In modern industry, a single misjudged product can push even established companies to the brink. From Ford in the 1950s to Tesla in the 2010s, projects launched with high expectations instead triggered lawsuits, bailouts, and in some cases the collapse of entire brands. Together, these cases trace a pattern of overconfidence, technical overreach, and ignoring consumers until it is too late.

Edsel and Pinto: Ford’s Twin Cautionary Tales

Ford’s 1958 Edsel was supposed to redefine the mid-range American car. The company poured an estimated $250 million into development—roughly $2.5 billion in today’s money—and forecast 200,000 annual sales. Instead, buyers recoiled from its polarizing vertical grille and the timing could not have been worse: the model arrived just as the 1958 recession dampened demand for big, ostentatious cars. Dealers were left with lots full of unwanted vehicles, and the brand sold only 44,000 units in its second year. Ford killed the Edsel after just 118,000 cars in total, writing off a massive investment and reassessing its entire product strategy.

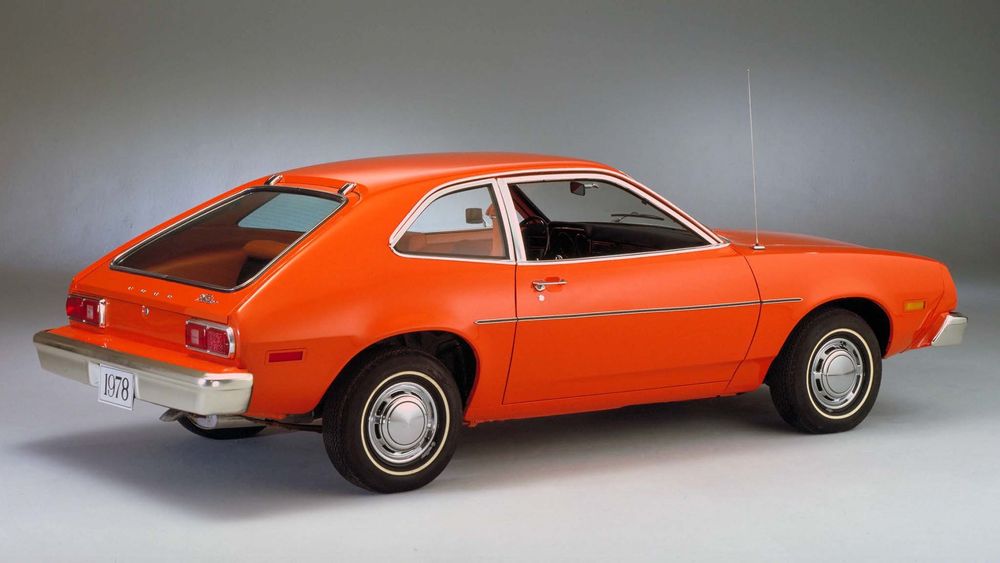

A little over a decade later, Ford faced an even more damaging crisis with the Pinto. Launched in 1971 as a low-cost compact, the Pinto’s fuel tank sat directly behind the rear axle and was vulnerable to rupturing in relatively low-speed rear-end collisions. Company crash tests identified the danger, yet internal cost calculations concluded it would be cheaper to pay an estimated $50 million in legal claims than spend roughly $137 million to redesign or retrofit the tank. The decision led to more than 100 lawsuits. In the landmark Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Company case, a jury returned a $127.8 million verdict, later reduced but still accompanied by hundreds of additional claims. Legal costs and reputational damage turned the Pinto into one of the most notorious examples of prioritizing cost over safety.

Engines and Airliners: Rolls-Royce and Lockheed on the Edge

In aviation, ambitious engineering gambles nearly erased two major names. Rolls-Royce’s RB211 turbofan, built for Lockheed’s new L-1011 TriStar widebody, introduced a complex triple-spool design under a fixed-price contract of £230,375 per engine. Early prototypes were overweight, underpowered, and unreliable. Development spending rose to £170.3 million by September 1970, almost double the original estimate, and production costs exceeded what Rolls-Royce had agreed to charge. Each unit delivered locked in a loss.

By February 4, 1971, the company could no longer absorb the overruns and declared bankruptcy. The British government stepped in immediately, nationalizing Rolls-Royce and injecting emergency capital. Without that intervention, one of the country’s flagship engineering firms would likely have been dismantled. After years of refinement under public ownership, the RB211 ultimately evolved into a commercial success, powering fleets of airliners and restoring the company’s position—an outcome that underscored how a near-fatal misstep could still be transformed through sustained investment and technical fixes.

For Lockheed, the L-1011 TriStar itself became a long-running financial wound. By 1970 the company had committed $1.4 billion to the program. Delays in RB211 development pushed the aircraft’s entry into service back by two years, allowing rival McDonnell Douglas to capture the market first with its DC-10. Lockheed needed to sell around 500 TriStars to break even; by the time production ceased in 1984, only about 250 had been built, each sold at a loss. In 1971, with bankruptcy looming, the U.S. Congress approved an Emergency Loan Guarantee Act of up to $250 million to keep the company afloat. A mid-1970s bribery scandal that cost more than $1 billion in lost contracts further weakened the firm. In the end, Lockheed withdrew from commercial airliners altogether, concentrating on military and aerospace work instead.

Tesla, DeLorean, NSU: Innovation Meets Harsh Reality

Half a century after the Edsel, Tesla’s Model 3 nearly repeated the pattern of a make-or-break product almost breaking the maker. Chief executive Elon Musk championed an “alien dreadnought” factory dominated by robots and elaborate conveyor systems. In practice, the high level of automation increased complexity. Machines struggled with variation, and bottlenecks choked production. While Tesla promised to build 5,000 Model 3 sedans per week by late 2017, output months after launch ran at roughly a tenth of that level. Cash flowed out quickly through 2017 and 2018. Musk later said the company came within about a month of bankruptcy, relying on emergency measures such as a hybrid human-robot assembly approach and a temporary assembly line in a tent structure to regain momentum and meet demand.

The DeLorean DMC-12 offered a different kind of high-profile collapse. Backed by about $100 million from the government of Northern Ireland to build a factory there, John DeLorean’s stainless-steel, gull-wing sports car was promoted as a symbol of regional renewal and projected at 30,000 units a year. In reality, only about 9,000 were built before the company went into receivership in February 1982, roughly a year after production began. The cars suffered complaints about modest performance and inconsistent quality. Investigators later uncovered a $23 million “GPD fraud” involving diverted development funds routed through a British firm. The government’s investment was largely wiped out, and John DeLorean soon faced separate criminal charges related to cocaine trafficking.

In Germany, NSU’s Ro 80 sedan showed how advanced engineering can still sink a brand. Launched in the late 1960s with a twin-rotor Wankel engine, aerodynamic bodywork, and four-wheel disc brakes, the car won Car of the Year honors and seemed to embody the future of automotive design. Yet NSU engineers had been aware of seal durability concerns in the rotary engine before launch and assumed they could resolve them quickly. In service, the rotor tip seals often failed before 25,000 miles, leading to catastrophic engine damage. Many owners required multiple engine replacements under warranty, draining NSU’s finances. By 1969, the once-promising company was near insolvency. Volkswagen acquired NSU and merged it with Auto Union to form Audi, and the NSU name vanished by 1977.

Government-Backed Dreams: Bricklin, Fisker, and the Aztek

Several later ventures illustrate how public backing and strong trends cannot compensate for flawed products. In Canada, Malcolm Bricklin’s SV1, another stainless-bodied sports car supported by more than $23 million in subsidies from the province of New Brunswick, promised safety and style but quickly developed a reputation for poor build quality and lackluster performance. Production began in 1974 and the firm filed for bankruptcy in 1975, leaving the province with heavy losses and few lasting economic benefits.

In the United States, the Fisker Karma arrived as a high-end plug-in hybrid pitched at environmentally conscious luxury buyers. Its real-world range and efficiency disappointed many owners, and high-profile battery incidents damaged confidence. During Hurricane Sandy, saltwater exposure led to electrical problems and 12-volt battery fires in parked vehicles. By November 2013, Fisker Automotive entered bankruptcy. Almost $193 million of a U.S. Department of Energy loan and hundreds of millions more in private capital were effectively wiped out, totaling close to $1 billion.

Even large, established automakers continued to misread their audiences. General Motors launched the Pontiac Aztek in 2001 as an early crossover, just as that category was gaining momentum. However, the vehicle’s styling drew sharply negative responses in research clinics, feedback that executives largely set aside. The Aztek’s appearance later became a cultural shorthand for awkward design, including a recurring role as the car of a struggling character in the series “Breaking Bad.” Over five model years, GM sold fewer than 120,000 Azteks. Combined with a broader strategy of badge-engineering and eroding distinctiveness across the lineup, the poor performance contributed to Pontiac’s financial weakness ahead of GM’s 2008–2009 restructuring. The Pontiac brand was discontinued in 2010.

Why These Failures Still Matter

Across these episodes, several themes recur: ambitious technology deployed before it is ready, leadership fixated on projections rather than customers, and a willingness to gamble with safety or public money in pursuit of speed or prestige. Companies that survived—such as Ford, Rolls-Royce, Lockheed, and Tesla—did so by eventually confronting those realities, modifying products, changing strategies, or accepting government help. Others disappeared or were absorbed. For today’s manufacturers, the enduring lesson is that bold ideas must be grounded in realistic engineering, transparent risk assessment, and close attention to the people expected to buy and use the products.

Sources:

EBSCO Research Starters (Law) — Court Finds That Ford Ignored Pinto’s Safety Problems

Taxpayer.net — Fisker Automotive is Auctioned Off: DOE Fails to Save Millions

Curious Droid — RB.211: The Engine That Sank and Then Saved Rolls Royce

SimpleFlying — The Rise & Fall Of The Lockheed L-1011 TriStar

Mosaic Tech — Tesla: From Brink of Bankruptcy (Twice) to World’s Most Valuable Automaker