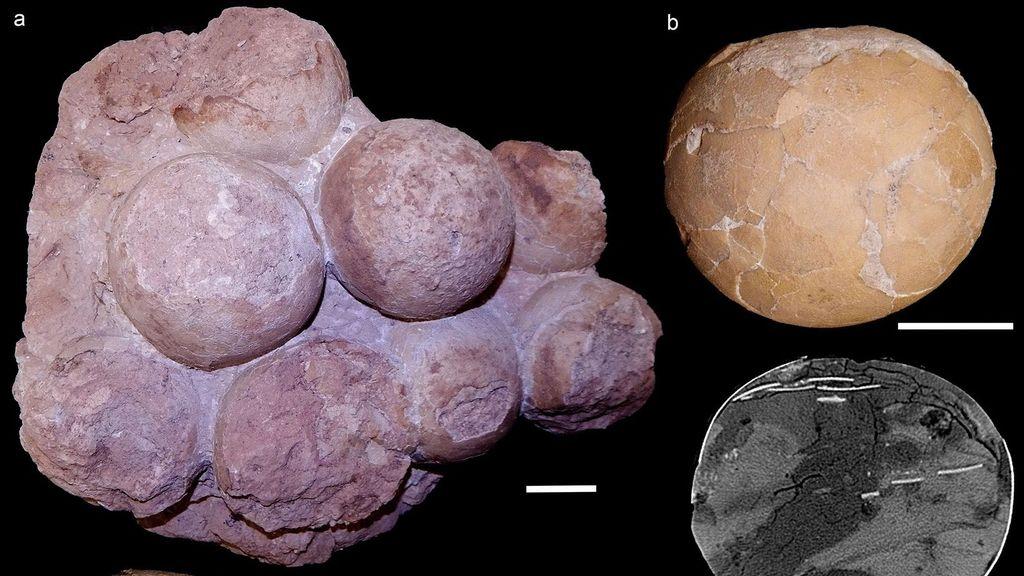

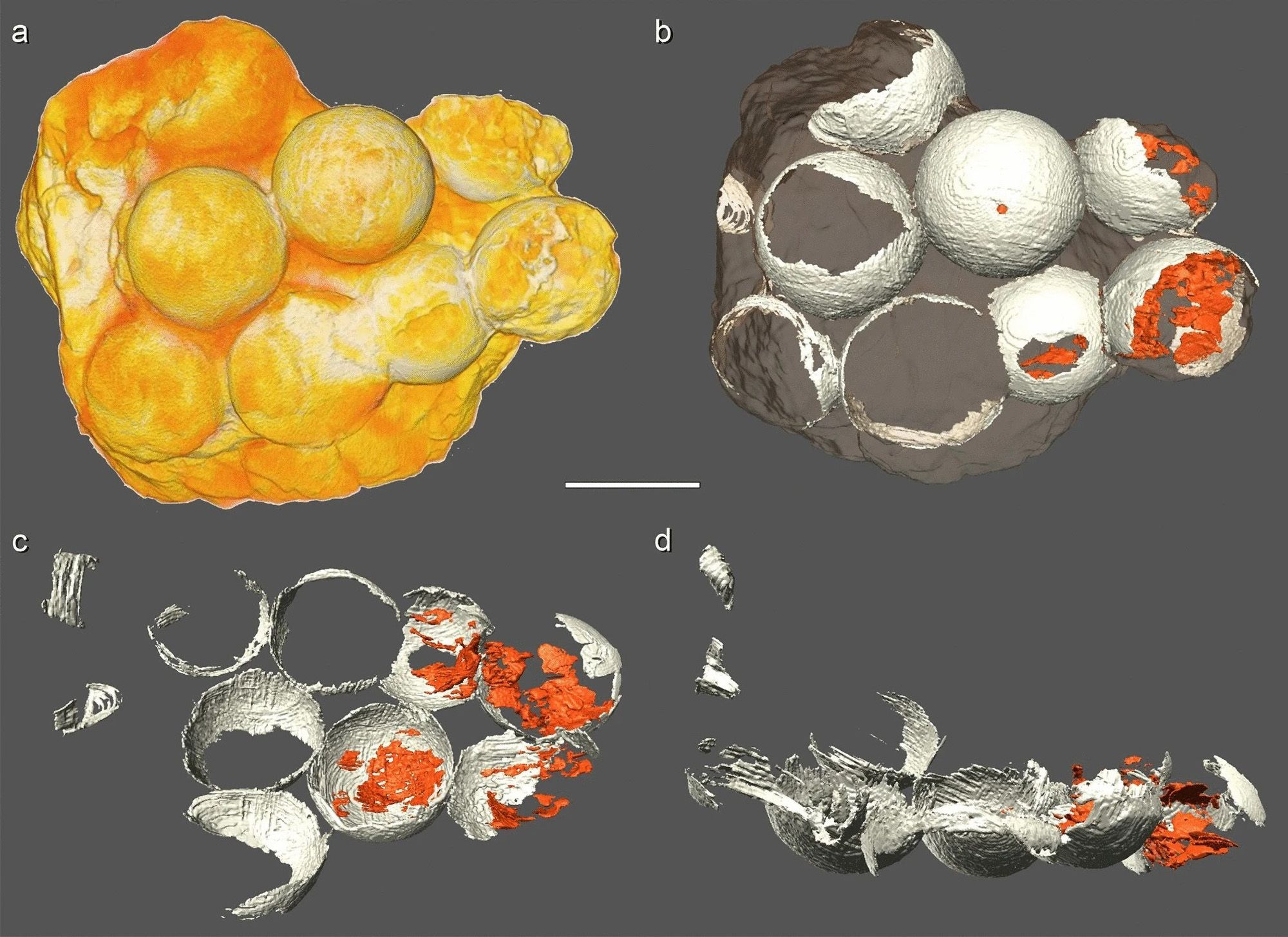

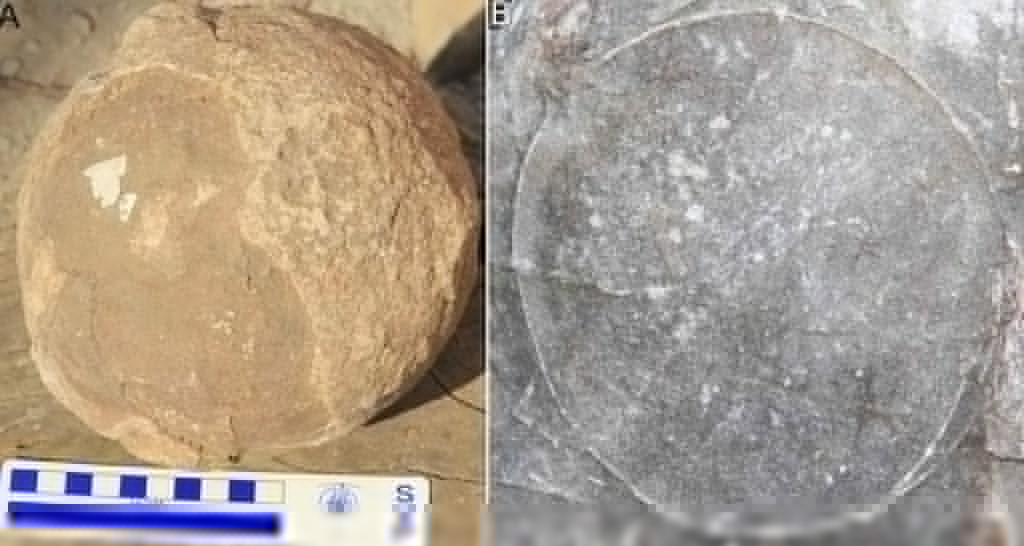

These four eggs retained exceptional preservation, complete with tiny spheroids, porous channels, and original shell shapes.

Researchers conducted a detailed microscopic analysis to reveal information about egg structure and thickness.

Scientists now possess a valuable asset that will unlock secrets about dinosaur reproduction, development cycles, and how species interacted in ancient ecosystems.

The Species Identity Mystery

Paleontologists identify fossil eggs by comparing shell thickness, texture, crystal patterns, and size to known species.

The Poyos eggs presented a puzzle: scientists found two distinct egg types in the same sediment layer.

The larger eggs with thin shells represent a new species, which researchers named Litosoolithus poyosi. The second type, Fusioolithus baghensis, appeared in younger deposits elsewhere.

The discovery of both species together surprised scientists worldwide.

A Rare Coexistence

Two different titanosaur egg species coexisted in a single sediment layer—an exceptionally rare phenomenon.

Litosoolithus poyosi stands out because it produced enormous eggs with unusually thin shells, unique among known titanosaurs.

Fusioolithus baghensis represents a different titanosaur lineage.

Scientists now wonder: Did two species nest together? Did environmental factors attract multiple species? Or did geological processes mix remains from different time periods? Each answer reveals different information about Cretaceous ecology.

The Spanish Recognition

In November 2025, Carmen Teresa Olmedo, Deputy Minister of Culture and Sport, unveiled the discovery at an official ceremony.

She called it “of worldwide significance” and “extremely exceptional.” This recognition brings practical benefits, including increased funding for excavation, international research opportunities, and enhanced site protection.

Spain’s growing prominence in paleontology is reflected in major discoveries at Lo Hueco, Morella, and the Ebro Basin, which prove that the Iberian Peninsula contained diverse dinosaur communities throughout the Cretaceous.

Reshaping European Paleontology

For decades, scientists considered European titanosaurs rare visitors. Most of Europe’s dinosaurs belonged to smaller theropods, ankylosaurs, and hadrosaurs.

New evidence from Poyos reveals a different picture: titanosaurs represented significant and widespread populations in Iberian ecosystems.

The discovery of nesting sites with multiple titanosaur species proves these animals reproduced successfully in Europe.

Researchers now understand that earlier assumptions about the rarity of titanosaurs reflected preservation bias and incomplete field surveys, rather than the actual absence of titanosaurs from ancient Europe.

Reproductive Biology Unlocked

The egg shells themselves tell stories. Their thickness, porosity, and mineral content reveal how much water and oxygen passed through during development.

The size variation among eggs suggests either the presence of different species or size differences within a single species.

The pore channels indicate that titanosaur eggs required oxygen exchange, similar to modern reptile and bird eggs.

Dr. Lisa Nguyen from the American Museum of Natural History notes these discoveries “deepen our understanding of ancient reproductive strategies and environmental adaptations.” The eggs unlock secrets about 50-ton dinosaurs.

Environmental Preservation Puzzles

How did these eggs survive 72 million years while most disappeared? Favorable conditions: rapid burial in fine sediment, minimal disturbance, and chemistry that preserved original structures.

The Poyos site contains Upper Cretaceous sediment where seasonal floods rapidly buried nesting areas. Ancient soil layers created perfect conditions for egg burial and fossilization.

Paleontologists call this a “paleontological sweet spot”—rare circumstances where fragile remains achieve exceptional preservation rather than decomposing or eroding away.

The Size Anomaly

Litosoolithus poyosi breaks an evolutionary rule. Typically, larger eggs develop thicker shells to prevent breakage and water loss.

This species produced enormous eggs but with unusually thin shells—a combination normally found only in small sauropods or birds.

Scientists question whether these thin-shelled eggs represented adaptation to specific conditions, an evolutionary experiment that failed, or unique reproductive constraints.

The anomaly suggests that titanosaurs employed diverse reproductive strategies beyond what would be expected from body size alone.

The 6-Million-Year Gap

These eggs date back 72 million years, precisely 6 million years before the asteroid impact that ended dinosaur dominance.

This timing carries profound significance: these animals nested during the Earth’s final chapter of dinosaurs.

The 6-million-year span allowed populations to persist and reproduce, yet it remains brief in geological terms.

Scientists question whether these animals survived until the extinction event or abandoned the site earlier. The healthy nesting clutches suggest the population thrived with ecological stability just before extinction.

Institutional Response

Following the announcement in November 2025, Castilla-La Mancha moved quickly to protect and study the eggs. MUPA constructed a new climate-controlled display case to preserve the fossils while allowing public access.

UNED’s research team launched detailed studies including shell analysis, isotope testing, and evolutionary modeling.

These efforts strike a balance between scientific investigation, heritage preservation, and public education. International research teams have already expressed interest in collaborative projects studying these remarkable specimens.

Research Ripple Effects

The discovery sparked new survey work across the Iberian Peninsula as paleontologists revisited previously unproductive sites.

Museums reexamined collections, reclassifying “unknown sauropod remains” with new knowledge about titanosaur diversity.

Spanish and Portuguese universities received increased funding for Cretaceous research. Scientists now reexamine similar egg specimens from other European sites, potentially identifying additional Litosoolithus poyosi examples.

This cascading effect illustrates how a single major discovery generates funding and research momentum across entire scientific fields.

Competing Interpretations

Paleontologists debate the dual-species discovery. One group emphasizes ecological coexistence, where two species nest together during the same season, suggesting shared preferences or tolerant social structures.

Another interpretation emphasizes temporal separation: eggs deposited during different seasons or years are then mixed by sediment transport.

A third perspective proposes that Fusioolithus baghensis represents reworked material—older eggs that were eroded and redeposited during floods.

Each interpretation carries a different ecological meaning. Researchers continue high-resolution dating and spatial analysis to distinguish between these competing hypotheses.

What Happens Next?

Scientists now ask: How many undiscovered paleontological sites remain across Europe’s Cretaceous deposits? The Iberian Peninsula spans thousands of square kilometers with exposed Late Cretaceous sediment, yet only a handful have received intensive study. Climate change, development, and erosion continuously destroy fossil-bearing layers. Researchers race against time to survey sites before they weather away or disappear. The Poyos success demonstrates that major discoveries remain achievable. Future priorities include conducting systematic surveys, fostering international collaboration, and securing long-term excavation funding.

Phylogenetic Placement

Teams currently conduct advanced analysis to determine how Litosoolithus poyosi relates to other titanosaur eggs globally.

Researchers compare specimens from Argentina, India, China, and other sites with preserved nesting areas.

This phylogenetic study reveals patterns of shell evolution and potential biogeographic trends across continents.

Preliminary findings suggest Litosoolithus poyosi occupies a unique evolutionary position. Isotopic analysis of the eggs will reveal data about ancient rainfall, temperature, and the diet of nesting females.

Museum Economics and Heritage Tourism

The Poyos discovery transformed MUPA into a major paleontological destination, attracting more visitors and international interest.

The museum markets itself as home to “the world’s most carefully preserved titanosaur eggs.” Increased tourism generated economic benefits through visitor spending and educational programs.

Regional and national funding agencies now prioritize paleontological research more highly.

Museums across Spain are reinvesting in their collections and research staff, recognizing both the scientific value and market appeal of Cretaceous discoveries.

Public Reaction and Misinformation

Social media engagement varied widely, with headlines ranging from accurate to wildly sensationalized. Some outlets falsely claimed 71 eggs at the site—a number contradicted by official sources and academic publications.

This illustrates how discoveries can become misinformation during media circulation without proper fact-checking. The actual four eggs possess greater scientific value through their exceptional preservation than large quantities of poorly preserved remains.

Museums and institutions responded by promoting direct engagement with primary sources and peer-reviewed literature, rapidly correcting misinformation online.

European Titanosaurs

The Poyos eggs complete a narrative shift over 20 years. Scientists once considered European titanosaurs rare curiosities.

Progressive discoveries altered this paradigm: species like Qunkasaura and Garumbatitan demonstrated that European titanosaurs reached substantial sizes. Nesting sites like Lo Hueco revealed reproductive behavior.

Multiple fossil localities have established a consistent presence of titanosaur throughout Late Cretaceous Iberia. The Poyos eggs represent viable, reproducing populations with species diversity.

Similar shifts occur repeatedly in paleontology: dinosaurs, marine reptiles, pterosaurs, and early mammals all revealed richer diversity as scientists accumulated discoveries.

Why This Matters

Four preserved eggs from 72 million years ago teach us a valuable lesson: ancient biodiversity exceeded what incomplete fossil records reveal.

These eggs prove Iberian titanosaurs reproduced successfully, coexisted with competing species, and thrived in European environments during the Cretaceous’s final chapter.

Scientists can now access reproductive biology and ecological interactions that were previously invisible in skeletal remains. Spain affirms its position as a premier destination of the Late Cretaceous period.

These eggs remind us that paradigm-shifting discoveries remain possible whenever we carefully and thoroughly examine geological records.