Arctic permafrost contains one of Earth’s largest carbon reservoirs, holding roughly 1,600 gigatons of organic carbon—about twice the amount currently in the atmosphere. As temperatures rise, thawing permafrost allows microbes to access this long-frozen material.

Alaska, where permafrost underlies most of the land, is warming rapidly. Scientists warn that carbon released from thawing ground could significantly accelerate climate change if feedbacks remain underestimated.

Summer Lengthens the Risk

Arctic warming is occurring several times faster than the global average, with warmer conditions extending further into spring and autumn.

This lengthening of the thaw season matters more than short-lived heat extremes. Longer warm periods allow deeper soil layers to thaw, increasing the time microbes have to metabolize ancient organic matter. These extended seasons are now considered a critical driver of future permafrost carbon emissions.

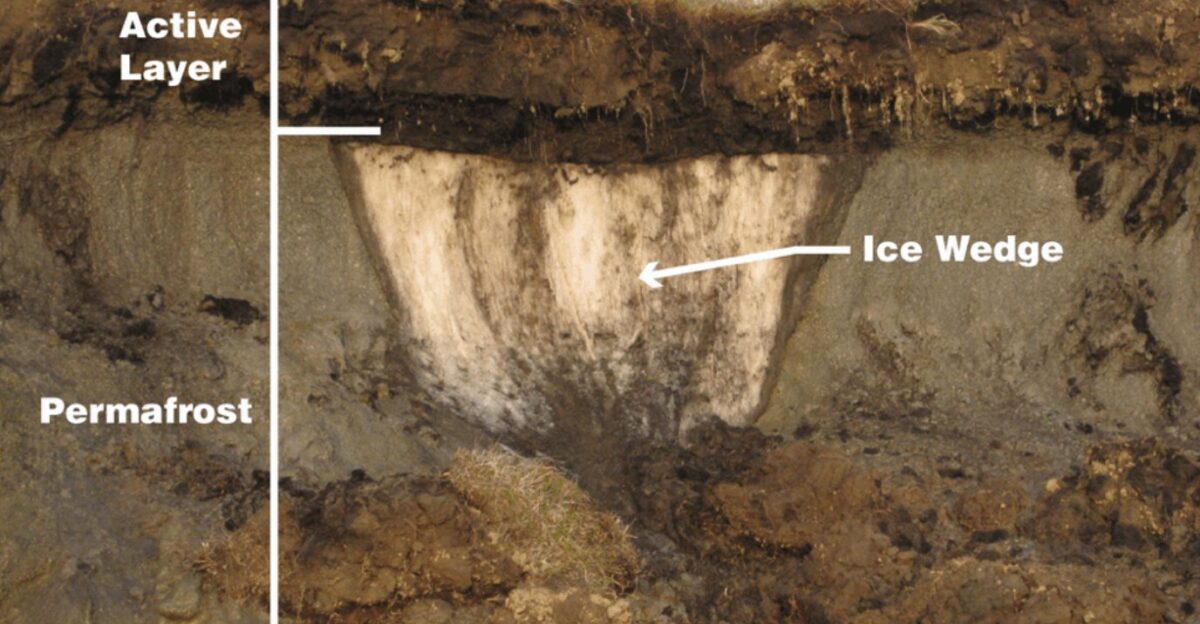

What Permafrost Preserves

Permafrost is ground that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years and covers nearly one-quarter of the Northern Hemisphere. Much of it has remained frozen since the late Pleistocene, locking away plant and animal remains for tens of thousands of years.

These frozen soils preserved vast carbon stocks by limiting microbial activity—until warming conditions began to disrupt that balance.

Pressure Builds Beneath the Surface

As permafrost thaws, once-stable landscapes can abruptly collapse, exposing deeper carbon-rich layers. Studies show that parts of the Arctic-boreal zone are already shifting from net carbon sinks to net sources.

Abrupt thaw events, wildfires, and erosion can dramatically increase emissions beyond gradual thaw alone, accelerating the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

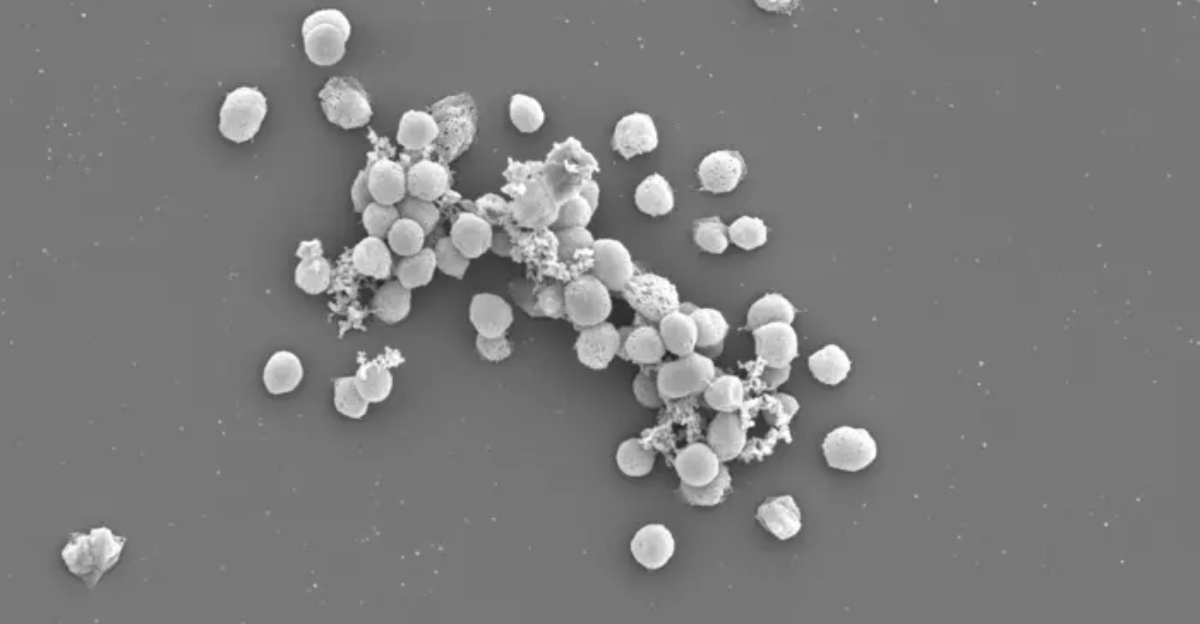

Microbes From the Ice Age

In 2025, University of Colorado Boulder researchers revived microorganisms frozen for 37,900–42,400 years from permafrost cores drilled more than 20 meters deep near Fox, Alaska. The samples came from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Permafrost Research Tunnel.

Once thawed under controlled conditions, the microbes demonstrated that ancient life can remain viable and metabolically active after tens of millennia.

The Six-Month Delay

After thawing, the microbes showed minimal activity for roughly six months, even at temperatures similar to modern Arctic summers. Researchers tracked metabolism using deuterium-enriched water and observed extremely slow cell replacement rates early on.

Then, microbial activity surged, forming visible biofilms and rapidly producing carbon dioxide and methane—revealing a delayed but powerful response.

Why the Lag Matters

This lag-then-surge pattern challenges current climate models, which often assume emissions rise immediately with thaw. Instead, warming events may trigger delayed emissions months later, making impacts harder to detect in real time.

If widespread across the Arctic, these delays could mean that future greenhouse gas releases are already “locked in” long before they are measured.

Alaska’s Unique Exposure

Permafrost underlies approximately 85% of Alaska’s land area, placing the state at the forefront of these changes.

As the active layer deepens, microbes gain access to increasingly old carbon pools. The study found that revived ancient microbes can reach activity levels comparable to modern soil microbes, indicating that age alone does not limit their impact.

Human Stakes in the Arctic

Between 10 and 20 million people live in or near permafrost regions across Alaska, Canada, Russia, and northern Europe.

Thawing ground threatens buildings, roads, pipelines, and water systems. Communities often experience damage before emissions are even measured, making permafrost thaw both a climate and infrastructure challenge.

Methane Isn’t Uniform

Not all thawing permafrost behaves the same. In some drier, oxygen-rich soils, methane-consuming microbes can outcompete methane producers, slightly reducing emissions.

Genomic studies show that soil moisture and oxygen availability strongly influence outcomes. While wet, waterlogged areas tend to emit methane, drier regions may partially offset those releases.

Limits of One Study

Researchers caution against overgeneralizing results from a single location. Alaska’s permafrost differs biologically from Siberian, alpine, or peat-rich regions.

Lead author Tristan Caro emphasized that only a small portion of the Arctic has been sampled, and microbial responses may vary widely depending on soil chemistry, moisture, and temperature history.

Expanding the Research

To address these gaps, researchers are shifting attention to “shoulder seasons” such as spring and autumn, when thaw now persists longer.

University of Colorado Boulder scientists are also collecting deeper cores and expanding laboratory simulations. Federal agencies are supporting infrastructure that allows year-round monitoring of permafrost dynamics.

Tracking Carbon More Precisely

New monitoring strategies combine satellite observations, field sensors, and large-scale data synthesis from hundreds of warming experiments.

These efforts aim to capture abrupt thaw events and underrepresented gases like nitrous oxide, which is far more potent than carbon dioxide. Improved measurements are essential for narrowing uncertainty in future climate projections.

Scientific Debate Continues

Some experts caution against framing permafrost thaw as a single “carbon bomb.” Studies show competing microbial processes and regional variability.

Certain Arctic systems may temporarily absorb more carbon as vegetation expands, while others weaken rapidly. The emerging consensus is that permafrost feedbacks are complex, powerful, and highly uneven.

What the Future Holds

Under current warming trajectories, a majority of near-surface permafrost could disappear by 2100. Limiting warming closer to 1.5°C would preserve significantly more frozen ground.

Whether increased plant growth can offset microbial emissions remains uncertain, particularly as deeper, older carbon becomes increasingly accessible.

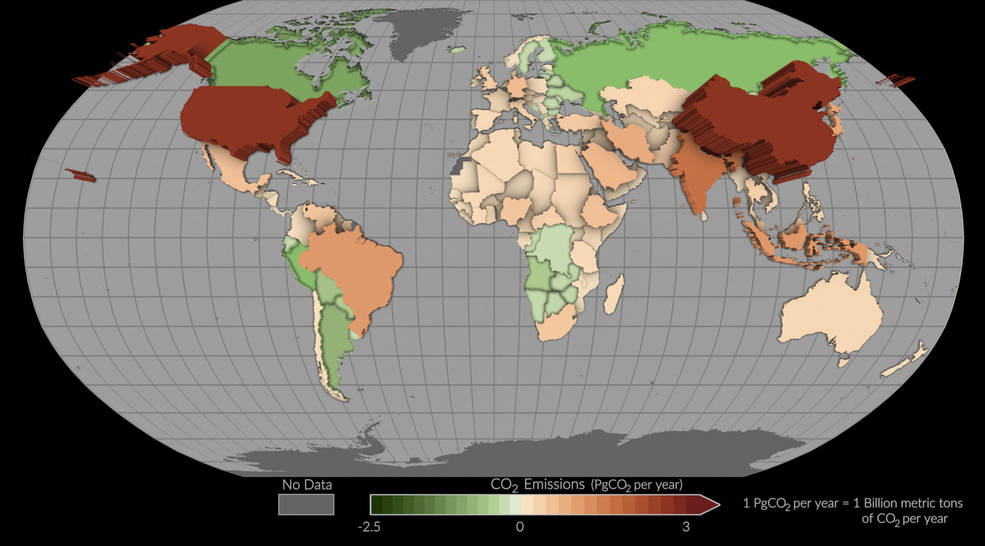

Policy Blind Spots

Most national climate pledges do not explicitly account for permafrost emissions. The UNFCCC has warned that excluding these feedbacks risks overshooting temperature targets.

Emissions from thawing permafrost could rival those of major industrialized nations, complicating efforts to meet global carbon budgets.

Global Climate Ripples

Permafrost thaw is not confined to Alaska. Vast regions of Siberia and high-altitude areas across Asia are also warming and drying.

These changes interact with atmospheric circulation, cloud formation, and precipitation patterns, potentially amplifying climate impacts far beyond the Arctic.

Tipping Points and Abrupt Change

Abrupt thaw features such as thermokarst lakes and wetlands can release greenhouse gases rapidly. As warming intensifies, these nonlinear responses become more likely.

Scientists warn that once certain thresholds are crossed, emissions could accelerate on timescales relevant to human planning and infrastructure.

Cultural and Ethical Dimensions

For Indigenous Arctic communities, permafrost thaw disrupts long-held knowledge of stable landscapes. Villages are forced to adapt or relocate as ground subsides.

The findings also raise ethical questions about how humanity manages landscapes that store ancient life and carbon critical to Earth’s climate balance.

What It Signals Now

The revival of Ice Age microbes underscores that permafrost is not inert. It is a dynamic system capable of amplifying warming long after temperatures rise.

The key warning is not sudden catastrophe, but delayed consequences. What happens underground today may shape the climate decades from now.

Sources:

- NASA Earth Observatory – “40,000-Year-Old Microbes Revived from Alaska Permafrost—Implications for Arctic Carbon Release”

- Live Science, Sept 2025 – “40,000-Year-Old Microbes Revived from Alaska Permafrost—Implications for Arctic Carbon Release”

- Science Advances, 2025 – “40,000-Year-Old Microbes Revived from Alaska Permafrost—Implications for Arctic Carbon Release”

- Nature Climate Change, Jan 2025 – “40,000-Year-Old Microbes Revived from Alaska Permafrost—Implications for Arctic Carbon Release”

- UNFCCC Report, 2025 – “40,000-Year-Old Microbes Revived from Alaska Permafrost—Implications for Arctic Carbon Release”

- The Arctic Institute, 2025 – “40,000-Year-Old Microbes Revived from Alaska Permafrost—Implications for Arctic Carbon Release”