Every fifteen minutes, on average, the ground moves somewhere in Alaska. Most of those quakes are too small to notice, but together they reveal a state under constant geologic pressure. That routine background shaking turned into a regional jolt last Saturday, when a powerful earthquake struck near the small coastal community of Yakutat and rippled hundreds of miles across Alaska and into Canada.

Seismic Hotspot on the Ring of Fire

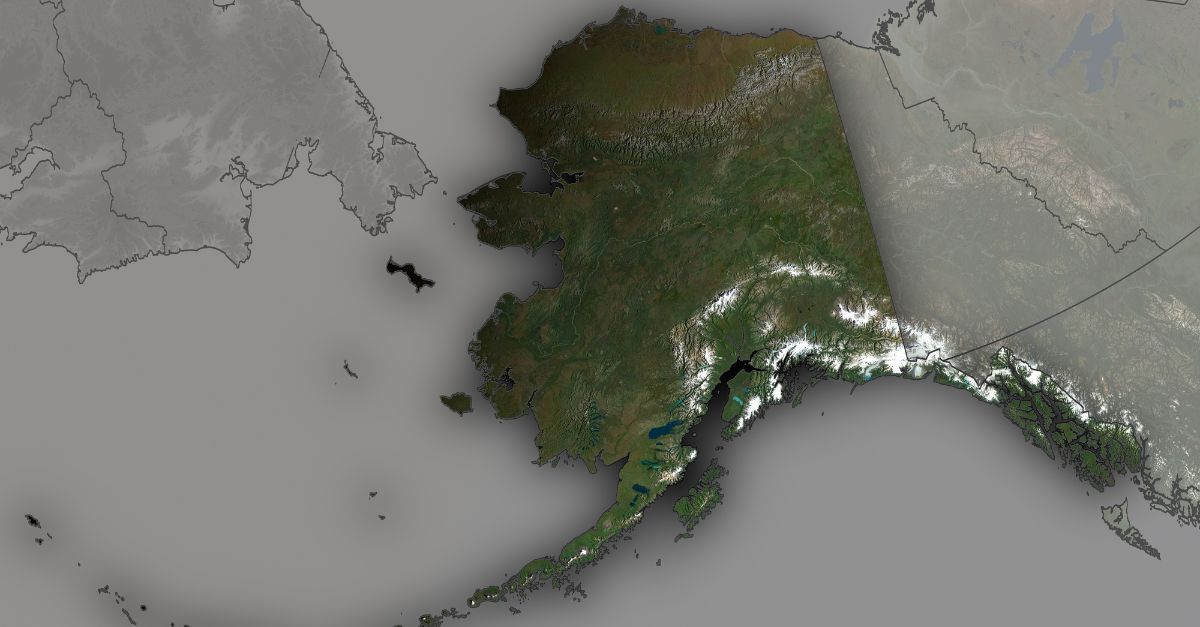

Alaska accounts for about 11 percent of the world’s earthquakes and 17.5 percent of those recorded in the United States. Most residents are used to tremors as part of daily life, far from the spotlight usually directed at California. Yet history shows how suddenly that familiarity can turn dangerous.

On March 27, 1964, a magnitude 9.2 earthquake ruptured beneath southern Alaska, the second-largest event ever recorded worldwide and the strongest in U.S. history. That disaster killed 139 people across Alaska and the Pacific Northwest and reshaped scientific understanding of plate boundaries in the region.

Alaska lies along the Pacific “Ring of Fire,” a 25,000‑mile belt that produces 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes and hosts roughly three‑quarters of its active volcanoes. Here, the Pacific Plate dives beneath the North American Plate, with the smaller Yakutat microplate adding further complexity. This constant convergence locks and slips along deep faults, ensuring frequent earthquakes. The uncertainty is not if they will occur, but when and where the largest will strike.

Saturday’s Mainshock and Immediate Impact

At 11:41 a.m. Alaska time on Saturday, December 6, 2025, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake ruptured the crust near Yakutat in southeastern Alaska. The U.S. Geological Survey located the epicenter about 56 miles north of Yakutat, at a shallow depth of roughly 6 miles.

The quake was felt as far as Anchorage, about 300 miles away, and across the border in Canada’s Yukon Territory. People in communities from Whitehorse to Haines Junction reported shaking. No tsunami warning was issued. Authorities reported no deaths, injuries, or significant structural damage in the hours after the event.

The earthquake’s relatively shallow depth helped transmit strong seismic waves across a wide area. Anchorage, with around 300,000 residents, experienced noticeable shaking despite the long distance from the epicenter. The sparsely populated nature of southeastern Alaska and the Yukon reduced the potential human toll. Yakutat itself has 657 residents, and Haines Junction has about 1,000, limiting exposure to falling objects or collapsing structures.

How Residents and Experts Described the Shaking

Reports from those who felt the quake helped confirm what instruments recorded. Sergeant Calista MacLeod of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Whitehorse told the Associated Press that “it definitely was felt” and that many residents reported the event on online platforms. Her detachment received two 911 calls linked to the shaking.

Alison Bird, a seismologist with Natural Resources Canada, said that people reported items falling from shelves and walls but that no structural damage had been identified. These early accounts pointed to strong but not catastrophic shaking across a broad region, consistent with a major earthquake occurring far from dense population centers.

Inside the Aftershock Sequence and Risk Forecast

The most revealing part of the sequence unfolded after the mainshock. Within about forty minutes, significant aftershocks began. Over the next 24 hours, monitoring networks recorded 164 earthquakes in the vicinity of the original rupture. Many were small, but several exceeded magnitude 5.0. Seismologists confirmed at least two notable aftershocks, of magnitudes 5.3 and 5.0, which would be considered substantial events on their own in more crowded areas.

Magnitude 7.0 to 7.9 earthquakes are classified as “major,” capable of serious damage in built‑up regions. The magnitude scale is logarithmic: each whole‑number increase reflects about ten times more ground motion than the previous step. A magnitude 7.0 event therefore releases roughly ten times the energy of a 6.0. At only about 6 miles deep, Saturday’s mainshock sent strong waves through relatively thin crust, rather than dissipating energy at greater depth.

The USGS activated its Operational Aftershock Forecasting system soon after the earthquake. Austin Holland, Director of Operations at the Alaska Earthquake Center, explained that there remained “a very small chance that a larger earthquake could occur in the sequence,” reflecting standard protocol after any event of magnitude 7 or greater. These forecasts provide probabilities to guide emergency managers and public agencies.

For the coming year, the system estimated a 6 percent chance of another triggered earthquake of magnitude 7.0 or larger in the region. While that probability appears low, it is considered significant in earthquake forecasting. The same outlook gave a 32 percent chance of a magnitude 5.0 or greater aftershock. These figures account for shifting stress on faults surrounding the initial rupture, which can sometimes set off what seismologists term a triggered event.

Lessons from 1899 and the Long View

The Yakutat region’s history underlines why scientists are watching closely. In 1899, the area experienced a complex sequence that began with a major quake on September 3 and was followed within days by another major event on September 10, with magnitudes in the 8.2 to 8.6 range, along with additional large shocks around magnitude 7. The pattern showed how stress can transfer between neighboring fault segments, producing multi‑stage ruptures rather than a single isolated event.

Michael West, Alaska’s state seismologist, noted after Saturday’s earthquake that a magnitude 7.0 is “certainly sufficient to cause ground failures” and that landslides or damaged roadways might yet be discovered once remote terrain can be surveyed. In steep, mountainous regions, shaking of this intensity can trigger rockfalls and slope failures far from any towns.

The Alaska Earthquake Center, working with USGS and other partners, operates an extensive seismic network that records nearly every detectable tremor. In 2018, aided by new stations from the EarthScope Transportable Array, the state logged more than 54,000 earthquakes. That increase reflected better monitoring rather than a sudden surge in seismicity, revealing just how frequently Alaska’s crust shifts to relieve accumulated stress.

On average, Alaska experiences about one magnitude 7.0 to 8.0 earthquake each year and a magnitude 8.0 or larger about every thirteen years. Events such as the 1964 magnitude 9.2 Great Alaska Earthquake and the 1965 magnitude 8.7 Rat Islands quake highlight the region’s capacity for some of the largest ruptures on Earth. As aftershocks near Yakutat continue over the coming weeks and months, scientists will scrutinize their locations and patterns for any signs that stress is migrating onto adjacent faults.

For residents and officials, the latest event is both a reminder of the state’s restless foundations and an opportunity to refine emergency plans, infrastructure checks, and public awareness in advance of whatever comes next.

Sources:

CRMP.org, 2024; Alaska Earthquake Center

USGS Geological Survey

Wikipedia earthquake records

Newsweek, December 7, 2025

Alaska Earthquake Center monitoring reports

Earthquake Insights analysis