Over the past 150 years, the world has experienced an extraordinary rise in animal extinctions, largely as a result of human activities.

Current scientific estimates suggest that the extinction rates today are 100 to 1,000 times higher than the natural background rates, leading many experts to refer to this phenomenon as the sixth mass extinction.

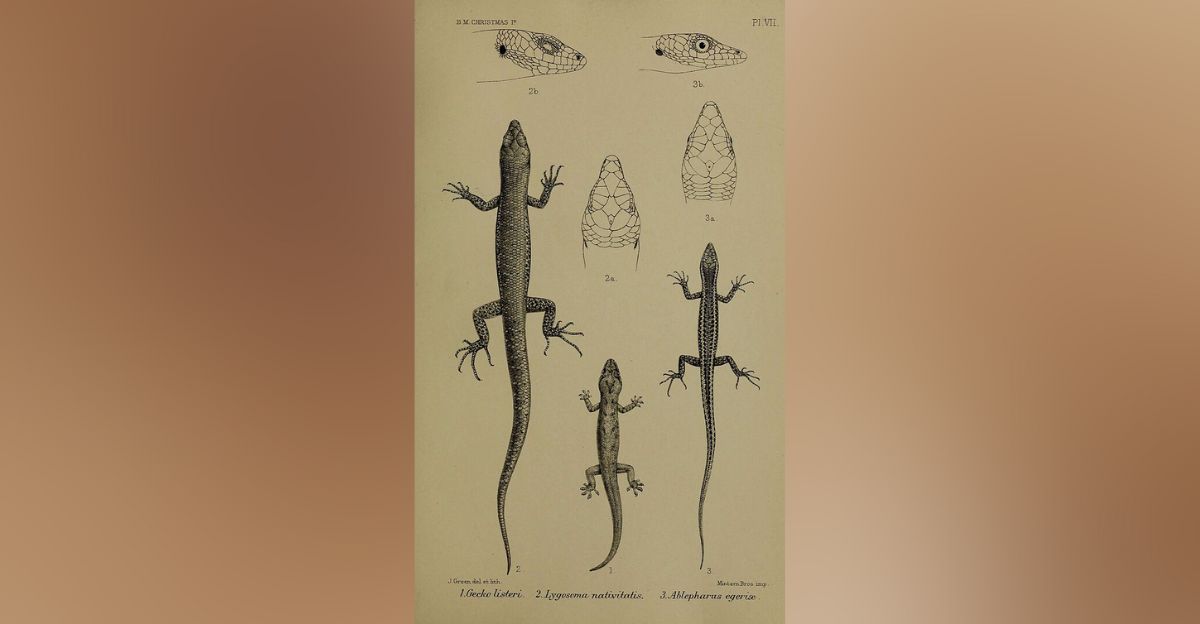

Christmas Island Forest Skink (2014)

The Christmas Island Forest Skink, a unique Australian reptile, became extinct when the last known captive individual, “Gump,” died on May 31, 2014. The IUCN officially declared the species extinct in 2017 after extensive surveys found no survivors.

Once common in Christmas Island’s forests, its population declined by 98% during the 1990s and 2000s due to invasive yellow crazy ants, feral cats, and habitat destruction. Despite conservation efforts, including captive breeding, only three females were captured, underscoring the difficulties in saving this distinctive species.

Bramble Cay Melomys (2015)

The Bramble Cay Melomys, a small rodent from a coral cay near Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, is the first mammal declared extinct due to human-induced climate change.

Rising sea levels and storm surges destroyed its habitat and food sources, with the last confirmed sighting in 2009. This extinction represents a significant milestone, being the first recorded mammalian extinction linked to climate change.

Yangtze River Dolphin (2006)

The baiji, or Yangtze River dolphin, was declared functionally extinct in 2006 after researchers found no specimens during a 2,000-mile survey of the Yangtze River. The last confirmed sighting occurred in 2002.

Recognized by the Whale and Dolphin Conservation group as the first dolphin species driven to extinction by human actions, the baiji’s decline was caused by overfishing, pollution, boat traffic, and dam construction in China’s busiest waterway.

Western Black Rhinoceros (2011)

The Western Black Rhinoceros was declared extinct by the IUCN in 2011, following a 2006 survey that found no surviving individuals in Cameroon.

Once abundant in sub-Saharan Africa, their population declined from hundreds in 1980 to just five by 2001 due to extensive poaching for their horns. The lack of sightings during the 2006 survey confirmed the fears of their complete disappearance.

Northern White Rhinoceros (2018)

The Northern White Rhinoceros is functionally extinct, with the last male, Sudan, dying in March 2018 at Kenya’s Ol Pejeta Conservancy. Only two females remain, both unable to reproduce naturally.

Conservationists note that Sudan’s death marks the loss of an entire subspecies. Scientists are attempting de-extinction through in vitro fertilization using preserved genetic material, but success remains uncertain as the species faces imminent extinction.

Spix’s Macaw (2000)

The Spix’s Macaw, or “Little Blue Macaw,” became extinct in the wild in 2000, with only 60 to 80 individuals left in captivity. This Brazilian parrot has been threatened by habitat destruction and the illegal pet trade.

In 2022, reintroduction efforts began, providing hope for the species’ return to the wild. However, its survival depends on continued human intervention, highlighting the challenges and potential for conservation success.

Golden Toad (1994)

The Golden Toad of Costa Rica, recognized for its bright orange color, was last seen in 1989 in the Monteverde cloud forests and was declared extinct in 1994. Its disappearance was primarily due to chytrid fungal disease and climate change.

Scientists highlight that pollution, global warming, and the deadly chytrid infection formed a “perfect storm” for extinction. The toad’s limited habitat and small population made it especially vulnerable to environmental changes driven by human activities.

Thylacine (1936)

The Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger, was a marsupial predator that went extinct in 1936, with the last known captive individual dying at Hobart Zoo. Although called a “tiger” due to its stripes, it is more closely related to kangaroos.

The main factors in its extinction were competition with dingoes and extensive human hunting, which led to its disappearance from mainland Australia and Tasmania. Despite ongoing reported sightings, no confirmed evidence of its survival has been found.

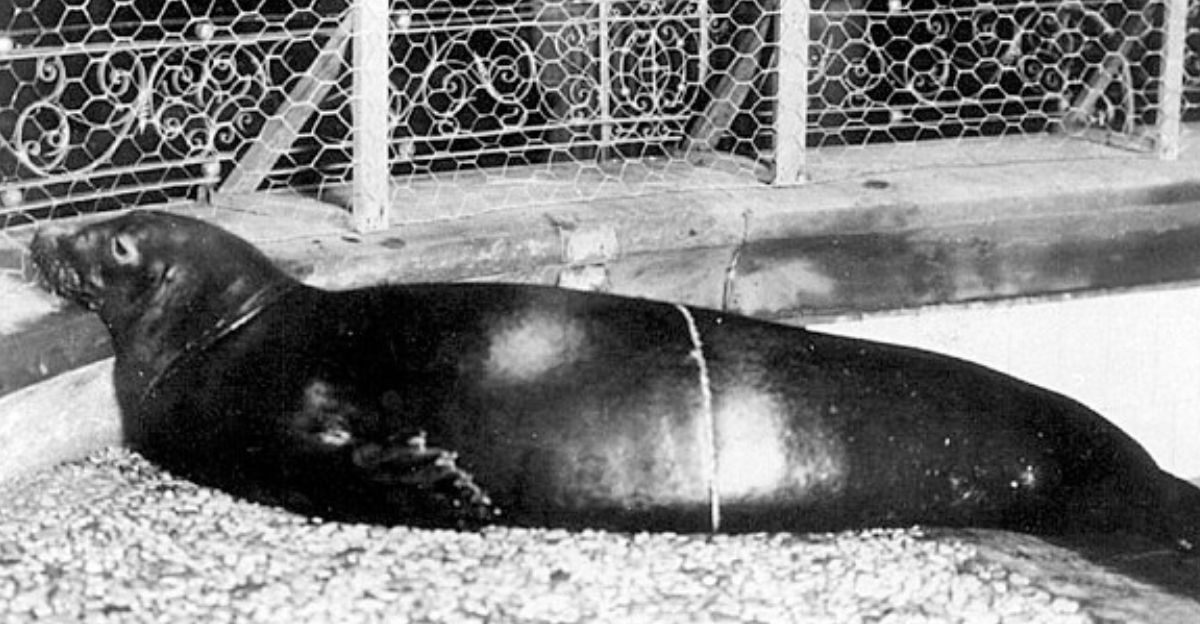

Caribbean Monk Seal (1952)

The Caribbean Monk Seal was declared extinct by NOAA in 2008, marking it the first seal species to vanish due to human activities. The last confirmed sighting occurred in 1952.

Historically found along the beaches of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, these seals faced severe threats from overhunting for oil and meat and overfishing of their prey. According to NOAA biologist Kyle Baker, these factors made the population unsustainable, leading to its extinction.

Great Auk (1844)

The Great Auk’s extinction is well-documented, with the last breeding pair killed on July 3, 1844, by fishermen on Iceland’s Eldey Island, which also destroyed their only egg. Known as the “penguins of the North Atlantic,” these flightless seabirds stood about three feet tall.

Demand for their specimens from museums significantly contributed to their decline, as collectors paid high prices for skins and eggs. The final pair was specifically hunted for sale to a merchant, illustrating the harmful effects of human greed and scientific collecting.

Passenger Pigeon (1914)

Once numbering in the billions, Passenger Pigeons formed vast flocks that darkened skies for hours. The last individual, Martha, died at Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914, marking the end of perhaps North America’s most abundant bird.

Commercial hunting drove their extinction, with Wisconsin hosting the largest known nesting site in the late 1800s. Their social breeding behavior, which required large flocks for successful reproduction, made them particularly vulnerable once populations declined below critical thresholds.

Quagga (1883)

The Quagga, a subspecies of Plains Zebra native to South Africa, went extinct in the late 19th century due to excessive hunting. These unique animals looked like zebras and horse hybrids, with stripes only on their front half.

Scientists attempt to “resurrect” the Quagga by selective breeding of zebras carrying quagga genes. This de-extinction project has shown promising results, with several foals displaying quagga-like characteristics, offering hope for genetic resurrection.

Pyrenean Ibex (2000)

The Pyrenean Ibex officially went extinct in 2000, but briefly returned in 2009 when scientists successfully cloned a female using preserved DNA. The clone survived birth but died minutes later from lung defects, making it the first species to go extinct twice.

Extensive 19th-century hunting eliminated this mountain goat subspecies from Spain’s Pyrenees Mountains. Their temporary resurrection through cloning technology demonstrates genetic de-extinction efforts’ potential and current limitations.

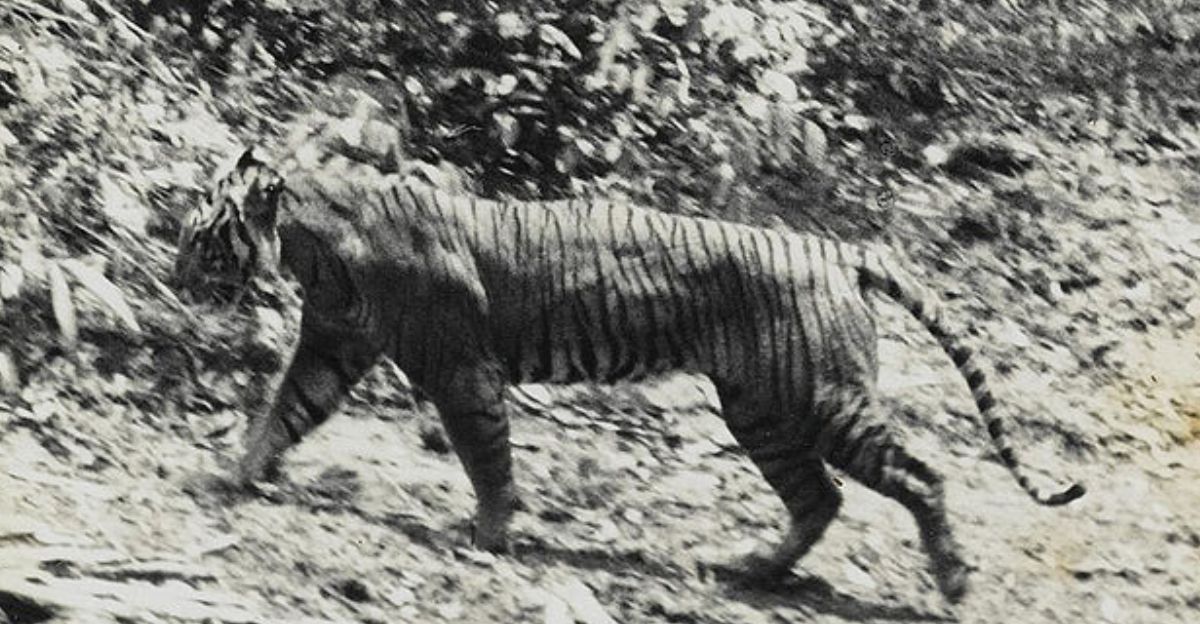

Javan Tiger (1979)

The Javan Tiger was declared extinct in 2008 after the last confirmed sighting in 1976, though some evidence suggests survival until 1979. Habitat loss and hunting on densely populated Java Island drove this Indonesian subspecies to extinction.

Recent DNA analysis of hair found in 2019 has sparked speculation about possible survival, prompting renewed search efforts. However, decades of fruitless expeditions and habitat destruction make rediscovery unlikely, despite local sighting reports.

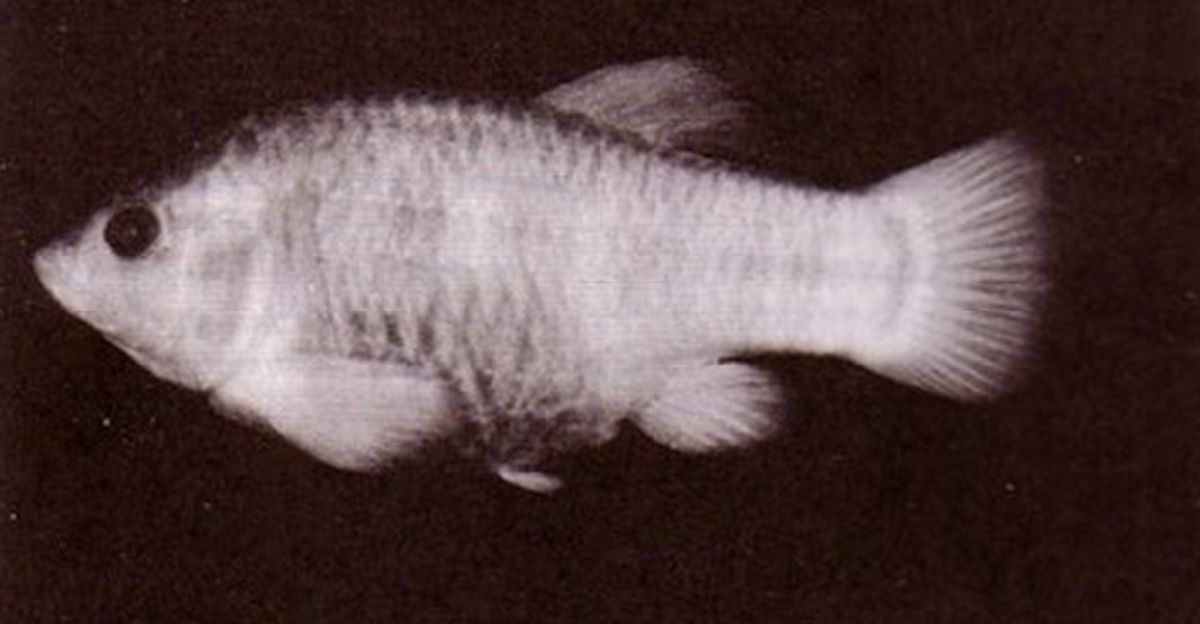

Tecopa Pupfish (1981)

The tiny Tecopa Pupfish became the first species removed from the Endangered Species Act due to extinction in 1981. These heat-tolerant fish lived exclusively in California’s Mojave Desert hot springs, surviving in water temperatures exceeding 100°F.

The development of hot springs for tourism in the 1950s-60s proved fatal, as construction joined northern and southern spring outflows, creating water temperatures that were too hot even for these desert specialists. Hybridization with introduced species completed their demise.

Dodo (1681)

The Dodo of Mauritius became extinct around 1681, though the exact date remains debated among scientists. These flightless birds evolved without natural predators, making them fearless and vulnerable when humans arrived with introduced animals.

Contrary to popular belief, direct hunting wasn’t the primary cause of extinction. Instead, introduced pigs, monkeys, and rats devastated their ground nests, while habitat destruction eliminated their forest homes, creating an ecological catastrophe they couldn’t recover from.

Who’s Next – Vaquita (Less than 10 remain)

The Vaquita porpoise faces imminent extinction with fewer than 10 individuals surviving in Mexico’s Gulf of California. These smallest marine mammals are accidentally killed in gillnets used for illegal fishing, particularly targeting the totoaba fish.

Despite international conservation efforts, their population has crashed by 99% since the 1990s. Marine biologists warn that without immediate action to eliminate gillnet fishing, the vaquita will become the second cetacean species driven extinct by humans within decades.

Kākāpō (238 remain)

The Kākāpō, the world’s only flightless parrot, clings to survival. Just 238 individuals remain on three predator-free New Zealand islands. These nocturnal birds evolved without mammalian predators, making them defenseless against introduced species.

Intensive management has slowly increased its numbers from a low of 51 in 1995. However, genetic bottlenecks, low breeding rates, and vulnerability to disease keep them precariously close to extinction despite heroic conservation efforts.

Sumatran Elephant (Under 2,800 remain)

If current trends continue, Sumatran Elephants face extinction within 30 years. Their population estimates range from 924 to 1,359 individuals, a 52-62% decline since 2007. Rapid deforestation for palm oil plantations has destroyed 70% of their habitat.

The IUCN upgraded its status to “critically endangered” in 2011 after losing nearly 70% of its habitat in just 25 years. Human-elephant conflicts increase as desperate animals raid crops, often resulting in retaliatory killings that further threaten this magnificent Asian elephant subspecies.