For decades, many models of marine evolution assumed most animal diversity originated in shallow, sunlit seas and only later expanded into deeper environments. Fossils from Middle Jurassic sediments in the Austrian Alps complicate that picture.

Roughly 70 species of marine invertebrates—many resembling modern deep-sea groups—were recovered from deposits interpreted as deep-marine in origin and dated to about 180 million years ago. Several lineages appear earlier here than in known shallow-water records, suggesting that deep marine settings were not merely late recipients of biodiversity, but active evolutionary environments much earlier than traditionally assumed.

Why These Fossils Were Unexpected

Deep-marine environments are generally considered poor candidates for fossil preservation. Low sedimentation rates, biological disturbance, and chemical dissolution all reduce the likelihood that organisms will be buried and preserved. As a result, the deep sea has long appeared nearly absent from the early fossil record.

The Austrian assemblage contradicts that expectation. The fossils occur in sediments interpreted as deposited far below the reach of sunlight, and they preserve a surprisingly diverse community. Their existence highlights how preservation bias, rather than true absence of life, has shaped perceptions of ancient deep-marine ecosystems.

Evidence for a Deep-Marine Setting

Researchers did not rely on a single indicator to identify the environment. The fossil assemblage lacks corals, algae, and other organisms that depend on sunlight, while being dominated by echinoderms and mollusks typical of modern deep-water communities. Sedimentological features—including fine-grained deposits and structures consistent with deep-marine accumulation—match what is seen in present-day bathyal and abyssal settings.

Together, biological composition and geological context independently support the interpretation that these organisms lived in a deep-marine environment rather than on a shallow shelf.

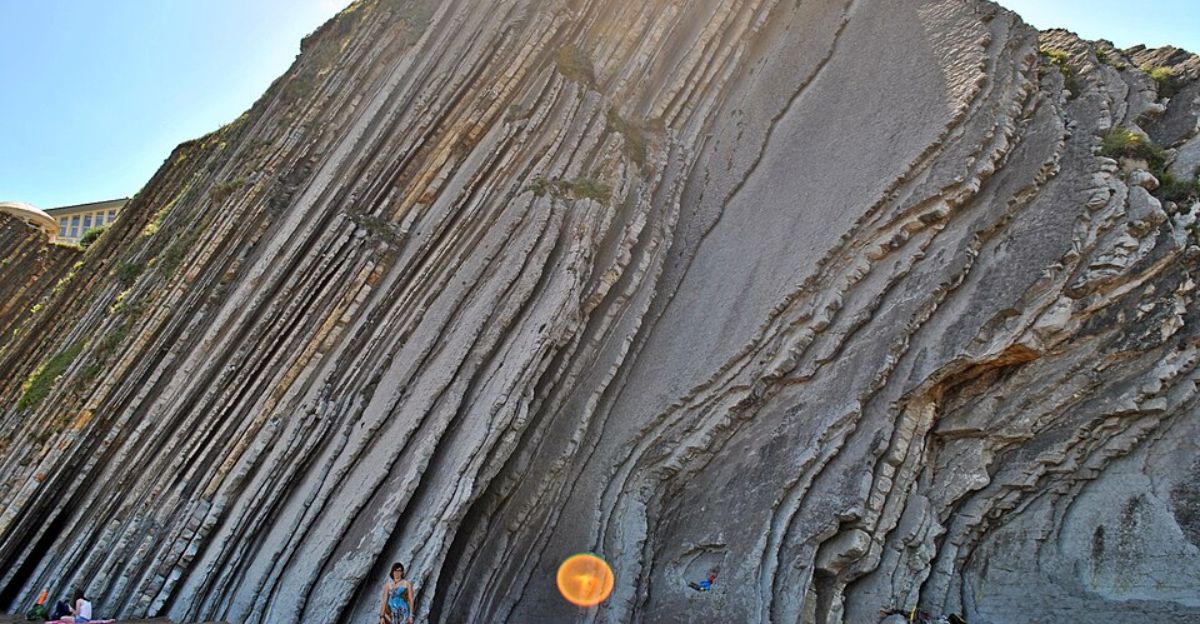

The Alpine Record: Deep Seafloor Raised to the Surface

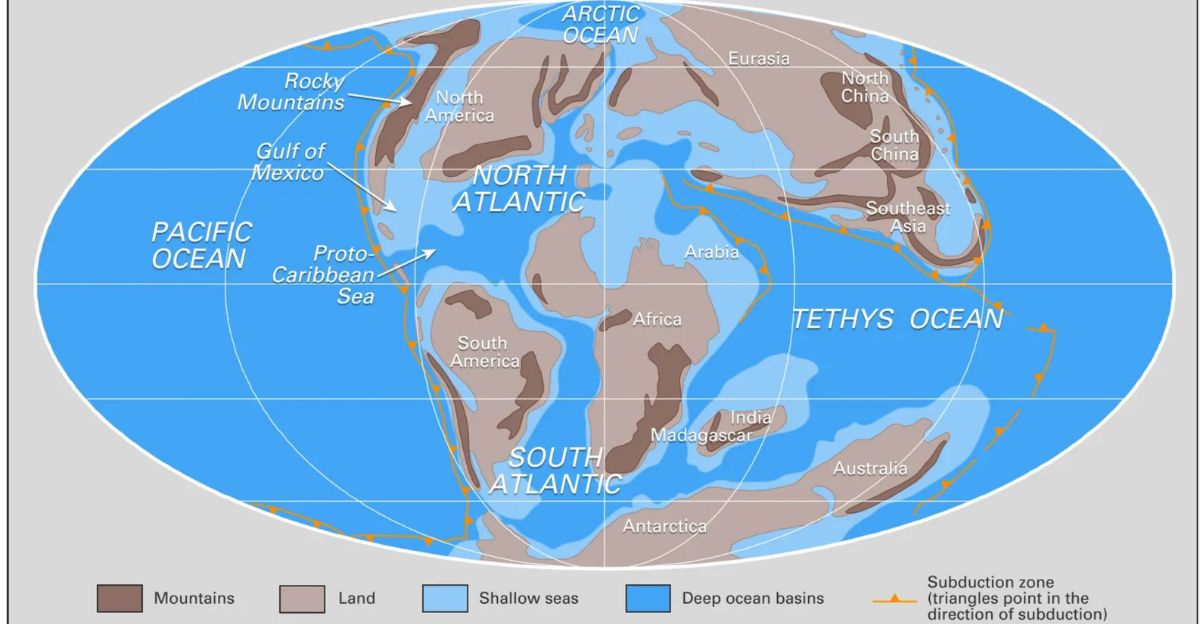

The fossils were found near Salzburg, Austria, in Jurassic sediments originally deposited on the floor of the Tethys Ocean. Subsequent plate tectonics during Alpine mountain building uplifted these rocks thousands of meters above sea level. A landslide exposed fossil-rich layers, allowing long-term collection and study.

This geological history is critical: it provides rare access to ancient deep-marine deposits without drilling or submersibles. What appears today as a mountain landscape once lay beneath a deep ocean, preserving an otherwise inaccessible chapter of marine life.

The Prevailing Shallow-Origin Assumption

Before these findings, the oldest fossils of many modern deep-sea groups were known only from much younger, often shallow-water deposits—typically younger than about 100 million years. This pattern reinforced the idea that deep-sea faunas arose later, after adapting from shallow ancestors.

Because older deep-marine fossils were scarce, the deep ocean was often treated as evolutionarily secondary. The Jurassic Austrian assemblage challenges that assumption by showing that several lineages existed in deep settings tens of millions of years earlier than their shallow-water fossil records indicate.

Energy Sources Beyond Sunlight

Life in deep water does not depend solely on sunlight. In modern oceans, chemosynthetic microbes use chemical energy—often linked to sulfur or methane—to fuel ecosystems independent of photosynthesis. Jurassic deep-marine environments likely combined multiple energy sources, including sinking organic matter from surface waters and localized chemosynthetic production.

The structure of the Austrian fossil community, dominated by suspension feeders and detritivores, is consistent with a sustained supply of organic material, supporting the view that deep-marine ecosystems were energetically viable long before the modern ocean formed.

How Deep-Marine Fossilization Can Occur

Although rare, fossilization in deep water is possible under specific conditions. Rapid burial by sediment gravity flows, reduced oxygen levels that slow decay, and limited disturbance by burrowing organisms can all enhance preservation.

Episodic events, rather than continuous sedimentation, are especially important. In deep-marine settings, turbidity currents can quickly bury organisms, protecting skeletal material long enough for mineralization. These processes help explain how diverse deep-water communities could occasionally enter the fossil record despite generally unfavorable conditions.

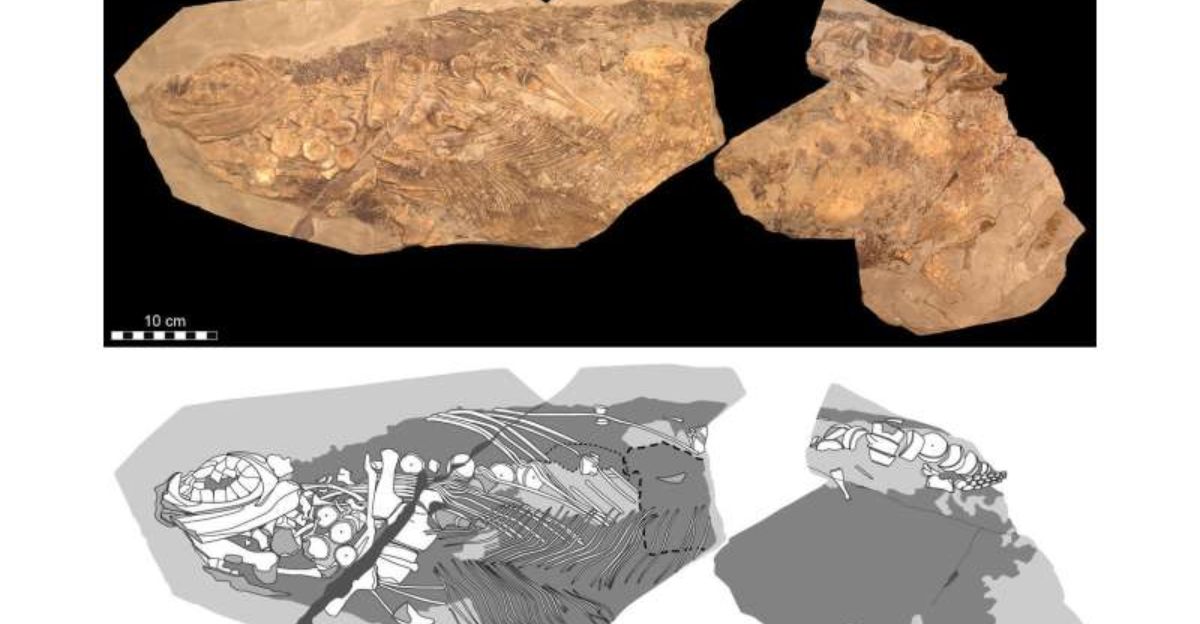

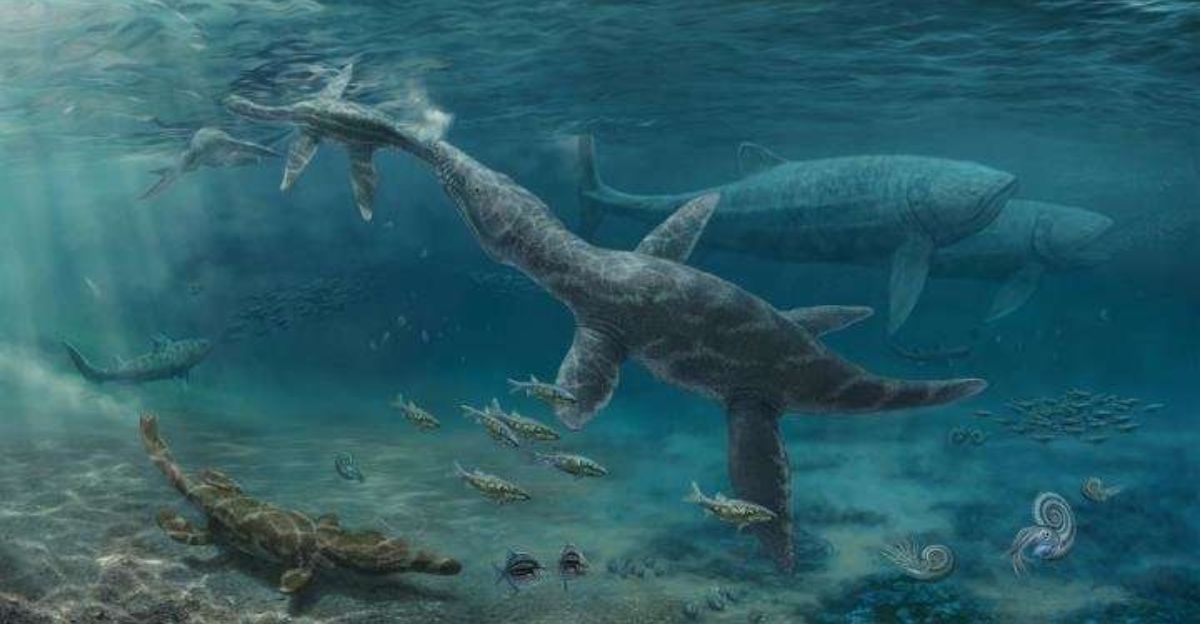

Jurassic Marine Food Webs Were Robust

Large marine reptiles from the same period provide context for ecosystem complexity. Jurassic ichthyosaurs, including specimens exceeding 10 meters in length, indicate abundant prey and well-structured food webs.

While these predators did not necessarily inhabit the deepest environments continuously, their presence reflects productive oceans overall. When combined with evidence of diverse deep-marine invertebrate communities, the broader picture is of Jurassic seas that supported complex, interconnected ecosystems across a wide range of depths, rather than a biologically impoverished deep ocean.

Comparing Deep and Shallow Diversity

When researchers compared the Austrian deep-marine fossils with coeval shallow-water assemblages, they found that several deep-water lineages appear earlier in time. This does not imply that shallow seas lacked diversity, but it does suggest that evolutionary innovation was not confined to coastal environments.

The deep sea may have served as a long-term reservoir for lineages, buffering them from extinction events more common in dynamic shallow habitats. Such a role aligns with patterns observed in the modern ocean.

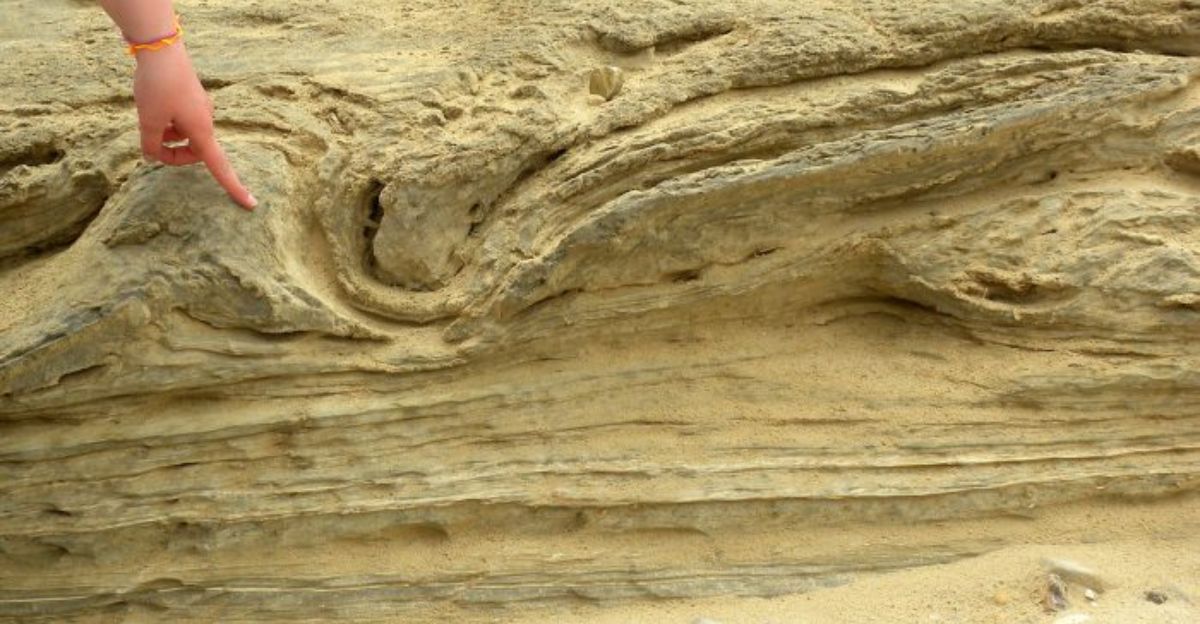

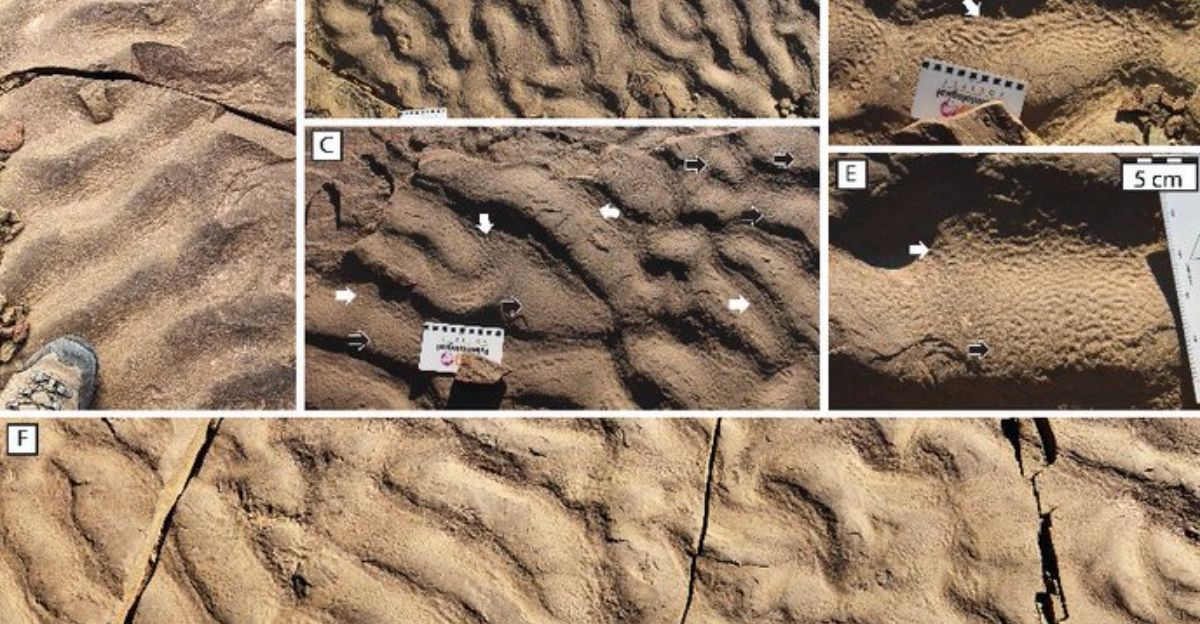

Morocco’s Wrinkle Structures: Life Without Light

Jurassic turbidite deposits in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains contain small wrinkle-like sedimentary structures long associated with microbial mats. Detailed analysis showed these sediments were deposited well below the photic zone, ruling out photosynthesis as the energy source.

Elevated carbon beneath the structures supports a microbial origin, and modern deep-water analogues confirm that chemosynthetic microbes can form similar textures today. This discovery provides the first documented evidence that such wrinkle structures can form through chemosynthesis, expanding where scientists can look for ancient microbial life.

Oxygen Conditions in Jurassic Deep Waters

Deep water is often assumed to be oxygen-poor, but oxygen distribution has varied widely through geological time. Evidence from Jurassic sediments indicates that some deep-marine basins were sufficiently oxygenated to support mobile, aerobic animals, including echinoderms.

At the same time, localized low-oxygen conditions aided preservation by limiting decay. The coexistence of oxygen-dependent life and good fossil preservation reflects spatial and temporal variability, rather than uniformly inhospitable deep-sea conditions.

Turbidity Currents as Preservation Agents

Turbidity currents—fast-moving, sediment-laden flows—play a central role in preserving deep-marine life. In Morocco, microbial mats formed during quiet intervals and were later buried by incoming turbidites, sealing their textures into the rock record. Similar processes likely operated in the Tethys Ocean, periodically entombing benthic communities.

These events create snapshots of ancient ecosystems, preserving delicate features that would otherwise be erased. Far from preventing fossilization, episodic disturbance was often the key to it.

Why the Age Is Secure

The Austrian fossils occur in well-studied Middle Jurassic strata dated using ammonite biostratigraphy, a globally calibrated method. The Moroccan wrinkle structures are found in Jurassic turbidites whose age is constrained by regional stratigraphy and peer-reviewed analysis.

Multiple independent dating approaches converge on an age of roughly 180 million years. These are not isolated finds but components of coherent geological sequences, making significant age revision unlikely.

Rethinking Evolutionary Direction

If deep-marine fossils predate shallow-water representatives of the same groups, then shallow species cannot always be ancestral. Instead, some lineages may have originated or diversified in deeper settings before expanding into shallower habitats.

This does not overturn all existing models but requires greater flexibility in how evolutionary pathways are interpreted. Marine evolution appears more dynamic and multidirectional than once assumed.

Structured Ecosystems in Deep Water

The Austrian assemblage includes organisms occupying multiple ecological roles—filter feeders, grazers, predators, and scavengers—indicating a structured ecosystem rather than marginal survival.

Combined with evidence of microbial primary production from Morocco, this supports the existence of complete food webs in dark, deep-marine environments.

Such systems require stability and sustained energy input, reinforcing the idea that deep seas were long-term ecological arenas, not temporary refuges.

Jurassic Oceans Were Not Modern Oceans

Jurassic ocean circulation differed markedly from today’s. Warmer global temperatures, different continental arrangements, and the absence of permanent polar ice caps altered mixing and oxygenation.

The Tethys Ocean, in particular, was a vast, complex seaway with unique physical conditions. Applying modern deep-ocean assumptions directly to Jurassic environments oversimplifies a system that was fundamentally different in structure and behavior.

Rarity Does Not Mean Impossibility

Deep-marine fossilization is unlikely on a per-organism basis, but over millions of years, rare events accumulate. Vast populations, episodic burial, and tectonic uplift together make eventual discovery statistically inevitable.

The Austrian and Moroccan sites represent the small fraction of deep-marine history that survived every filter. Their rarity reflects geological probability, not biological absence.

Broader Scientific Implications

Recognizing deep-marine environments as long-standing centers of biodiversity affects multiple fields. Evolutionary models must incorporate deeper habitats more fully. Conservation debates gain urgency as deep-sea ecosystems are increasingly disturbed.

Astrobiology also benefits: chemosynthetic systems operating without sunlight strengthen arguments that life could exist in subsurface oceans on icy moons, independent of surface conditions.

The Next Phase of Research

Many uplifted deep-marine sequences worldwide remain understudied. With modern analytical tools—high-resolution imaging, geochemistry, and refined stratigraphy—scientists can systematically search for additional ancient deep-marine communities.

As funding and interest grow, more discoveries are likely to test and refine emerging models of marine evolution.

The Deep Sea Reconsidered

The combined evidence from Jurassic deep-marine fossils in Austria and chemosynthetic microbial structures in Morocco shows that deep oceans hosted diverse, structured ecosystems far earlier than once believed.

Rather than being evolutionary latecomers, deep-marine environments were active participants in the history of life. The idea that biodiversity began shallow and only later descended now appears incomplete. The deep sea was never merely an afterthought—it was part of the main story.

Sources:

“Fossil discovery in Alps challenges theory that all deep sea animals evolved from shallow water ancestors” – Phys Org

“Jurassic Fossils Suggest Deep-Sea Origins of Marine Life” – Scientific American.

“New fossils suggest ancient origins of modern-day deep-sea animals” – EurekAlert!

“GSA News Release 26-02: Deep-water sediment layers reveal rare microbial wrinkle structures formed far from sunlight” – Geological Society of America news release about Martindale’s work in Morocco.

“Chemosynthetic microbial communities formed wrinkle structures in deep-water turbidites” (exact title varies slightly by citation) – research article by R.C. Martindale et al. in Geology (GSA journal).

“Signs of ancient life turn up in an unexpected place” – Phys.org / GSA-linked news PDF about the same Moroccan wrinkle structures.

“Rutland ichthyosaur fossil is largest found in UK” – BBC News.