Saturday morning, November 15, 2025, dawned gray and ominous across Southern California. The sky didn’t look like rain—it looked like the sky itself was drowning. Meteorologists were using words they rarely used: catastrophic. An atmospheric river had stalled directly over the region.

By afternoon, what followed would test whether modern emergency systems could handle what climate scientists now call “the new normal” of extreme weather events affecting the state.

The Numbers That Put It in Perspective

At least 23 million Americans under flood alerts or warnings woke that Saturday. The National Weather Service Weather Prediction Center issued a Level 3 out of 4 flash flood threat, their most dire warning.

Text alerts pinged across phones from Ventura County through Malibu, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Ventura, Orange, and San Diego counties. But numbers on a screen can’t capture what residents felt: knowledge that their neighborhood was about to become a disaster zone.

A Month’s Rain Falls in Three Days

Downtown Santa Barbara recorded 8.58 inches. San Marcos Pass captured 13.57 inches in three days—more than ten times the typical November rainfall. Imagine filling a bathtub and pouring it over a square mile in just three days.

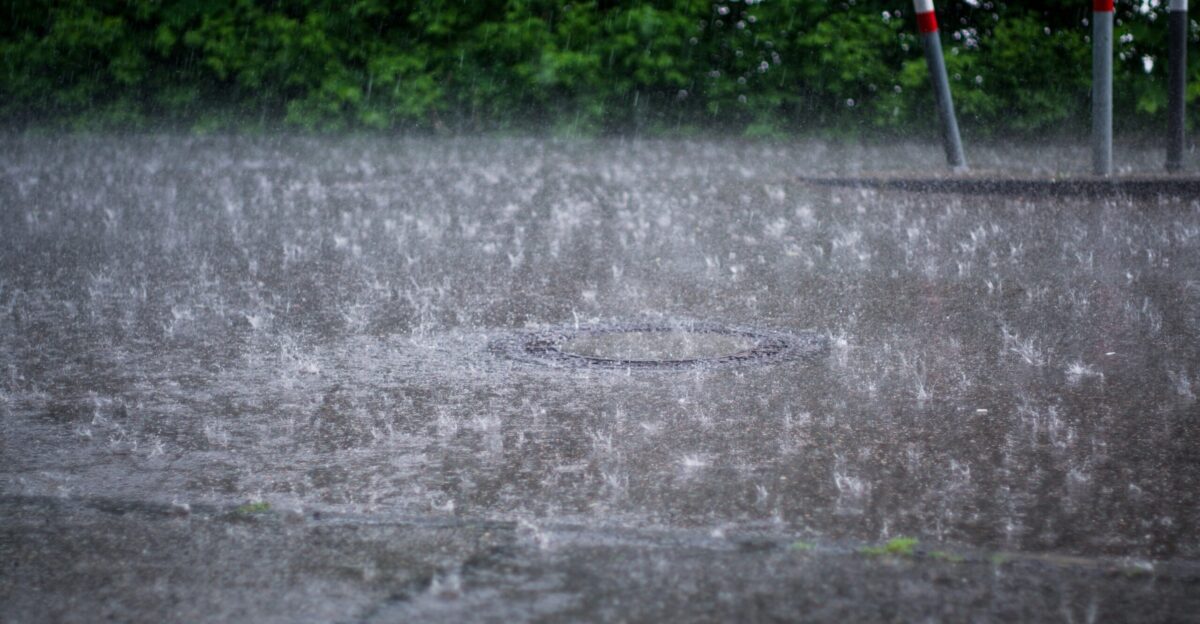

The storm drains couldn’t handle the volume. Water had nowhere to go. Intersections became rivers. The Mission Street underpass in Santa Barbara became severely flooded by Saturday evening.

A Lifeline Disappears

California’s Highway 101 was temporarily shut down in Santa Barbara County as floodwaters inundated roadways and mudslides blocked multiple lanes. For drivers caught on Saturday, the experience was terrifying. A vehicle became stuck in six inches of mud on the northbound side—a preview of worse to come.

Multiple offramps closed as crews scrambled to clear debris. For a region already nervous about burn scars from the 2017 Thomas Fire, this was the nightmare scenario.

Mass Evacuations Echo Historic Precedent

Mandatory evacuation orders were issued for extreme-risk debris flow zones in Santa Barbara County, including communities in Montecito and Carpinteria. Officials issued orders for properties downslope from burn scar areas prone to mudslides and debris flows. The scale of this response echoed the aftermath of the February 2018 mudflow, when approximately 30,000 residents had to evacuate from these same communities.

The 2017 Thomas Fire left burn scars that are still healing, over seven years later—only approximately 20 percent of which have recovered by 2024—creating ongoing vulnerability to debris flows during heavy rainfall.

Why Burn Scars Turn Into Kill Zones

Emergency officials spent months installing K-rail barriers and positioning response teams for this exact moment. But here’s what most people don’t understand about fire scars: they’re not just reminders—they’re geological disasters waiting to happen. Fire-denuded hillsides have no vegetation to absorb water or slow runoff.

Once rain began, residents in downslope communities faced imminent danger as walls of mud and boulders could rapidly flow down denuded hillsides. Communities like Montecito were on borrowed time.

Downtown Becomes a Raging River

Saturday at 8 p.m., downtown Santa Barbara experienced something residents had never seen before. City officials later called it “State River”—State Street transformed into a fast-moving waterway. Intersections of Sola, Cota, Salsipuedes, and Laguna Street flooded in minutes as runoff overwhelmed storm drains designed decades ago.

One woman was rescued from her car. Several drivers abandoned their vehicles and ran for higher ground.

Emergency Services Overwhelmed

Emergency personnel responded to a stunning 50 percent surge in calls for help as vehicles stalled and residents became trapped in submerged areas. The LA Fire Department deployed additional personnel across the city to respond to debris flows and widespread flooding.

Jackie Ruiz, Santa Barbara County’s emergency coordinator, confirmed “minor rock slides and debris slides into roadways”. Despite months of preparation, every first responder was overwhelmed by the sheer volume of emergencies.

When a Family’s Beach Day Turned Tragic

On Friday, November 14, Yuji Hu of Calgary and his family were swept by tragedy at Garrapata State Beach. When powerful waves pulled his seven-year-old daughter Anzi into the ocean, Yuji bravely entered the water to save her.

Despite a rescue effort and immediate CPR from an off-duty State Parks officer, Yuji lost his life, leaving behind a profound sense of loss for his loved ones and all touched by their story.

A Desperate Search

The mother was rescued with mild hypothermia; a 2-year-old sibling remained safe on the beach. But Anzi had vanished into the Pacific. For two days, Monterey County Sheriff’s Office, California State Parks, CalFire, and the U.S. Coast Guard searched with helicopters overhead and divers in cold Pacific waters.

Families worldwide watched the search unfold on social media, hearts aching for a child lost to nature. On Sunday at 1:20 p.m., a volunteer diver located the girl’s body, bringing closure.

The Death Toll Mounts

By Sunday evening, six confirmed deaths had been attributed to the atmospheric river system. Arnold Jee, a 71-year-old man in Sutter County, died when his vehicle was swept off Pleasant Grove Creek Bridge, submerging his Mazda CX-5. Off the coast, a wooden panga boat capsized in stormy seas near Imperial Beach, claiming four migrant lives.

The U.S. Coast Guard found four deceased and four hospitalized survivors. Each death represented a family shattered by forces no one could control.

When Records Fall Across the Region

November rainfall records shattered with almost poetic finality. Downtown Los Angeles broke a seventy-three-year-old Saturday record with 1.65 inches on November 15. Oxnard obliterated the 1934 record with 3.18 inches on Saturday alone. Santa Barbara Airport recorded 2.9 inches, shattering the 1952 record.

These weren’t abstract statistics; they represented the most intense precipitation in nearly a century, reshaping how experts talk about climate in California.

What Meteorologists Are Saying

Meteorologist Rose Schoenfeld of the National Weather Service explained that the worst had passed, but the danger remained elevated. “We still have gusty winds, knocked down trees, and scattered showers,” she noted Saturday evening as conditions persisted. But there was more bad news. Additional storm systems were approaching through Thursday.

Wednesday offered a brief reprieve, but more rain was expected to arrive on Thursday evening. Soil was at maximum capacity—any additional rainfall would trigger secondary mudslides.

The Climate Connection Nobody Wants to Talk About

The November 2025 atmospheric river highlighted what California’s leaders have grappled with for years: climate patterns are undergoing fundamental shifts. These extreme precipitation events now occur outside traditional winter windows. Meteorologist Bryan Lewis explained the system “was allowed to spin right off the coast” before hitting the mountains, enhancing rainfall.

Research shows that while atmospheric rivers currently generate approximately $1 billion annually in Western U.S. flooding damages, comparable atmospheric river sequences in 2023 caused preliminary damages exceeding $3 billion, and a severe 2024 atmospheric river event caused damages estimated between $9 billion and $ 11 billion.

Preliminary Damage Assessments Point to Significant Losses

As of November 18, 2025, official storm damage assessments were ongoing, but reports already signaled severe impacts across California. In recent years, atmospheric river events have resulted in costs exceeding $3 billion, with a single February 2024 storm potentially causing up to $11 billion.

Early indications suggest November’s damages could be similarly significant, with widespread flooding, infrastructure losses, and agricultural damage.

The Cruelty of Double Disaster in Seven Years

For Montecito and Carpinteria residents, the 2025 atmospheric river was a stark reminder of enduring vulnerability. The 2017 Thomas Fire left scars still healing, and its aftermath—especially the deadly 2018 mudflow that claimed over 20 lives—remains vivid.

Facing two devastating water disasters in seven years, many families felt more than just loss; for some, the trauma was so profound they chose to relocate, unable to face another round of uncertainty and fear.

The Reckoning Begins

Federal disaster declarations were expected to trigger the release of relief funds and coordinate recovery efforts across counties and agencies. Emergency officials would conduct thorough after-action reviews to understand what worked and what failed. The conversation among climate scientists is shifting from “if this happens again” to “when this happens again”.

California must fundamentally rethink infrastructure, zoning, and evacuation protocols. November 2025 has become a case study in climate adaptation.

Infrastructure Under Pressure

The storm exposed fragility in systems built for a different era. Storm drains designed fifty years ago couldn’t handle twenty-first-century precipitation rates. Highway 101, with single-point failure, became a liability when flooding forced closures. Power lines went down across counties, leaving thousands without electricity for days.

Water service was disrupted in several areas due to damage to pipes caused by flooding. Rebuilding isn’t just replacement—it’s redesigning for a fundamentally changing climate.

The Human Stories Behind Every Number

Behind every statistic is a person or family. The thousands evacuated represent thousands of different decisions: what to pack, where to go, whether to leave pets behind. The six deaths represent six families learning the worst possible news.

The 23 million under alerts represent millions of hours of anxiety and fear. These numbers only mean something when translated back into human experience and lived reality.

Looking Back, Planning Ahead

November 2025 will be remembered as a turning point—not because it was the worst California experienced, but because it highlighted the ongoing vulnerability of fire-scarred communities to the impacts of atmospheric rivers.

It exposed vulnerabilities. It revealed how interconnected modern emergencies have become. And it forced a difficult conversation: How do we live in a state where weather itself has become the primary hazard?

Recovery and Resilience: The Long Road

For Anzi Hu’s family in Canada, no recovery restores what was lost in those moments. For migrants’ families across borders, for Arnold Jee’s loved ones, and for communities still processing the cumulative trauma of fire vulnerability and atmospheric river hazards, 2025 dealt California challenging circumstances.

Infrastructure repair bills will mount for months. Recovery will take years. But most important will be psychological recovery—helping communities process disaster cycles and reimagine resilience in an era of atmospheric rivers.