The identification of Epiaceratherium itjilik from Canada’s High Arctic represents a major advance in understanding ancient mammal distribution and Arctic climate history. Recovered from Haughton Crater on Devon Island, Nunavut, the roughly 23-million-year-old rhinoceros is known from about 75% of its skeleton—an exceptional level of completeness.

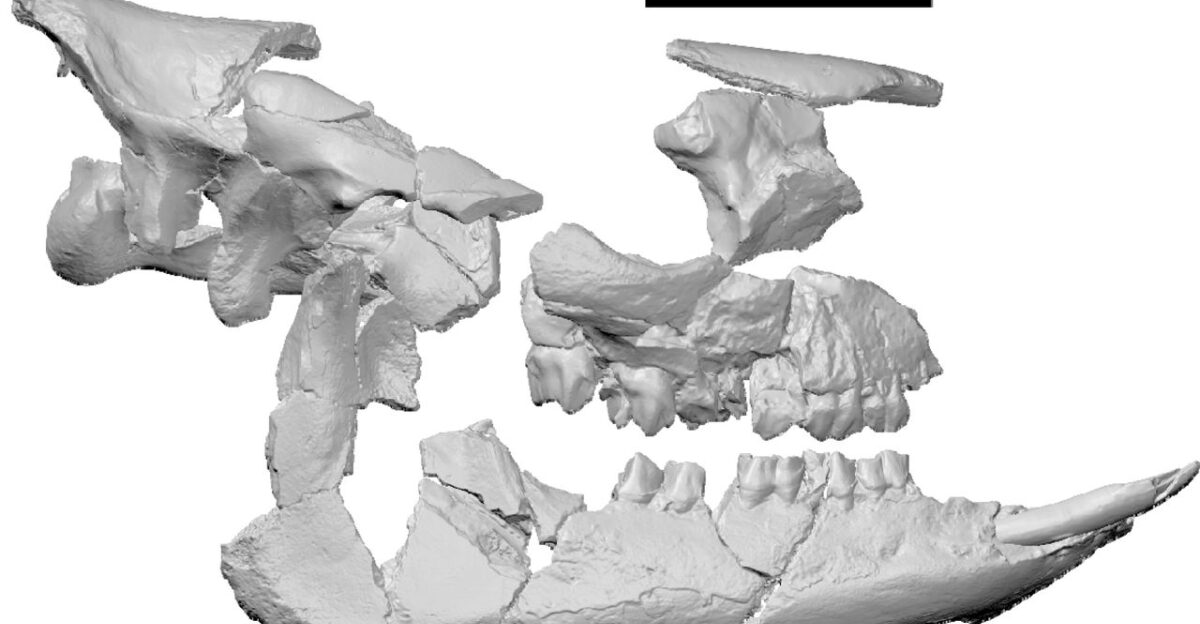

The fossil’s three-dimensional preservation allows unusually detailed study and establishes it as the northernmost rhinoceros species ever documented, fundamentally revising assumptions about Early Miocene Arctic ecosystems.

The Haughton Crater — A Geological Archive of Deep Time

Haughton Crater, a 23-kilometer-wide impact structure on Devon Island, provides the geological setting that preserved the Arctic rhino. Formed approximately 31–32 million years ago, the crater later hosted a lake during the Early Miocene.

Fine-grained sediments accumulated in this basin, creating low-oxygen conditions ideal for fossil preservation. Over millions of years, these deposits protected the rhino’s remains, allowing paleontologists to recover a uniquely intact window into Arctic life during a much warmer period.

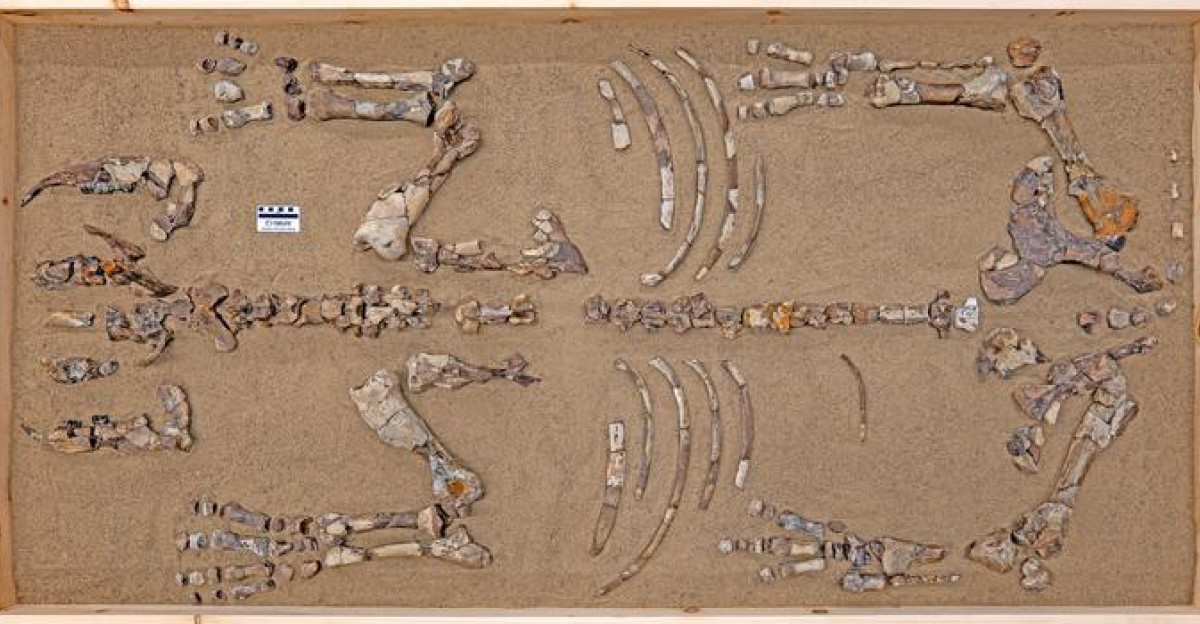

Why 75% Skeletal Completeness Is Extraordinary

In paleontology, most species are known from isolated bones or fragments, limiting how confidently scientists can interpret anatomy and behavior. Recovering roughly 75% of E. itjilik’s skeleton dramatically changes that equation.

The specimen includes much of the skull, teeth, vertebrae, and limb bones, enabling accurate reconstructions of body proportions and movement. This level of completeness reduces speculation and allows researchers to place the species more securely within rhinocerotid evolution and Arctic ecological history.

Naming Epiaceratherium itjilik — Science and Cultural Respect

The species name Epiaceratherium itjilik reflects both evolutionary classification and cultural collaboration. The genus Epiaceratherium includes small, hornless early rhinoceroses known primarily from Eurasia.

The species epithet “itjilik,” meaning “frosty” in Inuktitut, was chosen in consultation with Inuit representatives, including an Elder from Grise Fiord. This approach acknowledges Indigenous language and presence in the Arctic while formally recognizing a species that once lived on Inuit homelands.

A Warm Arctic — Rethinking Miocene Climate

The presence of a rhinoceros in the High Arctic confirms that Devon Island once supported a much warmer environment. During the Early Miocene, the region hosted forested landscapes rather than ice-dominated deserts.

Paleobotanical and sedimentary evidence indicates conditions consistent with boreal or cool-temperate forests, capable of sustaining large herbivores. These findings force revisions to climate models and show that polar regions experienced dramatic natural warmth long before human-driven climate change.

An Ecosystem with Land and Water Mammals

The Arctic rhino did not live in isolation. Fossils from the Haughton region also include Puijila darwini, an otter-like mammal representing an early stage in seal evolution. Together, these species indicate a diverse ecosystem with forests, freshwater bodies, and complex food webs.

The coexistence of terrestrial herbivores and semi-aquatic carnivores shows that Early Miocene Arctic environments supported rich and varied mammalian communities unlike anything seen there today.

Ancient Proteins — A Molecular Breakthrough

In 2025, scientists successfully extracted and sequenced enamel proteins from an Early Miocene Arctic rhinoceros tooth closely related to E. itjilik. Dating to roughly 21–24 million years ago, these proteins represent the oldest mammalian proteome ever recovered.

Unlike DNA, which degrades rapidly, proteins can persist far longer under stable conditions. This discovery extends the molecular record deep into geological time and provides new tools for reconstructing mammal evolution.

Evolutionary Timing and Rhino Lineages

Analysis of the recovered proteins allowed researchers to estimate when Arctic rhinos diverged from other rhinocerotid lineages. Results suggest that the Epiaceratherium lineage split from other rhinos between approximately 41 and 25 million years ago.

These findings align with anatomical evidence linking the Arctic species to earlier European relatives. Together, fossil morphology and molecular data provide a clearer timeline for how early rhinos diversified and spread across continents.

Size, Shape, and Lifestyle

Epiaceratherium itjilik was a small, hornless rhinoceros, far smaller than modern rhino species. Estimates suggest it was closer in size to a large dog or sheep rather than today’s massive African or Asian rhinos. Its limb bones indicate a sturdy but agile animal adapted for moving through forested terrain.

Dental features show it was a browser, feeding on leaves and soft vegetation rather than grasses, consistent with a wooded Arctic habitat.

How the Fossil Was Preserved

The rhino’s remarkable preservation reflects a combination of rapid burial and stable environmental conditions. After death, the animal’s remains settled into fine lake sediments within Haughton Crater, limiting scavenging and decay.

Over time, the bones underwent only partial mineral replacement, preserving their three-dimensional structure. Later freeze–thaw cycles associated with permafrost gently shifted some material upward, aiding modern recovery without destroying the fossil’s integrity.

Teeth as Records of Ancient Diets

The teeth of E. itjilik offer direct evidence of how it lived. Its molars show complex ridges designed for grinding fibrous plant material, confirming a browsing diet.

Ongoing and future studies of tooth enamel chemistry may further reveal what types of plants dominated Devon Island’s forests. Such analyses transform teeth into chemical archives, preserving information about vegetation, climate, and seasonal conditions millions of years ago.

Extinction Without Humans

Epiaceratherium itjilik eventually disappeared as Arctic environments continued to change. Shifts in climate, vegetation, and animal communities over millions of years likely reduced suitable habitat. Its extinction highlights how species can vanish through natural environmental transitions, long before human influence.

Studying these deep-time losses helps scientists understand extinction as a natural process while providing context for today’s accelerated, human-driven biodiversity crisis.

Placing the Arctic Rhino Among Its Relatives

More than 50 rhinocerotid species are known from the fossil record, with only five surviving today. Within this broader family, E. itjilik stands out for its latitude and preservation.

Most fossil rhinos are found at lower latitudes, making this Arctic species critical for understanding how adaptable early rhinos were. Comparisons with European Epiaceratherium species show shared traits and reveal how one lineage adapted to extreme northern environments.

Permafrost as a Preservation Ally

Modern Arctic permafrost plays a key role in protecting ancient fossils. Cold, stable ground slows chemical breakdown and physical erosion, preserving remains over immense spans of time. At Haughton Crater, permafrost processes helped keep Miocene sediments intact and accessible.

As Arctic landscapes continue to erode and thaw, they are revealing valuable records of past life—while also underscoring the urgency of documenting them before degradation accelerates.

Rhino Evolution as a Success Story

Rhinoceroses were once among the most widespread large mammals on Earth, occupying habitats across Africa, Eurasia, and North America. Epiaceratherium itjilik represents this evolutionary success during a period of experimentation and diversification.

Hornless, small-bodied species like it show that rhino evolution was not limited to massive grazers. Today’s five surviving species are the last remnants of a once far more varied and adaptable family.

Modern Tools Unlocking Ancient Lives

The Arctic rhino was understood through a combination of traditional fieldwork and advanced analytical methods. CT scanning and digital modeling allow researchers to examine fragile bones without damaging them.

Phylogenetic techniques integrate fossil and molecular data, while paleoproteomics extracts evolutionary signals from ancient proteins. Together, these approaches reveal anatomy, relationships, and timelines that would have been impossible to reconstruct just a few decades ago.

Lessons for Today’s Climate Conversation

The existence of a forested Arctic with rhinoceroses provides perspective on Earth’s natural climate variability.

However, the transition from that warm Miocene world to today’s frozen Arctic occurred over millions of years. Modern climate change is unfolding far faster. This contrast highlights a critical risk: many species may not adapt quickly enough to the pace of current environmental change, even though the planet has experienced dramatic shifts before.

Hidden Fossil Potential in the Arctic

The discovery of E. itjilik shows that even well-known Arctic sites still hold surprises. Vast areas of the High Arctic remain underexplored compared to fossil-rich regions farther south. Advances in mapping, remote sensing, and stratigraphic analysis are helping scientists identify new fossil exposures.

These tools suggest that additional undiscovered species may await beneath Arctic sediments, offering further insight into ancient polar ecosystems.

Beyond Paleontology — Broader Scientific Impact

The Arctic rhino informs multiple scientific fields. Biogeographers gain evidence that mammals dispersed across high-latitude land connections later than once assumed.

Paleoclimatologists obtain concrete data for modeling Early Miocene Arctic warmth. The species’ Inuktitut name reflects growing collaboration between scientists and Indigenous communities. Together, these elements show how a single fossil discovery can reshape understanding across disciplines.

A Fossil That Changed the Map

Epiaceratherium itjilik reshapes what scientists know about Arctic life, climate, and mammal evolution. Its 75% complete skeleton enables rare anatomical clarity, while associated protein discoveries push molecular research deep into the Miocene.

The fossil proves that the High Arctic once supported forests and large mammals, challenging long-held assumptions about polar environments. As Arctic research expands, discoveries like this will continue redefining Earth’s deep-time story.

Sources:

- “Discovery of an extinct rhino from Canada’s High Arctic” – Canadian Museum of Nature (news release)

- “Rhinos Lived in High Arctic 23 Million Years Ago” – Sci.News

- “Ancient rhino teeth unlock 20-million-year-old secrets in Canada” – ArcticToday

- “Rhino discovery shows Arctic ‘big centre’ for mammal evolution, researchers say” – Nunatsiaq News

- “Hornless rhino roamed Canadian High Arctic 23 million years ago” – Reuters (via multiple outlets)

- “Scientists Discover a 23-Million-Year-Old ‘Arctic Rhino’ in Canada” – SciTechDaily