A young cashier stares at a handwritten note, turning it sideways as a Boomer customer waits. The words are clear, the cursive looping steadily across the page—but she can’t read it. Around them, the line slows. A simple interaction becomes a freeze-frame of a larger shift: tens of millions of younger Americans confronting skills their parents used daily.

What other everyday abilities disappeared almost overnight—and why?

10. Reading Paper Maps

Before Google Maps launched in 2005, navigation required spatial reasoning, directional awareness, and the ability to visualize terrain from a flat page. Boomers mastered this instinctively. Younger generations, highly smartphone-dependent, often feel helpless without GPS.

Map reading built mental rotation, estimation, and geographic intuition—skills research links to stronger cognitive resilience. When digital navigation fails, Boomers can still orient themselves. Many under 40 simply can’t, illustrating how convenience can erase competence.

Why Map Literacy Matters

Map reading wasn’t just practical—it trained the brain to create mental models of the physical world. Studies on spatial cognition show active navigation forms stronger neural pathways than passive GPS following. Boomers learned to track landmarks, gauge distance, and anticipate turns.

These experiences built confidence in unfamiliar environments. Today, digital-native adults outsource all those functions to their phones, weakening the spatial memory systems humans relied on for millennia.

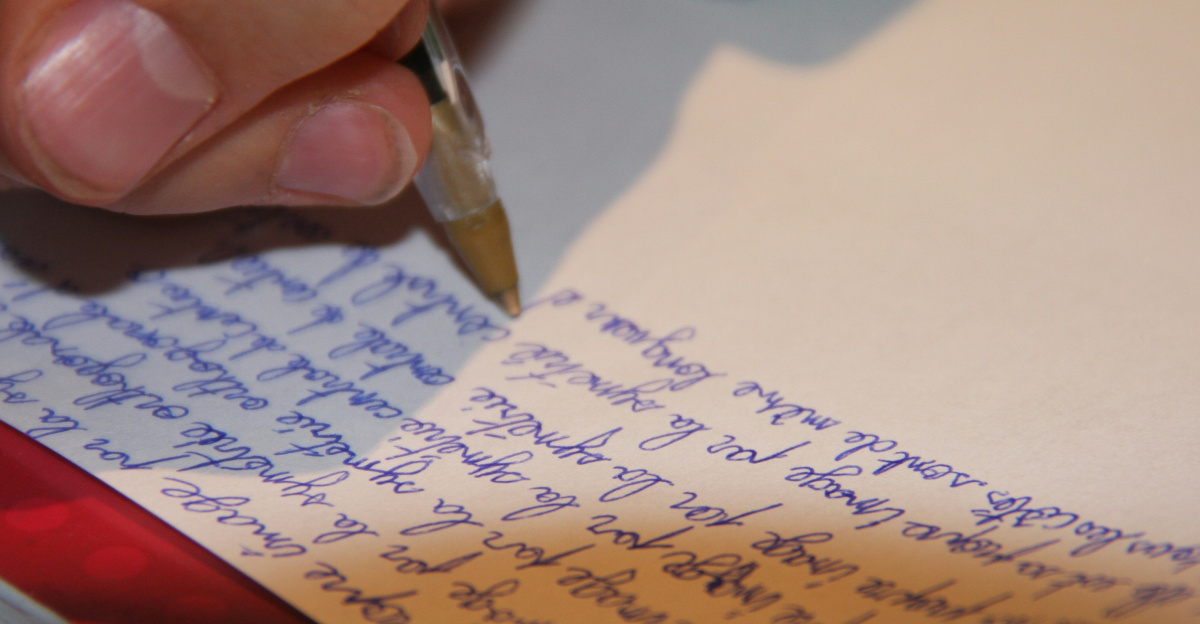

9. Writing Cursive

Cursive was taught universally until around 2010, when 41 states made it optional or removed it entirely. Younger people now struggle both to write and read cursive—losing access to letters, journals, and historical documents. More importantly, handwriting activates brain regions linked to memory, focus, and learning. Research on handwriting shows it strengthens cognitive encoding and fine motor skills far more than typing. Boomers built mental discipline through cursive practice; younger generations bypassed that training entirely.

The Cognitive Power of Handwriting

Research shows handwriting enhances neural activity, fine motor coordination, and deeper information retention. Boomers used handwriting constantly—for school, letters, and record-keeping—reinforcing these benefits daily.

Digital-native generations rely on autocorrect, predictive text, and keyboards, which reduce cognitive load but also weaken the mental processes that reinforce memory. Losing cursive didn’t just change how younger people write—it reshaped how their brains process and store information.

8. Fixing Household Problems

Boomers grew up repairing things: tightening screws, patching drywall, replacing fuses, or fixing a jammed toaster with a butter knife. This hands-on approach created a baseline expectation of self-reliance. Younger adults often default to replacements or professionals.

Without regular problem-solving practice, mechanical intuition fades. Boomers’ DIY mindset preserved competence, confidence, and resourcefulness. The loss of this instinct represents a deeper dependency on service economies and disposable consumer culture.

The Psychology of DIY

A Boomer’s ability to fix common issues wasn’t magic—it was habituated exposure. Repeated small repairs trained causal reasoning and manual skill. Today’s sealed, digital devices offer no such opportunities. As products become more complex and less repairable, younger people lose the chance to develop practical ingenuity. This shift may help explain why younger workers struggle more when systems break down: they didn’t grow up practicing troubleshooting in low-stakes environments.

7. Balancing a Checkbook

Before online banking, every transaction required manual accounting. Balancing a checkbook taught basic arithmetic, delayed gratification, and financial awareness.

Boomers learned exactly how money flowed in and out because they tracked it themselves. Digital banking removed that hands-on feedback loop. Younger generations, though technologically fluent, often lack foundational financial literacy—not because they’re careless, but because the analog training ground simply disappeared.

The Cost of Losing Manual Accounting

Manual balancing forced attention to detail and personal responsibility—skills many financial experts say are weaker today. Younger adults rely on apps that automate categorization, reminders, and budgeting. Convenience reduces friction but also reduces comprehension.

Without manually reconciling spending, it’s harder to internalize consequences. The analog process that once taught Boomers discipline now survives only as a metaphor.

6. Writing Formal Letters

Boomers learned to write letters that were structured, courteous, and persuasive. They practiced greetings, transitions, tone, and respectful communication.

Younger generations, raised on texting and casual emails, rarely develop polished writing instincts. Formal letter writing built clarity, emotional intelligence, and audience awareness. These skills now appear almost elite—not because they’re complex, but because few people under 40 practiced them consistently.

Why Formal Writing Still Matters

Handwriting research shows deeper cognitive engagement, but formal writing adds something else: rhetorical discipline. Knowing how to structure thoughts clearly is essential for leadership, negotiation, and professional credibility. As communication becomes more compressed—emojis, DMs, rapid-fire chat—many younger adults enter the workforce without this foundation. Boomers weren’t inherently better communicators; they were simply trained in a system that required thoughtfulness.

5. Cooking Without Recipes

Boomers learned to cook through repetition and necessity, not apps. They developed intuitive sense—ratios, textures, and flavors—by feel. Muscle memory, not measurement, guided them. Younger generations cook less frequently and rely heavily on recipes, meal kits, and delivery services. While efficient, this removes the trial-and-error process that builds confidence and improvisational skill. Intuitive cooking is more than a talent—it’s embodied knowledge.

Muscle Memory and Adaptability in the Kitchen

Cooking without instructions trains creativity and problem-solving. When ingredients are missing, Boomers improvise; younger cooks often freeze or order takeout.

Culinary intuition requires exposure—thousands of micro-adjustments over years. As fewer households cook regularly, younger people lose this sensory training. The result: more dependence on packaged solutions and less comfort with experimentation.

4. Calling Instead of Texting

Boomers grew up relying on voice communication. Younger generations overwhelmingly prefer texting, which feels safer and more controlled. Yet APA research shows phone conversations build more trust and human connection than written exchanges.

Voice requires real-time listening, emotional attunement, and vulnerability. These are skills that weaken when avoided. Boomers developed conversational confidence because they had no alternative.

The Social Cost of Avoiding Calls

Texting eliminates awkward pauses and spontaneity. It also eliminates tone, empathy, and presence. Younger adults often feel anxious making phone calls—not due to incompetence, but lack of practice. As communication becomes more asynchronous, interpersonal mastery declines. Boomers’ comfort with calls remains a relational advantage in workplaces and families alike.

3. Mental Math

Before smartphones, mental arithmetic was part of daily life: calculating tips, splitting bills, estimating totals. Boomers practiced constantly. Today, calculators live in everyone’s pocket, and mental math is fading fast.

Numerical fluency sharpens working memory and pattern recognition—skills crucial far beyond math. Reliance on digital tools weakens these cognitive pathways, creating a subtle but real decline in everyday problem-solving ability.

What Happens When We Outsource Calculation

Working memory improves through use. When younger generations offload every calculation to a device, that exercise vanishes. Experts warn this contributes to declining number sense—the instinctive feel for quantities, proportions, and trade-offs. It isn’t that younger adults are “bad at math”; their brains simply receive fewer reps. Boomers got those reps daily.

2. Sewing and Mending Clothes

Sewing a button, patching a tear, or hemming pants were once universal skills. Boomers learned them out of necessity. Today, fast fashion makes replacement cheaper than repair, and younger people rarely sew at all.

Yet sewing builds fine motor skills, patience, and practical confidence. It also reinforces sustainability values long before sustainability was a trend.

The Self-Reliance Behind Mending

To sew is to understand how things are constructed. Repairing clothing instills a sense of agency: objects aren’t disposable by default.

Younger people often lack this framework because the economics of fashion—and the availability of tutorials—shifted behavior. But the environmental and cognitive benefits of mending remain significant. Boomers developed them simply by living in a pre-disposable culture.

Waiting Without Digital Stimulation

Perhaps the most overlooked skill: tolerating boredom. Boomers grew up without constant entertainment, and idle moments nurtured creativity, observation, and emotional regulation.

Younger people reach for their phones within seconds. Neuroscientists note that unstimulated time triggers the brain’s “default mode network,” essential for imagination and memory consolidation. Losing boredom tolerance may be the most consequential cognitive shift of all. In a world of endless scrolling, Boomers’ quiet patience has become a superpower.

Sources

Kumar, Amit and Nicholas Epley. “The Underestimated Warmth of Voice.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, vol. 150, no. 10, 2021, pp. 2348-2362.

Mueller, Princeston A. and Daniel M. Oppenheimer. “The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking.” Psychological Science, vol. 25, no. 6, 2014, pp. 1159-1168.

Nakajima, Reiji, et al. “Advantage of Handwriting Over Typing on Learning Words.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 15, 2021, article 679191.

Verghese, Joe, et al. “Spatial Navigation and Risk of Cognitive Impairment.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia, vol. 13, no. 7, 2017, pp. 750-759.

Wei, Ekaterina X., et al. “Psychometric Tests and Spatial Navigation: Data From the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 11, 2020, article 484.