A fisherman’s casual Facebook post revealed something alarming: spiny water fleas, tiny but destructive invaders, had infiltrated Newfound Lake. Within days, biologists confirmed the discovery — these fast-reproducing crustaceans had silently entered the pristine waters, threatening to unravel the delicate ecosystem.

What seemed like an isolated issue turned into a pressing ecological crisis. How did a single image lead to the exposure of a dangerous predator already spreading across the region? Stay tuned as the full extent of the invasion unfolds.

How One Photo Exposed an Invisible Invasion

The discovery wasn’t made in a laboratory; it was made online. A local fisherman’s snapshot led biologists to collect samples that revealed the unmistakable gelatinous tails of the spiny water flea.

This small event uncovered a larger truth — the species had already established colonies. Scientists fear the invasion didn’t just start this year; it likely went undetected for seasons, silently transforming the lake’s ecosystem from beneath the surface.

The Global Origin of a Local Threat

Spiny water fleas first reached North America decades ago in the ballast water of European cargo ships — an ecological Trojan Horse.

Once released, they spread through connected waterways, hitching rides on boats, nets, and fishing lines. From the Great Lakes, they moved eastward into New England. Their arrival in Newfound Lake now signals that even the region’s cleanest, coldest waters are no longer beyond reach.

Why Newfound Lake Was Vulnerable

The conditions were perfect for invasion. Warmer summers, longer seasons, and heavy recreational use created ideal opportunities for contamination.

Fleas can survive for hours on damp gear, easily traveling between lakes. As boat traffic surged across central New Hampshire, each launch ramp became a potential gateway. Climate change accelerated their spread, turning human behavior and environmental shifts into a dangerous alliance favoring the invader.

Tiny Predator, Massive Consequences

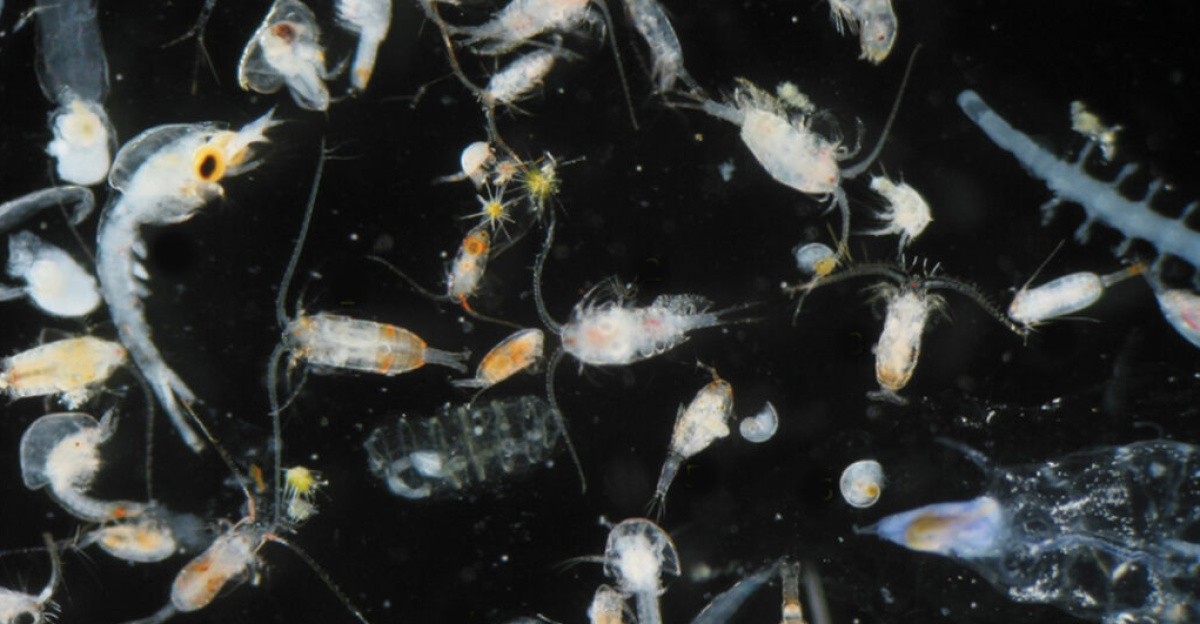

Barely visible to the naked eye, these jelly-like creatures wield sharp spines that puncture fish stomachs. They reproduce exponentially — millions can appear from a single introduction within weeks.

With no known eradication method, scientists warn that once established, they permanently alter freshwater ecosystems. Their life cycle is short, and they reproduce fast. Trying to stop exponential growth is difficult.

The First Victim: Zooplankton Collapse

Spiny water fleas consume the smallest organisms — zooplankton — that form the foundation of lake food webs. Studies from invaded Great Lakes show up to a 50% decline in zooplankton populations, crippling the base of the ecosystem.

Without them, fish larvae and aquatic insects lose their primary food source. The effects cascade upward, shrinking biodiversity and destabilizing species that once kept Newfound Lake balanced.

Fish Populations Next in Line

In lakes where spiny fleas dominate, perch, smelt, and young trout suffer steep population drops. Scientists project 30–40% declines over the next decade if trends mirror other regions.

The youngest fish struggle first — deprived of food, many never reach maturity. It’s a slow collapse that may go unnoticed at first, until anglers realize catches are thinner and favorite fishing spots yield less each season.

Economic Ripple Effects for Local Communities

Newfound Lake’s $50–100 million annual recreation economy depends on fishing, boating, and tourism. As biodiversity erodes, so does the attraction.

Bait shops, marinas, and guides could see gradual losses, not overnight collapse — the kind that creeps year after year. Local families who rely on seasonal visitors may find livelihoods quietly shrinking, as an invisible crustacean transforms economic as well as ecological reality.

From Clear to Cloudy — Tourism at Risk

Once celebrated as the eighth-clearest lake in America, Newfound’s crystalline waters could dull over time.

When spiny fleas remove plankton, algae grows unchecked, clouding the water and fueling oxygen depletion. In similar invasions, like Wisconsin’s Lake Mendota, clarity dropped by nearly a meter. Visitors may not notice right away — until they do, when greenish water replaces the sparkling blue once printed on postcards.

A Hidden Threat to Water Quality

Parts of the region depend on Newfound for drinking water. As blooms increase, so do organic compounds that complicate filtration.

Municipal systems could face higher treatment costs to maintain safety standards. While no harmful algal blooms have yet been detected, the trajectory worries experts. What begins as an ecological story may soon touch human health and municipal budgets across New Hampshire’s lake district.

Property Owners Face Uncertain Futures

For generations, families have cherished Newfound’s shoreline cottages and vacation homes. Yet studies show invasive species can reduce property values when water quality or recreation declines.

Algae-tinted shallows, fewer fish, and murky swimming conditions could make once-prime real estate harder to market. The loss would be measured not only in dollars but in the fading of a cherished lifestyle along the lakefront.

Containment Becomes the New Battle

Experts fear the fleas won’t stay contained. Nearby Squam and Sunapee are now considered high-risk. Because the fleas cling to damp lines and anchors for hours, even a single careless launch can trigger a new outbreak.

Newfound may be only the first domino to fall in what researchers describe as a regional “biological cascade,” where one invasion triggers dozens more across interconnected waterways.

The Growing Cost of Prevention

New Hampshire’s environmental agencies are ramping up boat inspection programs and sampling efforts. Funding now diverts toward public education and monitoring rather than restoration.

Experience from Minnesota and Wisconsin shows that once the fleas appear, prevention budgets balloon, yet eradication remains impossible. Each inspection station or awareness campaign represents the cost of vigilance in a battle that can’t truly be won.

Communities Mobilize

The Newfound Lake Region Association, University of New Hampshire, and the Department of Environmental Services launched joint studies to track population growth and ecosystem changes. Volunteers assist with sampling and shoreline checks, logging every specimen found.

Schools and civic groups now host “Clean-Drain-Dry” workshops, teaching prevention through hands-on demonstrations. A scientific crisis has turned into a grassroots campaign for stewardship.

The Citizen Science Movement

Ordinary residents have become guardians of the lake. Equipped with microscopes and sample jars, volunteers upload data to open databases, helping researchers model spread patterns.

It’s a rare moment where community curiosity aligns with academic need. Each observation builds a map of resilience — proof that the fight for Newfound Lake isn’t only fought in laboratories but along its shores.

Climate Change Makes It Worse

Spiny fleas thrive in warm, stratified water. As summers lengthen and winters shorten, the species gains more reproductive cycles per year.

Scientists now consider the invasion part of a larger climate-linked trend: once-cold northern lakes growing friendlier to warm-water invaders. Each outbreak doubles as evidence that climate shifts don’t only raise temperatures — they rewrite the biology of entire regions.

Why Detection Took So Long

Research from the Great Lakes shows spiny water fleas can lurk at low densities for a decade before populations explode.

They reproduce quickly but remain nearly invisible until conditions align. That means Newfound’s infestation may have begun years earlier. Scientists are now testing sediment cores for dormant eggs, hoping to trace when — and how — the first generation arrived.

Science Accelerates the Response

Universities across New England are deploying DNA-based testing and new sampling tools to catch invasions earlier. Grants now fund research into biological controls, though none have succeeded yet.

What began as a local curiosity has become a case study in ecological rapid response — a living experiment in how science reacts when nature moves faster than bureaucracy.

What Residents Can Still Do

Experts urge simple but strict actions: clean, drain, and dry every boat, trailer, and line; avoid transferring live bait; and let gear air-dry for at least five days.

Even one neglected bucket can transport thousands of dormant eggs. Prevention may sound small, but it’s the only defense left. Every angler and boater who listens becomes part of the containment line.

Lessons From an Unstoppable Invader

From one Facebook post to statewide mobilization, the Newfound Lake invasion reveals how easily ecosystems unravel in the modern era.

Cargo ships, climate change, and weekend recreation together delivered an invisible predator with no cure. The lake’s fate now hinges on awareness and restraint — reminders that once an invader arrives, it never truly leaves. Prevention, not eradication, is the only future worth fighting for.