The Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions are bracing for a rare weather conundrum—two coastal snowstorms approaching at once. Meteorologists are at a loss, with models sharply disagreeing on their paths, timing, and intensity.

The National Weather Service and AccuWeather have issued warnings, but public anxiety is mounting.

As millions face uncertainty just 72 hours from impact, a pressing question remains: how prepared can we be when even the experts are unsure? Keep reading to uncover the potential risks ahead.

The Stakes for 65 Million

The I-95 corridor stretches from Maine to Virginia, connecting approximately 65 million Americans across the Northeast’s most economically vital region. This densely populated megaregion includes Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston—centers of commerce, government, and culture.

Any significant winter storm threatens travel gridlock, infrastructure strain, and economic disruption affecting multiple states simultaneously. Two storms arriving within 48 hours compound the risk exponentially.

If both systems track inland along the coast, accumulating snow could cascade into a multi-day crisis affecting transportation networks, supply chains, and emergency services across the corridor. The stakes have rarely been higher for a winter weather event with such compressed uncertainty.

Model Disagreement

Dual coastal storm scenarios are meteorologically complex because two low-pressure systems can interact, merge, or separate unpredictably. Traditional forecasting models—the European (ECMWF), American (GFS), and Canadian (CMC) systems—operate on different physics assumptions and computational grids.

When storms are rare or poorly sampled historically, model consensus collapses. AccuWeather meteorologist Alex Sosnowski noted that prediction guidance has been “changing its tune” repeatedly as new data arrived, with competing models sometimes suggesting entirely different outcomes within hours.

This phenomenon is not new, but its proximity to impact (late Wednesday, January 14) leaves little time for consensus to crystallize or for the public to adapt plans.

Previous Close Calls

The Northeast has experienced forecast surprises before. The January 2016 “Snowmageddon” and the January 2022 nor’easter both caught some residents off guard, despite advance warnings. However, those events had clearer tracks 5–7 days out.

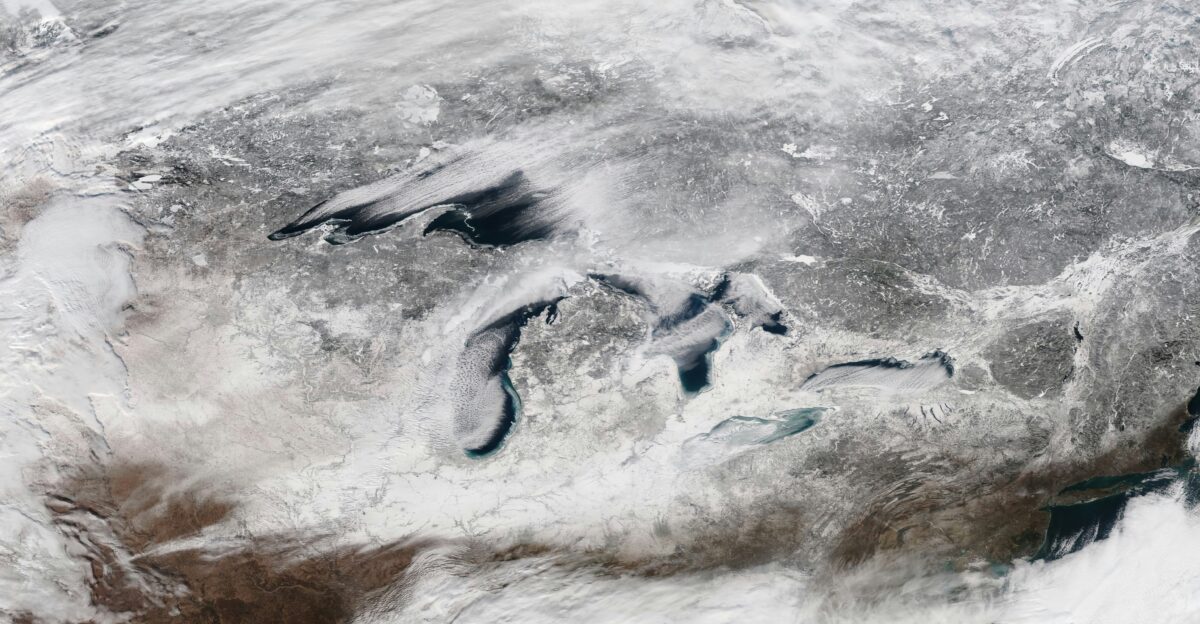

This dual-storm setup offers less historical precedent and fewer analogues in modern datasets. The Lower Great Lakes region is already bracing for lake-effect snow, confirmed through the period, which complicates the picture further.

As the system approaches, forecasters face mounting pressure to provide certainty they don’t yet possess. The tension between public demand for clarity and meteorological reality has seldom been starker.

The Candid Admission

On January 12, the National Weather Service made an unusually direct statement: “We don’t know the potential impacts to travel and infrastructure due to snow and wind, especially along the I-95 corridor.” This quote, posted across multiple official channels, represents a rare public acknowledgment of the limits of forecasting.

Rather than hedging with probabilistic language, the NWS stated outright that specifics—snowfall totals, exact track, timing precision—remain unknowable with high confidence. The statement was not reluctant or concealed but rather transparent scientific communication.

Yet the bluntness shocked many Americans accustomed to confident 10-day forecasts. For a region housing 65 million people, this admission underscored a sobering reality: modern meteorology has limits, even with 72 hours’ warning.

Northeast Impact Zone

The dual storms pose distinct risks by region. In Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, interior Northeast snowfall is nearly certain, with lake-effect enhancement from the Great Lakes adding localized heavy bands. The Central Appalachians (eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, western Virginia) will experience significant accumulation beginning late Wednesday.

However, the critical uncertainty centers on coastal New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and the Baltimore–Washington corridor—the I-95 spine itself.

If storms track 50 miles offshore, major cities evade significant snow. If they hug the coast, cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia face 8–14+ inches. This fine margin of difference translates to billions in economic impact and affects 30+ million people directly.

Commuter Gridlock Risk

The I-95 corridor handles 30+ million daily commutes, moving workers between Washington, D.C., and Boston. Major bottlenecks occur at Baltimore, the New Jersey Turnpike, and the Connecticut-New York border. A moderate snowstorm (6–10 inches) creates 4–6 hour delays.

A heavy event (12+ inches) can shut corridors for 12–24 hours. Double the storm frequency in 48 hours, and the recovery time extends exponentially. Airlines have already begun issuing travel waivers for flights January 14–17. Amtrak and regional transit systems are on heightened alert.

For the 20+ million Americans in the I-95 corridor workforce, a dual-storm scenario threatens not just commutes but payroll disruptions, supply-chain breaks, and emergency response strain. The human cost is immeasurable without clear forecasts.

Economic Spillover

Winter storm costs scale with uncertainty. The 2014 “Polar Vortex” winter cost the U.S. economy an estimated $5 billion in direct losses (heating fuel, road salt, emergency response, lost productivity). A major nor’easter hitting the I-95 corridor typically costs $50–100 million in direct damages.

A dual-storm event, depending on track and intensity, could exceed $200 million if both systems deliver heavy snow to major metros. Retailers lose foot traffic; supply chains snap; logistics hubs (Newark, JFK, Philadelphia ports) face operational delays.

Insurance companies and reinsurers are monitoring models closely. Stock markets typically dip during major Northeast disruptions, given the region’s outsized share of U.S. GDP. The financial stakes explain why the NWS statement shocked markets and corporate contingency planners alike.

Model Spread Visualization

As of January 12, the American GFS model predicted a coastal track with major-city impacts; the European ECMWF model suggested an offshore solution with minimal precipitation for I-95 metros; the Canadian CMC split the difference.

This 3-way disagreement is extreme for a 72-hour forecast window. Typically, models converge within 48 hours of a major event. Here, the model spread widened as new atmospheric data arrived, confounding forecasters.

Jon Porter, AccuWeather’s Senior VP of Forecast Operations, issued a statement acknowledging the difficulty: dual coastal storms introduce nonlinear interactions that standard models struggle to resolve in real time. The phenomenon highlights the gap between weather prediction science and public expectations of certainty.

The Confidence Collapse

A secondary consequence emerges from the NWS admission: public trust in meteorological guidance erodes when forecasters abandon numerical confidence ranges. Historically, the NWS issues probability cones (“70% confidence in track corridor X”) and probabilistic snowfall ranges (“4–8 inches, locally 10 inches possible”).

This language is precise and defensible. The phrase “We don’t know” signals the breakdown of these tools—a rarity that amplifies public anxiety. Social media flooded with complaints: “If they can’t tell us, why should we trust them?”

Some residents began ignoring official guidance entirely, instead relying on amateur storm chasers and private weather apps. This erosion of institutional trust—compounded by the arrival of the dual-storm system just hours away—creates a secondary crisis: informational disruption alongside meteorological

uncertainty.

Logistics and Supply-Chain Strain

Port authorities in New York, Newark, and Baltimore are preparing contingency plans. If dual storms deposit heavy snow on Wednesday night, Thursday operations could be suspended, cascading delays into Friday and the weekend.

Grocery retailers stocked distribution centers ahead of the storms, anticipating panic buying—but restocking trucks may not reach stores until Friday or Saturday if roads close. Natural gas suppliers are ramping up reserves; heating oil distributors are pre-positioned.

Hospitals are ensuring backup power and staff lodging for multi-day staff who may be stranded. These preparations themselves consume resources and time, driven by uncertainty rather than clarity. Some supply-chain managers expressed frustration: “We’re spending millions preparing for multiple scenarios we can’t distinguish. Better clarity would reduce waste.”

Government Activation

State emergency management agencies from Maine to Virginia activated emergency operations centers on January 12. New York Governor Kathy Hochul issued a pre-event disaster declaration to streamline resource mobilization if storms hit hard. New Jersey and Connecticut followed suit.

Federal emergency management liaisons were stationed in regional command centers. The National Guard was placed on standby in three states. These activations, triggered by forecast uncertainty rather than a confirmed major event, highlight the precautionary posture the system must adopt.

Some critics questioned the expenditure: “Are we over-preparing for a forecast that could miss the major cities entirely?” Others defended it: “If a dual-storm system hits I-95, the 48-hour response window is too short—we need to be ready now.”

Meteorological Humility

The NWS statement sparked a broader conversation about the limits of meteorological science. Dr. Paul Gross, chief meteorologist at the National Weather Service Eastern Region Office, gave an interview acknowledging that dual-coastal-storm scenarios “push our predictive models to their boundaries.”

He noted that climate change and shifting jet stream patterns may be introducing new storm morphologies forecasters haven’t seen historically, complicating model calibration. Other meteorologists, including researchers at MIT and Penn State, argued for investing in higher-resolution modeling and expanding observational networks (such as satellites and radiosondes) to better capture dual-storm interactions.

The NWS admission, rather than undermining professional credibility, opened a window into the working conditions of operational meteorology—a window many in the public hadn’t considered before.

Preparedness Verdict

By late January 13, with storms arriving in hours, the region had taken reasonable precautions. Road salt inventories were full; heavy equipment was staged; emergency shelters were prepped in major cities. Schools announced contingency closures for January 14–15, affecting 5+ million students. Major employers (Goldman Sachs, Microsoft offices in NYC) told staff to work remotely.

Airlines had issued weather waivers. Yet the persistent uncertainty meant no one could optimize preparation precisely. Resources were spread across multiple contingency plans. Some criticized this diffusion: “Preparation without clarity is costly and inefficient.”

Others countered: “Precision would be worse—if we’d guessed wrong, the outcome would be catastrophic.” The tension between preparedness and certainty remained unresolved heading into the storm event itself.

The Unfolding Question

As the dual storms approach on January 14–16, 2026, a fundamental question hangs over the Northeast: Can a technologically advanced society truly prepare for meteorological events at the boundary of predictability?

The NWS “We don’t know” statement crystallizes a paradox—modern weather satellites, supercomputers, and data networks have pushed forecasting to unprecedented accuracy for most events, yet dual-storm scenarios remain stubbornly opaque.

In the coming weeks, meteorologists will study what the storms actually delivered versus what models predicted. If major cities are spared, forecasters will face criticism for over-warning. If cities are hit hard, criticism will focus on insufficient warning detail.

Either way, the 65 million Americans in the corridor will have experienced an uncomfortable truth: even with science and technology, some natural events refuse to be tamed by prediction. The lesson may prove as valuable as the forecast itself.

Sources:

National Weather Service Official Statements, 12 Jan 2026

AccuWeather Forecast Operations & Senior VP Jon Porter, 12 Jan 2026

I-95 Corridor Coalition Data via National Academies, 2021

USA Today Weather Coverage, 12–13 Jan 2026

Reuters Weather & Transportation Reporting, 12–13 Jan 2026

Yahoo News / AOL News Weather Syndication, 12 Jan 2026